Transforming Urban Spaces through Landscape Urbanism Interventions

Current social and environmental conditions in the contemporary areas Charles Waldheim in the mid 1990’s coined the term ‘Landscape Urbanism’ which later on became as one of the most literal manifestations of a continuing critical shift to consider open space and natural systems over built form and infrastructure as ways of organizing and planning the city. Waldheim defined Landscape Urbanism as, ‘a disciplinary realignment currently underway in which landscape replaces architecture as the basic building block of contemporary urbanism. For many, across a range of disciplines, landscape has become both the lens through which the contemporary city is rep- resented and the medium through which it is constructed.’ (Paul, 2011).

Landscape urbanism addresses issues of economy, ecology, and the socio-urban context. It is a theory that argues the best way to organize cities is through the city’s landscape and environmental planning. Instead of using the ideas and methodologies of traditional urbanism where designs revolved around roads, buildings, and green spaces were relegated to left-over areas unsuited for building or were used for ornamentation; landscape urbanism offers a fresh perspective for organizing urban form around the cultural and natural processes (Sanghvi, 2020).

Landscape Urbanism & Sustainability – increasing through temporary interventions

Traditional architecture also focuses on the idea of permanence whereas landscape architects and urban designers have a better appreciation towards working in four dimensions and also works with living natural systems that requires an acceptance that is generally not considered as permanent. Whereas a temporary architectural installation is a work designed to last a certain period or to change over time. For example, it can be a single-family home, a piece of micro-architecture, or an art installation. Temporary architectural artefacts are defined by the time they occupy the ground, or when they are adaptable to different uses and users. In the social context, ephemeral architecture could be employed in a variety of scenarios. For example: to accommodate specific events, as a lifestyle choice, as a requirement for a society that reveres change, or as a necessity (emergency architecture).

In the field of landscape architecture, temporary landscapes are an increasingly popular project typology. Pop-up parks, parklets, and temporary art installations have been changing notions of open space. These temporary installations in landscape are defined as that can be easily removed or that changes over with time (Introna, 2021).

Tactical Urbanism – a typology of Landscape Urbanism incorporated by Urban Planners

Tactical Urbanism in modern terminology is known as rapid and low-cost and scalable approach to making temporary changes to the urban environment, often in urban gathering areas. The process combines a development process with social interaction and generally also known as DIY urbanism, Urban Acupuncture, Guerrilla Urbanism, Pop-up Urbanism or Urban prototyping. Tactical Urbanism comprises of five primary characteristics:

1. A deliberate phased approach to instigating change;

2. Local solutions to local planning challenges;

3. A short-term commitment to a longer-term change;

4. Potentially high rewards, low risk; and

5. The building of social capital and organizational capacity between citizens, public and private institutions, and non-profits.

An example of Tactical Urbanism is a temporary tent that was used in many Indian cities during the pandemic to test for Coronavirus. They are inexpensive, easy to implement and provide a short-term solution. Tactical urbanism refers to the development of a variety of approaches and initiatives at different types of properties. Indian cities are embracing this concept during the recent times.

The vacant lands, unorganized storefronts, highway underpasses, parking spaces, urban voids and other unutilized spaces remain highly evident. Tactical urbanism let individuals or government officials use this as experimentation, which often led to innovative creations. The use of tactical urbanism has the potential to inspire progress in place-making. It allows public participation who is the end-users. Citizens can physically feel the alternative option, as they are easy to execute (Thakkar, 2022).

Case Examples:

Main Street Garden Park, Dallas, Texas

Thomas Balsley Associates was selected from an outreach to national and international design firms to design a new park for the Dallas Central District –the first of three called for in its open space master plan as a part of the revitalization strategy. A key component in the downtown revitalization strategy, Main Street Garden Park required the razing of an entire city block of buildings and garages making way for its transformation into a vibrant public space teeming with civic life. This two-acre park is intended to foster downtown residential and commercial growth and is being designed to accommodate the needs of residents in adjacent high-rise residential buildings, university students and faculty, office workers and Main Street shoppers. The design of the park acknowledges the adjacent architecturally significant buildings located within the vicinity such as the Beaux Arts City Hall and Mercantile Bank Building yet strikes a dramatic 21st century design profile at this key location in Dallas’s emerging new urban core. The park includes an open lawn and performance space, a public art installation of light, a green roof civic canopy, seating areas, tot lot, central plaza, a unique urban stream sculptural water feature, a striated garden, an urban dog run, illuminated glass study-room shelters, shade structures and lush plantings throughout. Artful light installations animate the garden room shelters and enhance the Main Street corridor edge throughout the evening. This variety of spaces, ranging from large open lawn and cafe terraces to fountain plazas and garden rooms also host neighbourhood and civic events that bring life and vitality to downtown Dallas (Thomas Balsley Associates).

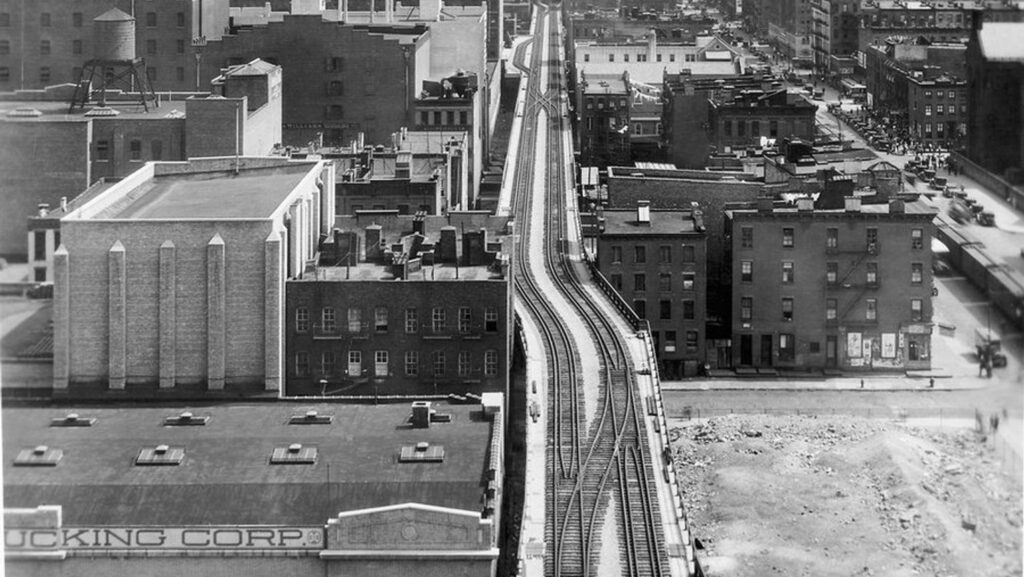

The High Line, New York

The High Line was an abandoned railway line that was converted into a 6.7 acre elevated public park. The project was advocated by the Friends of High-Line the project aimed to provide a green space for the densely packed neighbourhood. The High Line’s design is a collaboration between James Corner Field Operations (Project Lead), Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and Piet Oudolf. The project has linear walkways that blur the boundary between paved and planted surfaces in an elevated level while suggesting evolutions in human use plus plants and birds life. The project soon became a model for reclaiming abandoned urban territories that could be converted into community assets (Sanghvi, 2020).

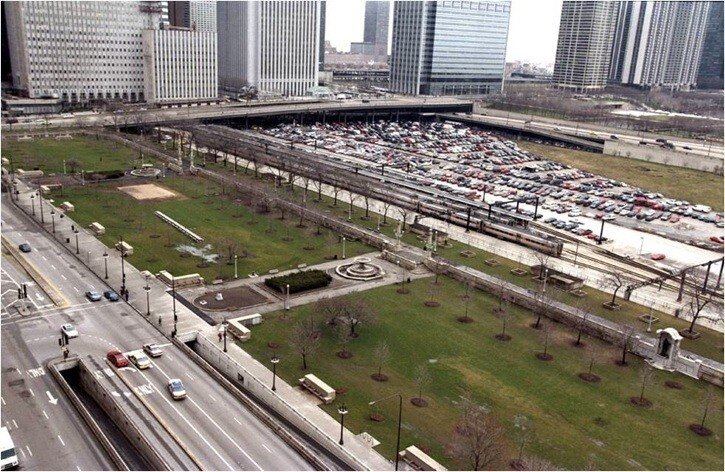

Millennium Park, Chicago

Millennium Park is 24.5 acre public park located between Chicago’s lakefront and the central business district. Between 1852 and 1997, the land that is now Millennium Park was cluttered with parking lots, railroads, and a station operated by the Illinois Central Railroad (Millennium Park).

Opened in 2004, the park includes a diversity of amenities laid out as an extension of Grant Park’s outdoor rooms defined by mature sycamore, honey locust, and maple. At the heart of the park, the Jay Pritzker Pavilion includes a 4,000 seat band shell designed by Frank O. Gehry & Associates. A serpentine pedestrian bridge, also designed by Gehry, connects Millennium Park to Maggie Daley Park. To the south of the Pavilion, the Great Lawn provides flexible space for 7,000 people. Beyond that, the five-acre Lurie Garden, designed by Gustafson Guthrie Nichol and Piet Oudolf, comprises a diverse and evolving collection of thematic plantings inspired by Midwestern eco tones (Millennium Park).

Millennium Park was conceived, designed, and constructed on the idea of creating a free urban, public, and cultural space of uncompromisingly high standards in art, architecture, and design. Beyond its impact within the design and planning fields, the most significant contribution made by Millennium Park is in demonstrating the power of public cultural space to transform tourism, cultural and urban development economies (Millennium Park—The Fortuitous Masterpiece, 2020).

Conclusion:

The goal of landscape urbanism is to design and plan cities that involve ecological, economic and equity sustainability. Ecological sustainability can be achieved by increasing the ecosystem services that can be defined as the benefits we receive from nature: resource, regulatory, support, and cultural services. The social and equity sustainability can be achieved by implementing social equality, where everyone has a right and ease of access to green spaces (Sanghvi, 2020).

Landscape architects and architects must be ready to continuously reinvent themselves as per the conditions, to think in terms of how installations can be reversible and disassembled at the end of the project’s lifecycle. The key could be to move on from the urbanism of grand visions to the urbanism of grand adjustments. The idea should be to design for temporary humans and for temporary functions, to leave a minimal impact and to try to extend the expiration date of the planet for a better sustainable future (Introna, 2021).

References

- Millennium Park—The Fortuitous Masterpiece. (2020). Retrieved from 2020 ASLA Professional Awards: https://www.asla.org/2020awards/899.html

- Introna, M. (2021, 03 04). Increasing Sustainability with Temporary Interventions in the Landscape. Retrieved from Land8: https://land8.com/increasing-sustainability-with-temporary-interventions-in-the-landscape/ Millennium Park. (n.d.). Retrieved from The Cultural Landscape Foundation- connecting people to places: https://www.tclf.org/landscapes/millennium-park

- Paul, R. (2011). Landscape Urbanism. Landscape, April – June, 2011(31), 27-31.

- Sanghvi, A. (2020, 11 15). What architects must know about Landscape Urbanism. Retrieved from Re-Thinking The Future: https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/2020/11/15/a2064-what-architects-must-know-about-landscape-urbanism/#:~:text=Landscape%20urbanism%20addresses%20issues%20of,city’s%20landscape%20and%20environmental%20planning.

- Thakkar, K. (2022, 12 01). An Overview of Tacticle Urbanism. Retrieved from Re-Thinking The Future: https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/2022/01/12/a6052-an-overview-of-tactical-urbanism/

- Thomas Balsley Associates. (n.d.). Main Street Garden Park. Retrieved from Archello: https://archello.com/project/main-street-garden-park

A Comprehensive Guide

Post-Thesis Opportunities & Resources

FREE E-BOOK

Ankur Jyoti Dutta is a landscape architect and academic who completed his master’s degree in landscape architecture from the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi in 2021. He has 3.5 years of experience in both industrial and academic fields, focusing on concepts of nature and culture in the Anthropocene, Cultural Landscapes and their social dimensions, Urban Ecology, Urban Regeneration, Landscape Urbanism, Ecological Urbanism, idea of Sustainability and Energy Efficient Landscapes. He has published articles on Efficient Landscape Design Practices for Universities, Wetlands for Ecological Development in Current Urban Areas, and Threats to Urban Landscape Resources. He currently works as an Assistant Professor (Contract) at the Department of Landscape Architecture at the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “