Book Review: Learning from Las Vegas by Robert Venturi

The 1972 publication Learning from Las Vegas, authored by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, stirred significant controversy, starting with its provocative title. The authors challenged conventional thinking by suggesting that Las Vegas, a city infamous for its indulgence and vice, could offer valuable insights. Rather than focusing on the city’s notorious reputation, the Philadelphia-based architects examined its architectural distinctiveness, questioning how it achieved its success and what makes it unique. Their study presents Las Vegas as a model for architectural communication, emphasizing the lessons its design can impart.

Introduction - Learning from Las Vegas

Learning from Las Vegas is a groundbreaking book in architectural theory, published in 1972 by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour. This influential work challenges the prevailing modernist approach by spotlighting the often-overlooked commercial architecture of the Las Vegas Strip.

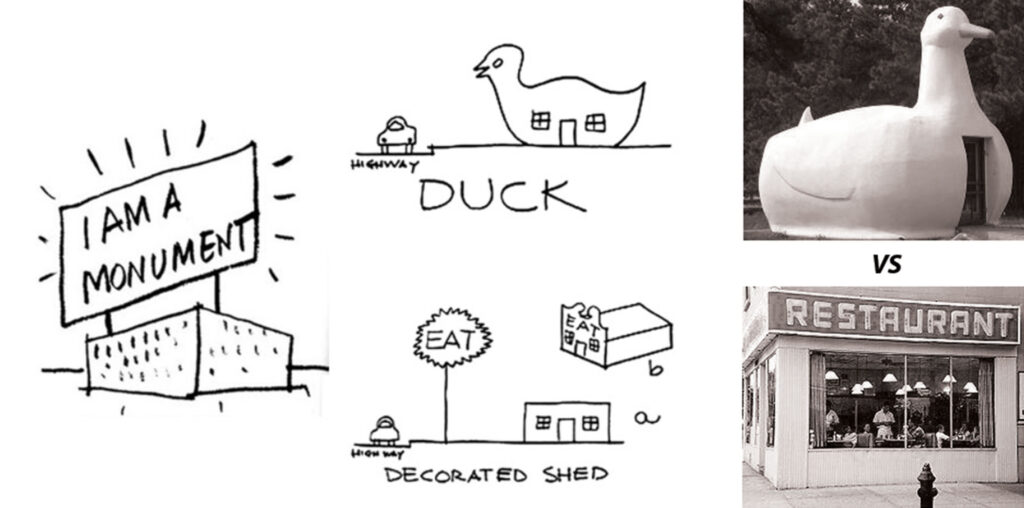

The book is split into two parts. The first part, “A Significance for A&P Parking Lots, or Learning from Las Vegas,” looks at how architecture communicates and symbolizes meaning. They introduce the concepts of the “Duck” and the “Decorated Shed” to describe buildings that either directly express their function through their form or use decoration to convey meaning on a generic structure.

The second part, “Ugly and Ordinary Architecture, or the Decorated Shed” takes a deeper dive into their critique of modernism. It offers for an inclusive approach to architecture that embraces popular and commercial culture. They argue that the built environment should mirror the complexities and contradictions of contemporary life.

Their field research in Las Vegas, including detailed analyses of its signs and spatial organization, underscores that architects must learn to read and incorporate the rich visual and symbolic language of everyday life to create environments that are more engaging, accessible, and meaningful to the public.

Uncovering Architectural Gems: The Significance of A&P Parking Lots

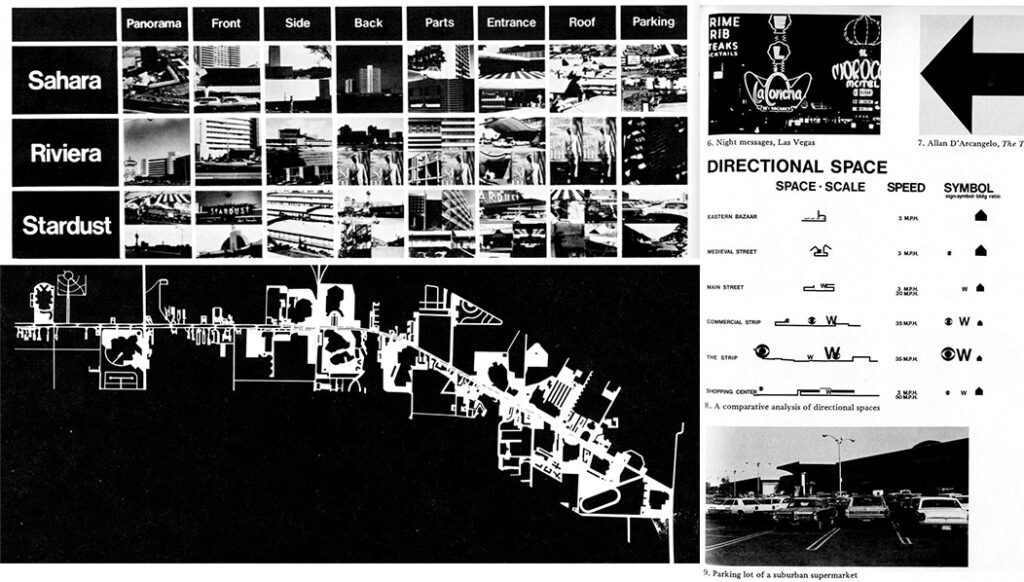

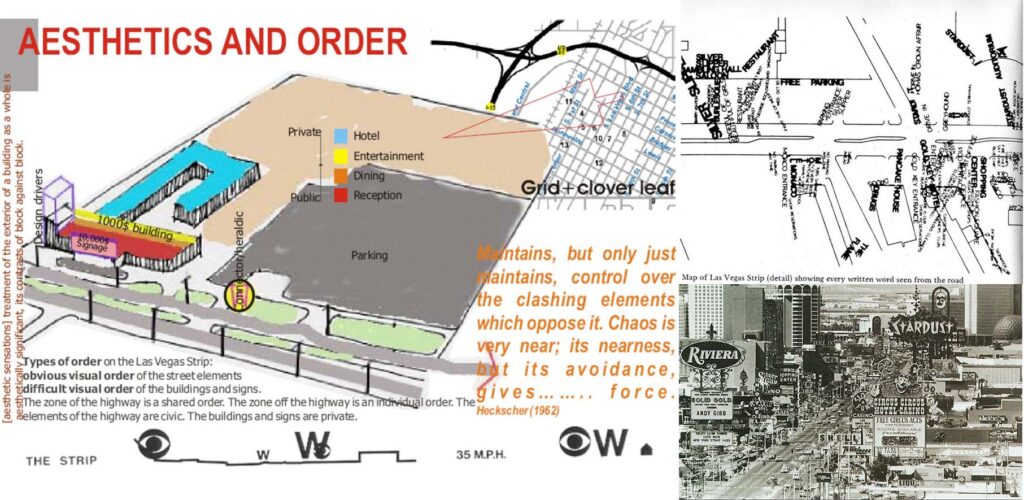

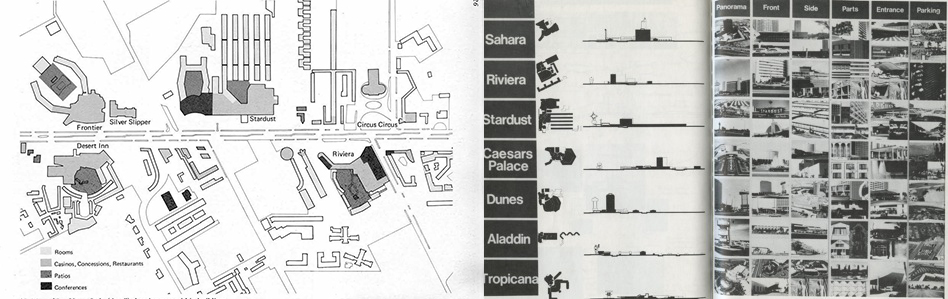

The opening chapter, “A Significance for A&P Parking Lots, or Learning from Las Vegas,” argues for a paradigm shift in architectural analysis, encouraging a respectful and empirical approach to studying existing landscapes. The author emphasizes that places like the Las Vegas Strip, with its dazzling signs & sprawling commercial spaces, offer rich insights into how architecture communicates. These elements are not mere decorations but integral to creating a dynamic and engaging urban experience which contrasts sharply with modernism’s often sterile and utopian ideals. By analysing the spatial organization of A&P parking lots—seen as modern piazzas—they reveal the deep symbolism and practical design considerations inherent in these everyday spaces. The authors argue that the visual chaos of Las Vegas holds lessons for architects about how people interact with their surroundings. They note that the Strip’s structure isn’t immediately obvious and consists of three messaging systems: signs, physical form, and locational expression. These systems create a unique rhythm in the environment, which is often disrupted by privately owned architecture. This perspective embraces the complexities and contradictions of contemporary life, creating designs that are socially relevant and visually engaging.

Source: Website Link

Commercial Values and Methods: Understanding the Strip

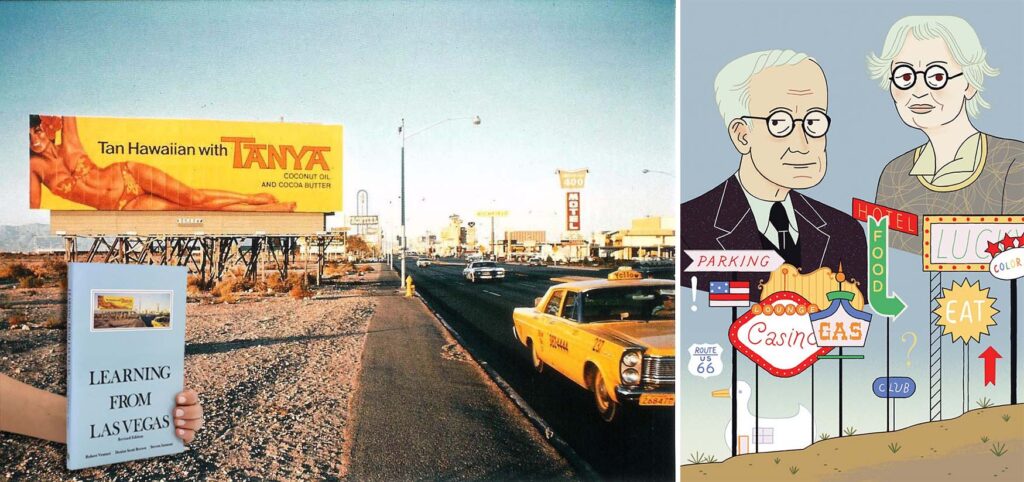

The Las Vegas Strip’s commercial values and design methods highlight the importance of drawing lessons from the existing urban environment. The authors contend that the Strip’s architecture is defined by its prominent use of signage and expansive parking areas, prioritizing visual communication over enclosed spatial design. They challenge conventional architectural principles by asserting that billboards and commercial signs are essential components of the urban fabric, advocating for their inclusion rather than dismissal.

In this context, the Strip’s architecture operates as a communication system tailored to vast landscapes, high-speed environments, and intricate functions, where signage prevails over spatial enclosures. This “antispatial” strategy diverges from traditional approaches centered on defined spaces and subtle design. The authors suggest that by embracing these commercial tactics, architects can become more empathetic and less prescriptive, benefiting both urban regeneration projects and new developments.

Symbol in Space Before Form in Space: Communication Systems in Las Vegas

Las Vegas is a prime example of a city where communication systems dominate the urban experience. In contemporary urban environments, especially those developed with automobile travel in mind, signs and symbols have taken precedence over traditional architectural forms. Here the visual landscape is characterized by bold, attention-grabbing signs that communicate messages over vast spaces.

The authors describe Las Vegas as an “architecture of communication over space,” where the sign for a building is often visible before the building itself. These signs guide visitors, provide information, and create a sense of place even before the physical form of the buildings becomes apparent.

Iconic signs like the “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” and the Stardust Casino sign exemplify how visual elements become central to the city’s identity. The Dunes Hotel’s design, with its grand sign and clear hotel features, blends form and communication, illustrating the integration of architecture and signage. This reliance on visual communication reflects broader urban design trends, where rapid, clear messaging is essential for navigation and experience in high-speed, automobile-centric landscapes.

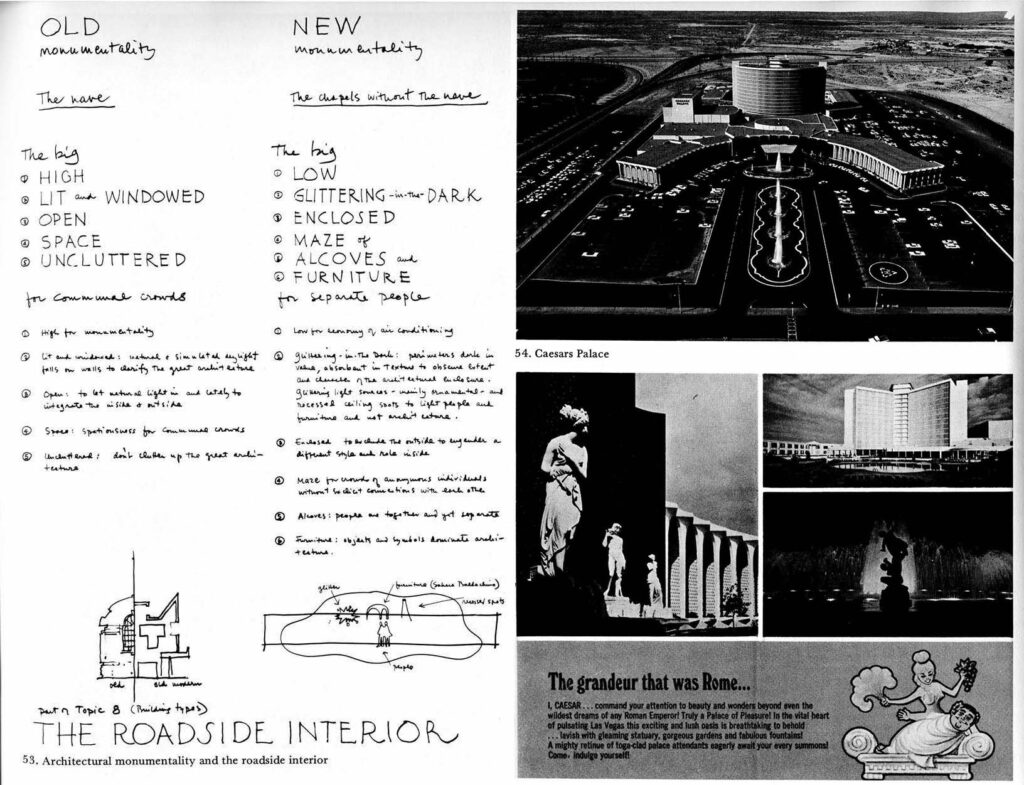

architectural Monumentality: Big Low Space and Its Implications

Monumentality in Architecture refers to the quality of a building or space that conveys a sense of grandeur, significance, and permanence. Traditionally, this has been achieved through the use of large, high spaces .However, in Las Vegas, monumentality takes a different form. Instead of relying on vertical grandeur, Las Vegas casinos utilize big low spaces—large, horizontally expansive interiors with low ceilings. This shift is driven by practical considerations such as budget constraints and air conditioning requirements, which limit the height of spaces

The Las Vegas casino has big low space, with vast, horizontally extended interiors designed for large crowds while maintaining intimacy. Low ceilings, often featuring one-way mirrors, enhance surveillance and cost-effective air conditioning. Functionally, this design disorients visitors, encouraging longer stays and increased spending. Symbolically, big low spaces represent a modern monumentality, focusing on immersive experiences rather than vertical grandeur, and catering to individual activities within a communal setting. Examples like Caesars Palace, The Dunes Hotel, and The Sahara Hotel illustrate how controlled lighting and expansive layouts create a unique architectural monumentality, redefining traditional grandeur and permanence.

Ducks and Decorated Sheds: Decoding the Bold Symbolism of Commercial Architecture

The symbolic roles in architecture is explored here through the concepts of the “Duck” and the “Decorated Shed” which describe the relationship between a building’s form and its function.

The term “Duck” derives from a literal duck-shaped building, the “Long Island Duckling,” a drive-in Junkyard that serves as the primary example of this concept. In the Duck typology, the building itself becomes a symbol, its architectural form representing function or the message it conveys. This approach emphasizes sculptural form over practical considerations, where the structure and program are often secondary to the symbolic shape of the building .

Conversely, the “Decorated Shed” represents a more pragmatic approach, where the architectural form is straightforward and functional, and ornamentation or symbols are applied to the surface. This method separates the building’s functional aspects from its symbolic ones, emphasizing utility and efficiency in the underlying structure, with decoration added to convey meaning.

the Duck’s sculptural form can provide powerful symbolism, it is often less practical and more suited to specific cultural or historical contexts. In contrast, the Decorated Shed offers a flexible and efficient model that can adapt to various functions and contexts while still allowing for symbolic expression through applied decoration.

The Dynamic Duality : Exploring Urban Symphony of Main Street and Strip

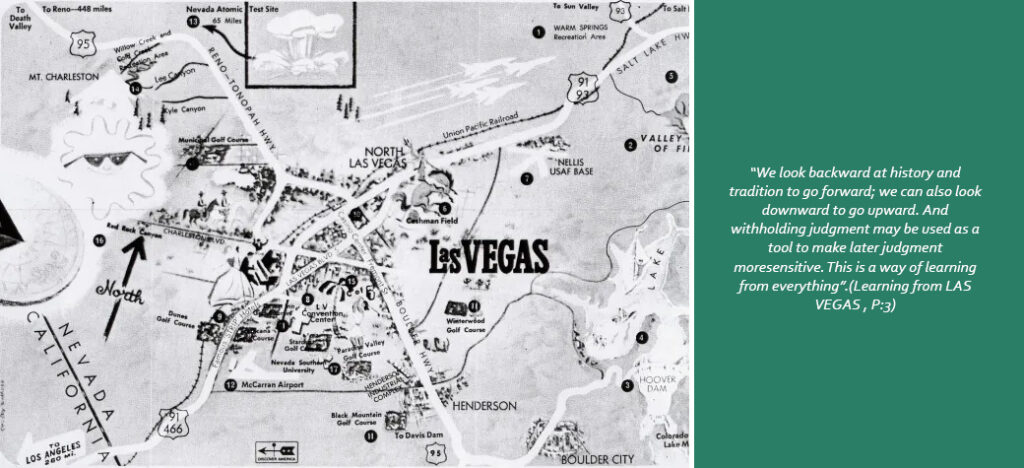

Las Vegas, particularly Fremont Street and the Strip, presents a distinctive urban layout that highlights two contrasting scales of movement: pedestrian-friendly Fremont Street and the automobile-centric Strip.

- Fremont Street, the city’s original main street, features a dense cluster of casinos and a traditional urban setting, with buildings directly engaging the sidewalk, fostering a bazaar-like atmosphere. Once centered around a railroad depot, the street’s historical and symbolic significance endures despite its replacement by other structures.

- In contrast, the Strip caters to vehicular traffic, with wide spaces between buildings and parking areas. While its spatial arrangement may seem disordered, there is an underlying structure governed by the continuous highway and its turns. The Strip’s layout follows a dual order system:

- Civic Order: Elements like streetlights and road signs provide a sense of rhythm and continuity.

Private Order: Diverse building designs and signage contribute to a visually dynamic, competitive landscape. - The interplay of various buildings and activities creates a vibrant and diverse urban fabric, reflecting Las Vegas’s spirit of both individual competition and collective community.

Embracing the Everyday: The Aesthetic Revolution of Ugly and Ordinary Architecture

The origins of the “Ugly and Ordinary” concept rooted from reaction against the Heroic and Original—the modernist architecture which prioritizes innovation, purity, and often an elitist perspective separates architects from the general population. The authors point out that modernism has been more about creating monuments than creating functional and meaningful spaces to the everyday user.

“Ugly” in this context does not necessarily mean visually unappealing but refers to buildings that may not conform to conventional architectural standards. “Ordinary” refers to commonplace structures designed for utility and direct communication, often using common building methods and materials.

Contrasting the “Ugly and Ordinary” are theories—what might be called “Heroic and Original.” This perspective views architecture as an art form that should transcend common tastes and resist commercial influences. It often results in buildings that are celebrated within professional circles but may feel alienating or irrelevant to the general public.

The “Ugly and Ordinary” theory suggests that architects should pay attention to vernacular architecture that people use and enjoy on a daily basis. It calls for a democratization of architecture, where values and tastes of the broader society are considered just as legitimate as those of the architectural elite.

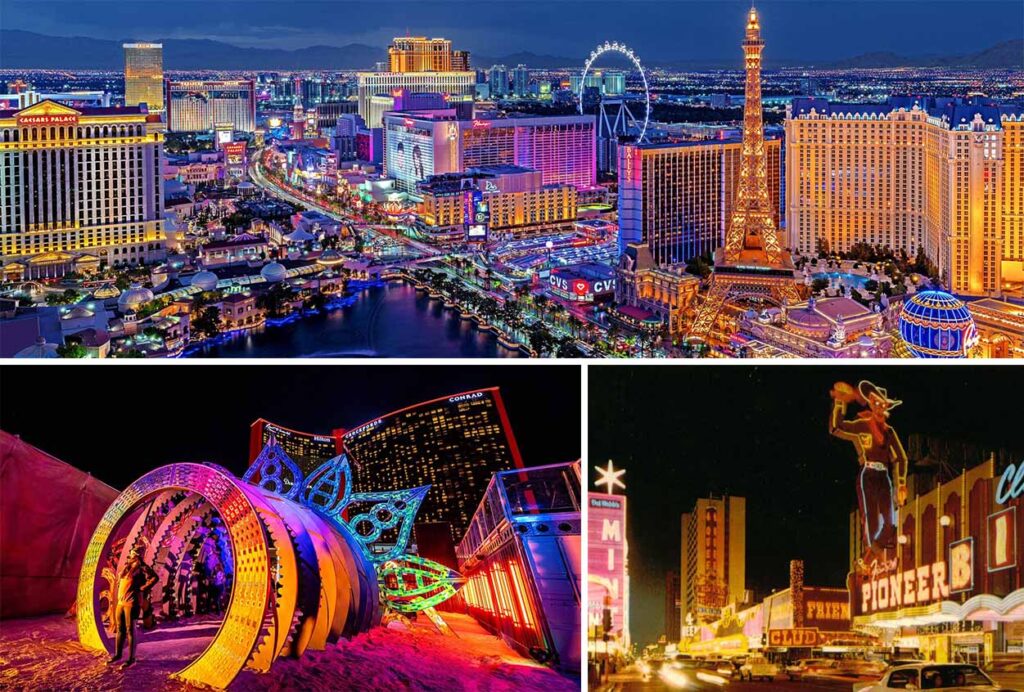

Neon Dreams: The Persuasive Power of Las Vegas Lighting and Signage

The Las Vegas Strip, with its iconic neon lights and bold signage, epitomizes how lighting and signage create persuasive architectural environments. Designed to attract attention, the bright, colorful lights draw visitors from afar, generating excitement and anticipation. Different lighting evoke various emotions:

- Warm, golden lights convey luxury and elegance, while the vibrant, pulsating lights of Fremont Street create an energetic vibe.

- Spotlights and backlighting highlight unique architectural elements, reinforcing brand identity.

Signage serves both informational and persuasive functions. Large, bold signs provide information about attractions, shows, and services, persuading visitors to choose specific venues. Each sign reflects the theme and identity of its venue, such as the retro-style neon sign of the Flamingo Hotel or the futuristic signage of The Cosmopolitan. Iconic signs, like the “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign, have become cultural landmarks, enhancing the city’s visual identity and guiding visitors.

At night, the Strip transforms into a mesmerizing display of lights, creating a captivating urban landscape. Panoramic views, close-ups of iconic structures, and street-level perspectives highlight how lighting and signage enhance the thematic elements and immersive experience. This strategic use of lighting and signage not only attracts visitors but also ensures unforgettable experiences, defining the unique character.

Architectural Iconoclasm: Challenging Modernist Orthodoxy

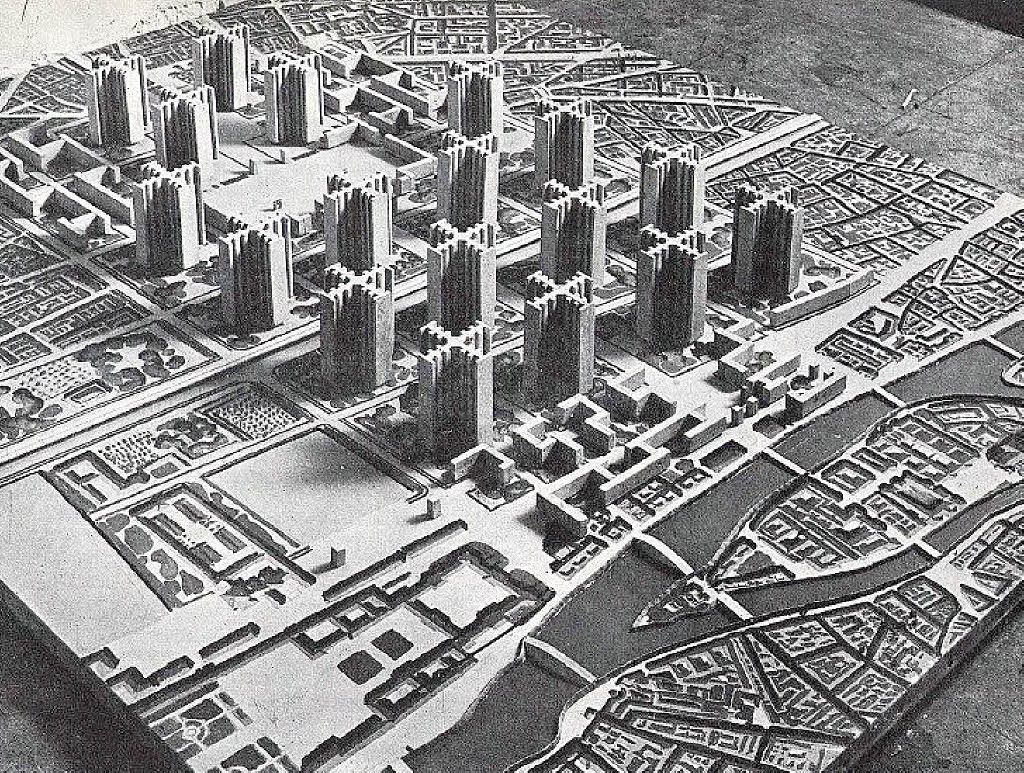

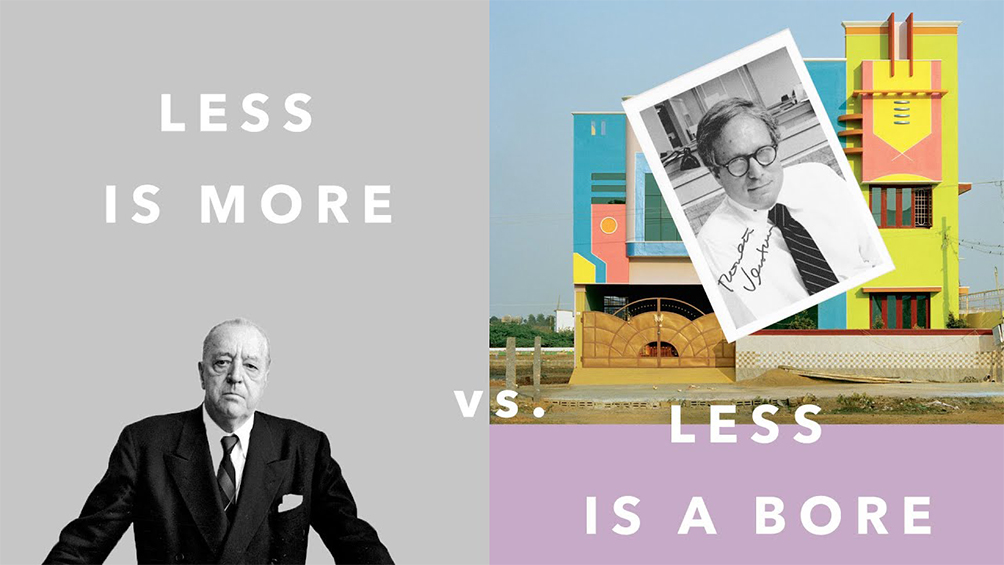

In Learning from Las Vegas, Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour critique modernist architecture for its focus on functionalism and minimalism, exemplified by architects like Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. They argue that modernism neglects the symbolic and cultural dimensions of everyday people. Their critique promotes the concept of the “decorated shed,” where buildings symbolize their function through their decorated exteriors, contrasting with the modernist “duck,” where form dictates function.

Venturi and his colleagues advocate for an inclusive, eclectic approach that embraces historical references and vernacular forms, leading to richer, more communicative architecture. This approach contrasts starkly with modernist principles, emphasizing complexity, contradiction, and the everyday vernacular.

Modernist buildings like Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye and Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building focus on minimal ornamentation and functionalism. Postmodernist buildings like the Vanna Venturi House and Philip Johnson’s AT&T Building incorporate historical elements and decorative features, symbolizing a return to a more human-centric and inclusive architectural dialogue.

This shift towards postmodernism opens the door to a richer architectural discourse, aligning with critiques and proposals by Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour, emphasizing the importance of symbolism and inclusivity in architecture.

Conclusion

Venturi’s playful twist on Mies van der Rohe’s famous aphorism, “less is more,” rephrased as “less is a bore,” encapsulates the book’s central thesis: architecture must engage with the complexities and realities of contemporary urbanism rather than adhere strictly to minimalist aesthetics.

“Learning from Las Vegas” argues for a curious and open-minded anti-utopianism, for understanding cities as they are rather than how planners wish they might be—and then using that knowledge, systematically and patiently won, as the basis for new architecture. — The New Yorker (Niland, J. (2023, January 27). The lessons we’re still ‘Learning from Las Vegas’ after 50 years.)

The authors argue for an architecture of inclusion, one that values and learns from the chaotic, contradictory, and often maligned elements of the built environment, such as the Las Vegas Strip. By observing and analysing the visual communication and iconography of Las Vegas, they propose a shift in the architect’s role—from a creator of new forms to a curator of existing conditions. The book’s blend of theoretical rigor, practical insights, and rich visual content makes it a resource for architects, urban planners, and scholars interested in the cultural dimensions of architecture.

References

1. Venturi, R., Scott Brown, D., & Izenour, S. (1972). Learning from Las Vegas: The forgotten symbolism of architectural form. MIT Press.

2. Niland, J. (2023, January 27). The lessons we’re still ‘Learning from Las Vegas’ after 50 years. Archinect. Retrieved from https://archinect.com/news/article/150337222/the-lessons-we-re-still-learning-from-las-vegas-after-50-years)

3. https://discover.hubpages.com/education/Learning-from-Las-Vegas

4. https://architectureandurbanism.blogspot.com/2010/07/robert-venturi-denise-scott-brown-and.html

5. https://www.archdaily.com/991757/learning-from-las-vegas-revisited

6. https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=4v-l3Uwrwlo&ab_channel=DansLeGris

7. https://www.archdaily.com/991757/learning-from-las-vegas-revisited

8. https://www.archdaily.com/875022/9-weird-and-wonderful-architectural-ducks

9. https://architectureandurbanism.blogspot.com/2010/07/robert-venturi-denise-scott-brown-and.html

Tasnia Shamma

About the Author

Tasnia Tabassum Shamma is an architecture graduate currently pursuing a Master’s in Urban Design at Arizona State University. With experience in construction coordination, she has contributed to LEED-certified projects promoting sustainable development. She has also worked with the visual communication team for the World Bank’s Urban and Coastal Resilience project. She focuses on climate change, built environments, heat mitigation, and urban ecology. Her Study aims to optimize urban design and energy networks for efficient renewable energy use. She seeks to enhance energy stability and contribute to self-sustaining cities.

Related articles

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “