Integrating Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) into Urban Planning Practices

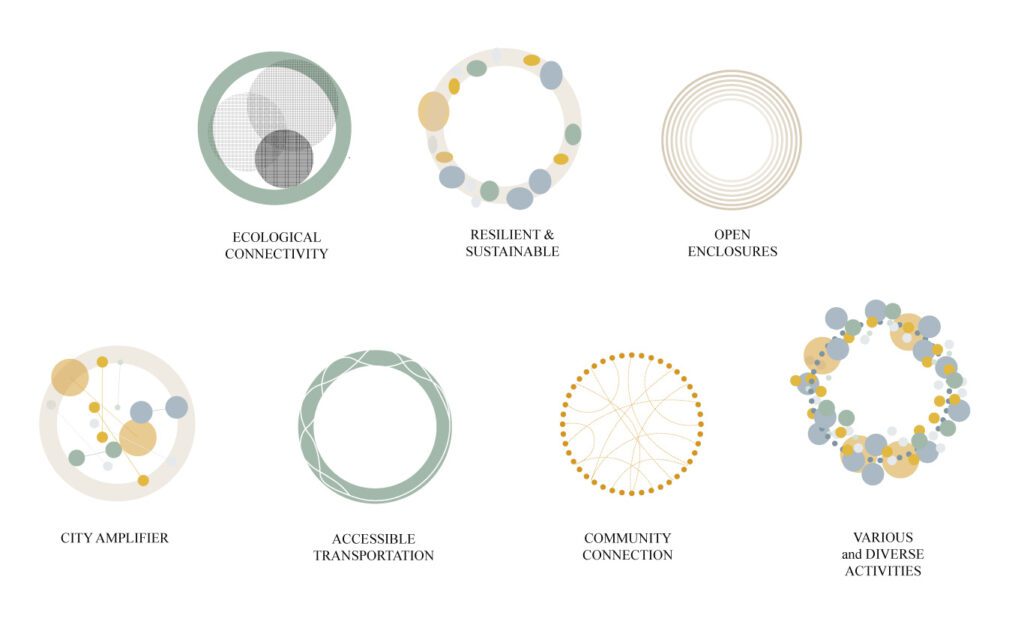

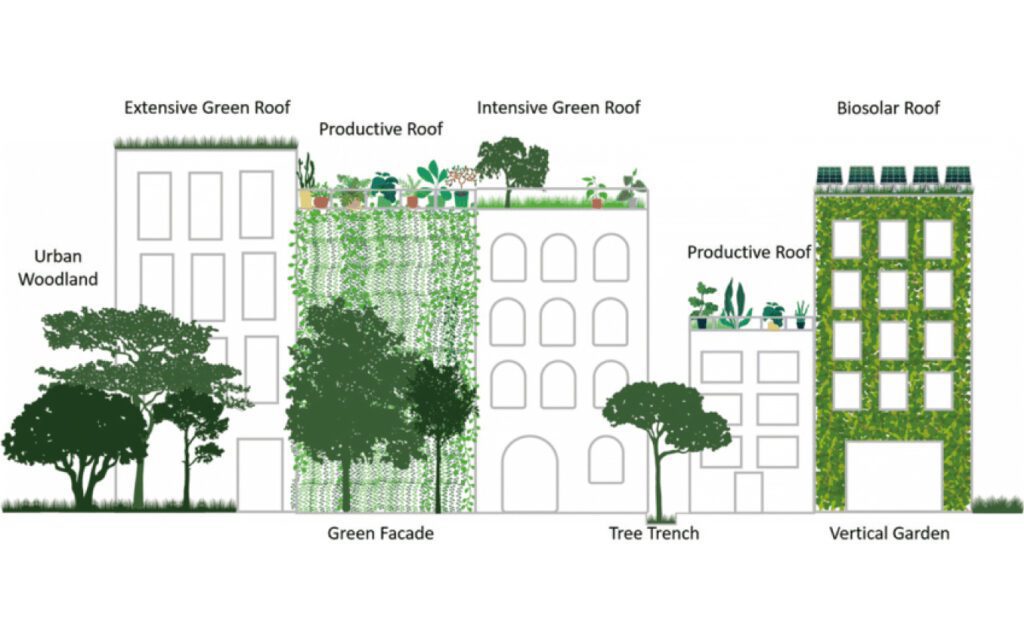

As cities face increasing threats, increasing NBS into urban planning practices offers a promising pathway for creating resilient, sustainable, and livable cities. By incorporating elements such as green roofs, urban wetlands, and biodiversity corridors, cities can enhance ecosystem services that benefit both humans and nature. These solutions not only mitigate environmental hazards but also improve urban biodiversity and offer numerous social and economic co-benefits.

The Benefits of NBS in Urban Contexts

The benefits of integrating NBS into urban contexts are multifaceted, ranging from ecological improvements to social and economic gains. NBS can help cities manage stormwater, reduce urban heat islands, and improve air quality, making urban environments more resilient to climate impacts. Beyond environmental gains, NBS can enhance urban livability by increasing access to green spaces, which in turn promotes physical and mental health. Additionally, they support economic development through increased property values, eco-tourism, and job creation within the green economy sector.

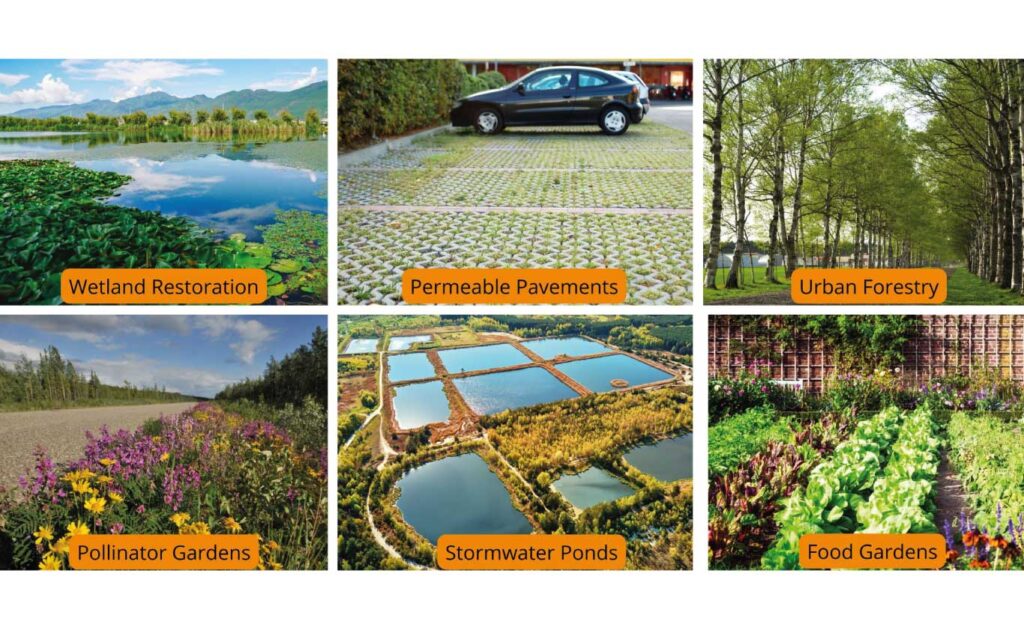

NBS as Climate Adaptation Strategy

Urban areas are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts like flooding, heatwaves, and storms. NBS, as a climate adaptation strategy, offers a natural means of building resilience against these threats. By restoring wetlands, planting trees, and creating green infrastructure, cities can reduce flood risks, lower temperatures, and absorb carbon dioxide. For instance, wetlands act as natural buffers that absorb excess rainfall, while trees and vegetation reduce heat by providing shade and evapotranspiration. These nature-based adaptations are often more cost-effective and sustainable compared to conventional infrastructure like drainage systems and seawalls.

Source: author

Policy and Planning Frameworks for NBS

Integrating NBS into urban planning requires supportive policy frameworks that recognize the value of natural systems in urban development. Policies that prioritize green infrastructure, incentivize biodiversity conservation, and provide funding for NBS projects are crucial for enabling implementation. Planning frameworks should incorporate NBS at all scales, from neighborhood green spaces to city-wide green corridors. For instance, some cities have established “green” building codes that mandate green roofs or permeable pavements in new developments. Such policies ensure that NBS are not just optional amenities but integral components of urban infrastructure.

Source: author

Community Engagement in NBS Implementation

Successful integration of NBS into urban planning requires active community engagement. Community involvement in the design and maintenance of green spaces fosters a sense of ownership and ensures that the solutions meet local needs. Public consultations, workshops, and citizen science projects can enable residents to contribute their insights and help maintain NBS projects over time. By involving communities in decision-making, cities can also promote environmental awareness and encourage sustainable practices among urban residents.

Challenges in Integrating NBS in Urban Planning

Despite the numerous benefits, integrating NBS into urban planning faces several challenges. Limited funding, land scarcity, and competition with traditional gray infrastructure can hinder NBS implementation. Additionally, policymakers and urban planners may lack awareness of NBS benefits, and their impacts may take years to manifest, making it difficult to gain immediate political or public support. Technical expertise and interdisciplinary collaboration are also essential, as implementing NBS often requires knowledge in ecology, hydrology, and landscape architecture.

Source: author

Case Studies of NBS in Urban Planning

Many cities worldwide offer inspiring examples of NBS in urban planning. In Singapore, vertical gardens and rooftop greenery have transformed the cityscape into a lush, biodiverse environment. Similarly, in Rotterdam, the city’s “water plazas” capture and store rainwater to reduce flooding risk. In Copenhagen, the “climate-resilient neighborhood” of Østerbro includes green streets, permeable pavements, and rain gardens that enhance local resilience to storms. These case studies illustrate how cities can creatively adapt NBS to local challenges and conditions.

Integrating NBS in Developing Cities

While NBS are increasingly incorporated into urban planning in developed countries, developing cities often face unique constraints. Rapid urbanization, limited funding, and competing developmental priorities can make it challenging to allocate resources for NBS. However, NBS can be particularly beneficial in developing cities, where they can address urgent needs for flood control, air purification, and shade. Partnerships with international organizations and access to green finance, such as climate funds, can help bridge the resource gap and support NBS implementation in these settings.

The Role of Technology and Innovation

Advancements in technology can enhance the effectiveness of NBS by supporting planning, implementation, and monitoring. Geographic Information Systems (GIS), remote sensing, and environmental modeling can help urban planners identify areas most suitable for NBS and assess their impacts over time. For example, data-driven tools can predict where green roofs will have the greatest cooling effect or where wetlands could reduce flood risks. These technologies ensure that NBS are implemented strategically and allow for the ongoing assessment of their effectiveness in urban settings.

Conclusion

Integrating NBS into urban planning practices presents a transformative opportunity to build more resilient, sustainable, and healthy cities. By adopting NBS, urban areas can simultaneously address environmental, social, and economic challenges, creating a harmonious relationship between nature and urban life. Achieving this integration requires a collaborative approach involving policymakers, urban planners, communities, and private stakeholders. As cities around the world face mounting environmental pressures, NBS offer a promising, adaptable, and impactful strategy for urban resilience and sustainable development.

References

- Anguelovski, I., New Directions in Urban Sustainability and Nature-Based Solutions: Conceptualizing Connections to Justice, Environmental Health, and Well-Being. Cities

- Cohen-Shacham, E., Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

- European Commission. (2015). Towards an EU Research and Innovation Policy Agenda for Nature-Based Solutions and Re-Naturing Cities. Brussels: European Commission

- Frantzeskaki, N., Designing a Knowledge Co-Production Operating Space for Urban Environmental Governance—Lessons from Rotterdam, Netherlands, and Berlin, Germany. Environmental Science & Policy

- Haase, D., A Quantitative Review of Urban Ecosystem Service Assessments: Concepts, Models, and Implementation

- Kabisch, N., Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy, and Practice. Cham: Springer

- Nesshöver, C., The Science, Policy, and Practice of Nature-Based Solutions: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Science of the Total Environment, 579, 1215-1227

- Raymond, C. M., An Impact Evaluation Framework to Support Planning and Evaluation of Nature-Based Solutions Projects

- Silva, C., Nature-Based Solutions for Green Urban Infrastructures and Sustainable Cities: Concepts and Applications. Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2019). Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Manifesto. Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP

Asia Druda

About the author

Asia Druda is a researcher and architect whose work focuses on the intersections of green spaces, health, and landscape planning. Currently publishing in Thesis Publication 2024 with Urban Design Lab.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment

Nature-based solutions, as highlighted by Asia Druda, bring a harmonious blend of innovation and sustainability to urban planning. By leveraging the power of nature, these practices address urban challenges like flooding, heat islands, and air pollution while enhancing biodiversity and community health. Druda’s insights inspire cities to adopt green infrastructure, creating spaces that are not only resilient but also nurturing for both people and the planet.