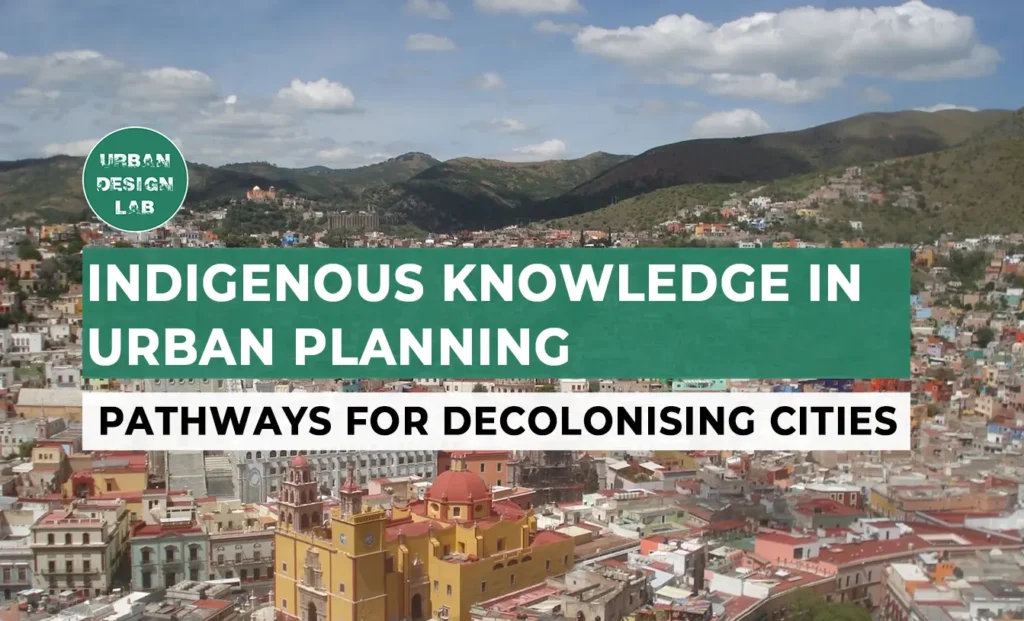

Indigenous Knowledge in Urban Planning: Pathways for Decolonising Cities

Contemporary urban planning continues to bear the imprint of colonial governance structures—characterized by hierarchical, technocratic, and extractive modes of territorial management. These top-down approaches have historically marginalized Indigenous epistemologies, which are embedded in reciprocal, place-based relationships with land, water, and ecology. This article critically examines the potential of Indigenous knowledge systems to reconfigure dominant urban imaginaries toward more equitable, polycentric, and ecologically attuned futures. By displacing the logics of accumulation and control that underpin conventional planning models, architects and urbanists can begin to reframe spatial production through paradigms grounded in traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), intergenerational stewardship, and decentralized governance.

Rethinking Urbanism Through Indigenous Worldviews

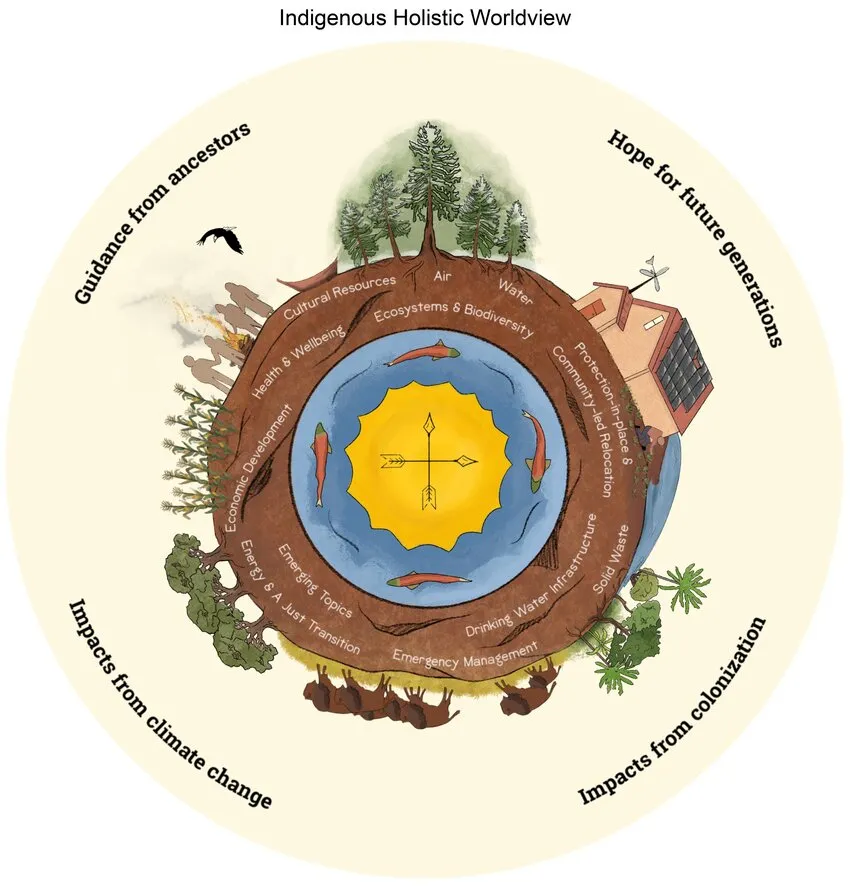

Indigenous ontologies disrupt the Cartesian separation of human and nature that undergirds modernist planning. Land is not a passive substrate for extraction or commodification, but a sentient and sovereign entity embedded within networks of kinship, temporality, and ritual. In Indigenous frameworks—from the Adivasi cosmologies of central India to Māori principles of whakapapa and kaitiakitanga in Aotearoa—urbanism is inseparable from cosmological, ecological, and sociopolitical cycles. These frameworks compel a radical rethinking of core urban planning constructs: density is reframed through seasonal mobility and resource sharing; zoning is reimagined through multifunctional land use rooted in communal logic; and infrastructure is designed with an emphasis on resilience, cultural continuity, and environmental reciprocity.

Crucially, Indigenous-informed planning does not emerge from prescriptive design typologies but from relational authorship—a process of iterative co-creation anchored in listening, adaptability, and collective memory. This shift challenges the dominance of formalist, aesthetics-driven design practices and opens up space for regenerative urbanism that prioritizes multispecies cohabitation, temporal flexibility, and socio-spatial justice.

Reviving Traditional Land Use and Water Management

Indigenous land and water management practices embody sophisticated, site-responsive strategies that predate and often surpass contemporary infrastructural paradigms in both sustainability and resilience. These vernacular systems—stepwells (baolis), sacred groves, seasonal tanks, and rain-fed agroforestry landscapes in the Indian subcontinent—functioned as decentralized ecological infrastructures. Far from being relics of a bygone era, such systems operationalized integrated hydrological planning, microclimatic regulation, and biodiversity conservation through culturally embedded stewardship.

Parallel frameworks can be found across settler-colonial geographies: in Canada, for instance, First Nations communities engaged in watershed-based planning practices that encoded relational ethics with rivers, wetlands, and seasonal cycles, thereby maintaining ecological equilibrium while meeting human subsistence needs.

Reintegrating these land-based knowledge systems into contemporary urban design discourse requires more than symbolic inclusion or technical retrofitting. It demands a paradigm shift—from anthropocentric masterplanning to socio-ecological co-governance. This includes institutionalizing Indigenous sovereignty over land and water, embedding rights-based planning mechanisms, and dismantling legal-institutional barriers that have historically excluded Indigenous actors from urban decision-making processes.

Reviving such epistemologies within the context of climate adaptation and spatial equity not only diversifies infrastructural intelligence but also repositions Indigenous communities from passive stakeholders to sovereign co-authors of the urban future.

Source: Website Link

Design as a Tool for Reconciliation

Architecture, when disentangled from the hegemonic aesthetics of modernism and the logics of erasure, holds the potential to serve as a spatial instrument of reparative justice. In contexts marked by colonial violence and cultural dispossession, the built environment can become a platform for truth-telling, intergenerational healing, and the reclamation of Indigenous identity. Projects such as the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., and the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre in Vancouver exemplify how architectural interventions can shift from representational form-making to ethical place-making—foregrounding Indigenous epistemologies, lived experiences, and cultural narratives.

Such processes disrupt the colonial spatial order by relocating authorship—from elite architects and institutional actors to Indigenous communities themselves. This de-centering repositions design as a relational praxis, rather than a product, allowing for spatial articulation of memory, trauma, and cultural continuity.

Reconciliation through architecture is not achieved through aesthetic tokenism or symbolic gestures; it emerges from sustained co-design processes rooted in participatory ethics, material sovereignty, and cosmological coherence. When local materials, oral histories, and spiritual landscapes inform the design process, architecture transcends its role as static artifact and becomes a living archive—a vessel for remembrance, agency, and rooted futurity.

In this framing, the built environment does not simply represent culture—it enacts it. It becomes a space where the politics of recognition meets the praxis of repair.

Community-Led Development and Knowledge Sovereignty

True decolonisation in urban planning goes beyond symbolic gestures, it involves real structural change. One of the key shifts is giving decision-making power back to Indigenous and local communities, allowing them to shape how cities grow and function. Across the world, grassroots initiatives like participatory mapping, community land trusts, and tribal-led housing schemes are reclaiming space and knowledge. These approaches prioritise lived experience, local wisdom, and self-determination. For architects and planners, this means working alongside communities rather than designing for them.

Cities must embed such participatory practices into policy, education, and institutional frameworks ensuring Indigenous voices are not just consulted, but actively lead the planning process. This is how spatial justice and knowledge sovereignty can take root in the built environment.

A Regenerative Urban Future Rooted in Ancestors

To shape the future of our cities, we must first understand and honour their past.

Decolonising urban spaces is not just about acknowledging historical injustices, it’s about bringing Indigenous values and practices back into everyday planning and design. This means making space for ancestral knowledge and stewardship in how we build, live, and govern. Such approaches encourage cities that are diverse, rooted in place, and resilient by nature. At a time when global challenges feel overwhelming, Indigenous thinking offers clear, grounded guidance for creating ethical, balanced, and life-affirming urban futures. Architecture and planning, when informed by this wisdom, can move beyond sustainability toward regeneration and renewal.

Conclusion

Indigenous knowledge systems are not static cultural artefacts of a pre-modern past; they are dynamic, adaptive epistemologies that continue to shape ways of knowing, dwelling, and relating to land, water, and community. These systems offer a profound counter-narrative to dominant urban paradigms that privilege technocratic rationality, economic efficiency, and spatial abstraction. Rather than conceiving cities as disembedded grids or engines of capital circulation, Indigenous worldviews reimagine the urban as a living assemblage—rooted in reciprocity, memory, and ecological interdependence.

In the face of accelerating planetary crises and widening socio-spatial inequities, the marginalization of Indigenous knowledge is no longer a benign oversight—it is a form of structural erasure. To decolonize urban planning in any meaningful sense, epistemic justice must be operationalized. This requires the systemic integration of Indigenous voices not merely as participants, but as sovereign co-authors in shaping architectural discourse, urban governance, environmental regulation, and pedagogical frameworks.

Decolonisation is not a metaphor—it is a material, institutional, and ideological transformation that challenges whose knowledge counts, whose spatialities are legitimized, and whose futures are rendered possible.

Only through this shift can we begin to construct cities that are not just smart and sustainable in a technocratic sense, but spatially just, culturally resonant, and ontologically inclusive. In this reimagined urban future, the city becomes not a site of extraction and control—but a place of care, relationality, and regenerative possibility.

References

- Porter, L. (2010). Unlearning the colonial cultures of planning. Routledge.

- Jain, A. (2022). Indigenous Urbanism: Lessons from Adivasi Settlements. Journal of Urban Design, 27(1), 44-60.

- Matunga, H. (2013). The Māori of New Zealand. In B. Walker (Ed.), Indigenous Planning (pp. 36–59). McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society.

- Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Duke University Press.

- Shah, N. (2020). Ecologies of Sacred Groves: Urban Lessons from Western Ghats. Landscape Review, 18(2), 88-104.

- Sandercock, L. (2004). Towards Cosmopolis II: Mongrel Cities in the 21st Century. Continuum.

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books.

- Hillier, J. (2007). Stretching Beyond the Horizon: A Multiplanar Theory of Spatial Planning and Governance. Ashgate.

- Tripathi, S. (2019). Water Heritage and Traditional Wisdom in Urban India. India Water Portal.

Neha Lad

About the author

Neha Lad is an urban designer with a global outlook, shaped by her postgraduate journey at the Manchester School of Architecture and hands-on project work across continents. She thrives on connecting bold ideas with on-the-ground realities, weaving research and creativity into every design narrative. Whether sketching city plans or collaborating with diverse teams, Neha brings curiosity and energy to the table believing that great cities are built through both strategy and empathy. Passionate about inclusive urbanism, participatory planning, and ethical innovation, she is committed to shaping urban spaces that are resilient, human-centered, and ready for the challenges of tomorrow.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Best Landscape Architecture Firms in Canada

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “