Anne Hidalgo – aris Transformation & Pedestrian Policy

Anne Hidalgo has been the first female leader of Paris. She does not hail from Paris, nor France for that matter, and as a result has fought an uphill political battle most of her career. However, her progressive, human-centered, and ecologically-conscious politics have shook the City of Light. The city, long struggling with traffic, pollution, and heat, is finally moving toward a more green future. Through the implementation of the 15-minute City concept and equitable economic policies, Hidalgo hopes to set an example for urban leaders on how to put citizens and the environment first.

Paris' New Leader

For much of modern history, Paris has been a world-class destination. It was admired and studied for its unique structure and planning, especially its Grands Boulevards (which would famously inspire Burnham’s Plan of Chicago). Given this prestigious background in the world of urbanism, it should be no surprise the city is once again leading the world through its progressive policy. At the head of this initiative is Mayor Anne Hidalgo, Paris’ first female mayor. Despite significant hurdles and pushback, she has stood strong on progressive housing and environmental policy, making her an example for leaders across the world.

Who is Anne Hidalgo?

But, it was not easy for Hidalgo to reach her current position. In fact, from her early childhood, it seemed the odds were constantly against her. Anne Hidalgo was born June 19, 1959 in Andalusia, Spain, during a significantly turbulent period in the country’s history [1]. Her family background was humble: her father was an electrician and her mother a seamstress [2]. Seeking to escape the political repression of Franco, they fled across the Pyrenees into France, where she was nationalized at age 14.

Due to her culturally-mixed youth, she has expressed feeling more “European” than French or Spanish. Hidalgo has stated she sees her success as a “French version of the American dream” [1]. Not being from Paris– let alone France– her current position and achievements may seem shocking. However, she has publicly alluded to the roots of her determination in her childhood. She recalled publicly: “One day in second grade, my teacher told me: ‘little Spanish girls don’t make it to the top of the class.’ That only made me want to take up the challenge” [2].

Source: Website Link

The Lessons From Her Upbringing

When asked by the LA Times how her background has influenced her mayorship, she responded: “I grew up on a working-class housing estate. It had a bad reputation, which it deserved. The flats were run-down and there were no bathrooms or elevators, but it was a happy Tower of Babel. The neighbors were Armenian, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Russian, North African… The flats on the estates were like rabbit cages that you just wanted to escape from. It taught me a valuable lesson in town planning and social housing” [1].

With her strong desire to prove others wrong, Hidalgo slowly worked her way up in the professional world. For a short period, she was a labour inspector and advisor to labour minister Martine Aubry. Later she became deputy mayor of Paris in 2001, a post she would hold for thirteen years [1]. In 2014, she would run and win the Paris mayorship with 55% of the vote, against the center-right Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) party incumbent, Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet [3].

Mayoral Elections: Battle of the Gendered Words

In a 2014 interview she stated: “My absolute priority is housing, without which all the wonderful opportunities that Paris has to offer its residents means nothing” [1]. She also heavily campaigned on issues related to environmental protection and sustainability– a risky, bold move [4].

In the 2014 mayoral election, gender played a major role in public opinion. Paris had never had a female leader before, so both candidates had to prove their ability to lead the city and tackle serious issues to skeptical audiences. Research found that in her first election, Hidalgo used more masculine-coded language to discuss environmental issues, speaking on economics, technology, etc. After she was able to prove her leadership skills, it is possible she then switched to feminine-coded language, in order to further her objectives as mayor. Topics like conservation, food needs, and solidarity were focused on [4]. These actions show a leader who is willing to take risks, honestly stand on her beliefs, and use her position to positively influence public opinion.

Adoption of the 15-Minute City

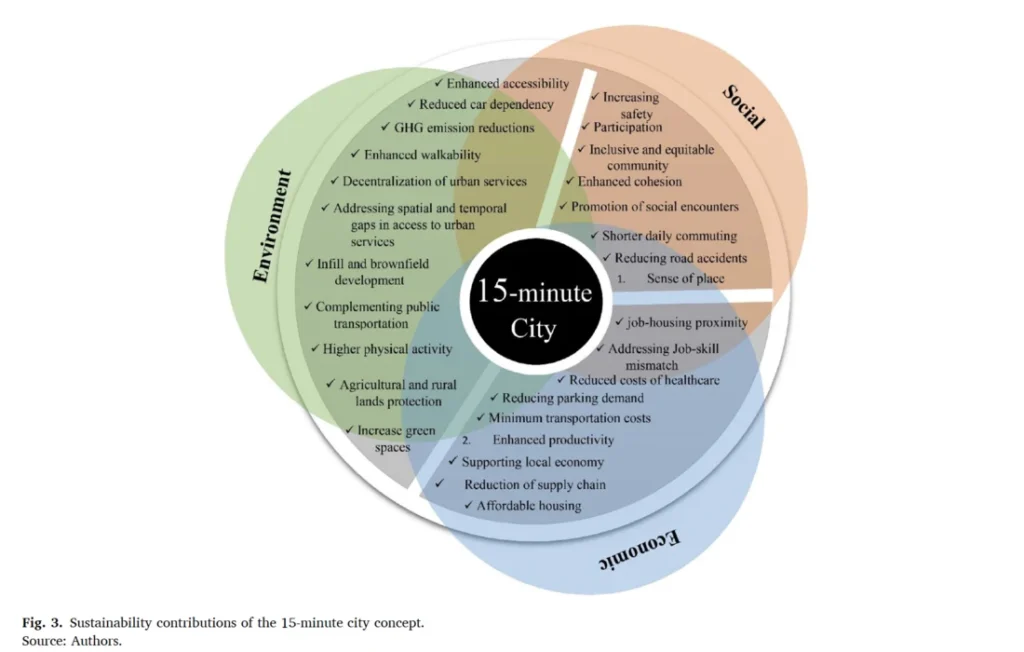

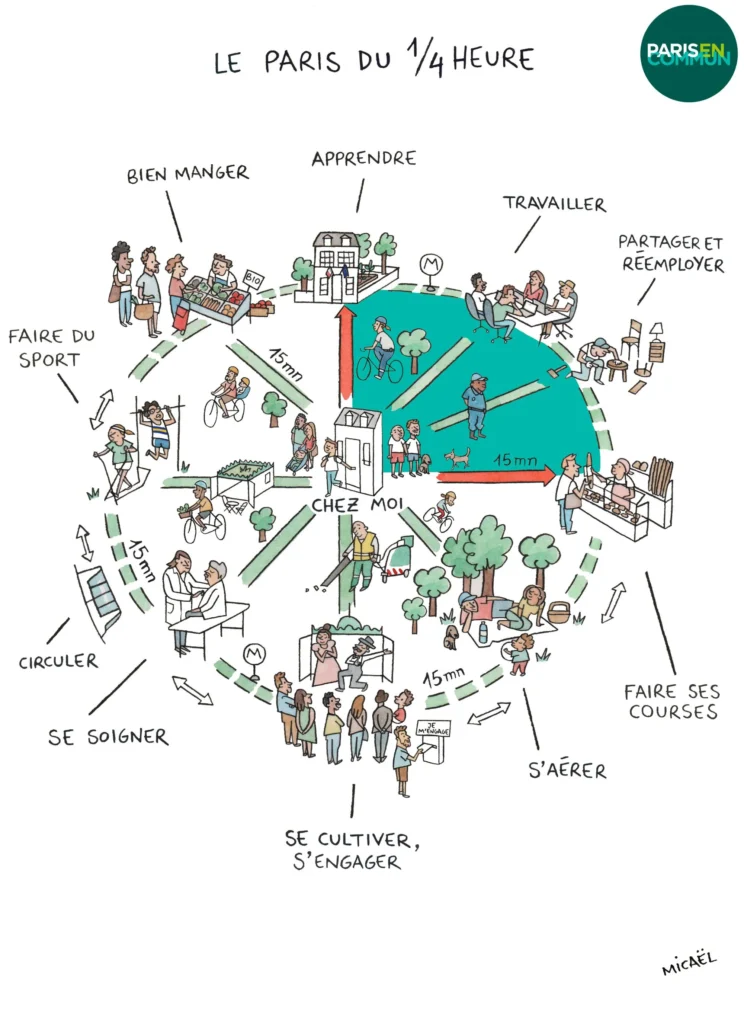

During and after her election, Hidalgo set several goals: accessible housing, ecologically-minded innovation, and solidarity with “vulnerable residents” [1]. Maybe the most prominent expression of practically addressing these goals has been the implementation of the 15-minute City method of planning. The 15-minute City (or 15mC, for short) is a set of human-centered planning goals which urban communities can strive for. The main goal of the 15mC is to allow access (by biking or walking) to any needed amenities (job, school, shopping, recreation, etc.) within a comfortable 15-minute commute [5]. According to the founder of the method, Carlos Moreno, “The 15-minute city is not a magic wand, or a market model — it’s a new urban narrative… It’s a way of shifting the paradigm by basing development on temporal convergence and according to economic, social and environmental priorities, to create livable and equitable cities” [6].

The Seven Habits of Highly Effective Cities

Under Hidalgo, Paris has committed to meet the seven major goals outlined in Moreno’s 15-minute City concept [5]:

-

- Proximity – location of resources for better accessibility to the “six core functions of living, working, commercial, health care, education, and entertainment with a 15-minute walk or bike ride.”

- Density – formation of a “critical mass” which can sustain and foster local business.

- Diversity – fostering both software (social and cultural diversity) and hardware (diversity of types of area uses).

- Digitalization – utilizing up-to-date technologies in order to better serve the citizens of the city; becoming a “smart city.”

- Human scale urban design – prioritize practical human needs and wellbeing rather than traffic and vehicle concerns.

- Connectivity – prevent isolation of neighborhoods and integrate historically disconnected areas.

- Flexibility – more public spaces and multi-use areas; allow single-use buildings to be repurposed or serve multiple purposes throughout the day or week [5].

And these goals are already being implemented. Office spaces are being turned into housing. Car infrastructure is being replaced with bike lanes and public spaces. Local business and circular economic practices are being fostered. At least 5% of the budget is being spent for participatory objectives; over 2,428 projects being initiated since 2014 [7].

The Grand Paris Express

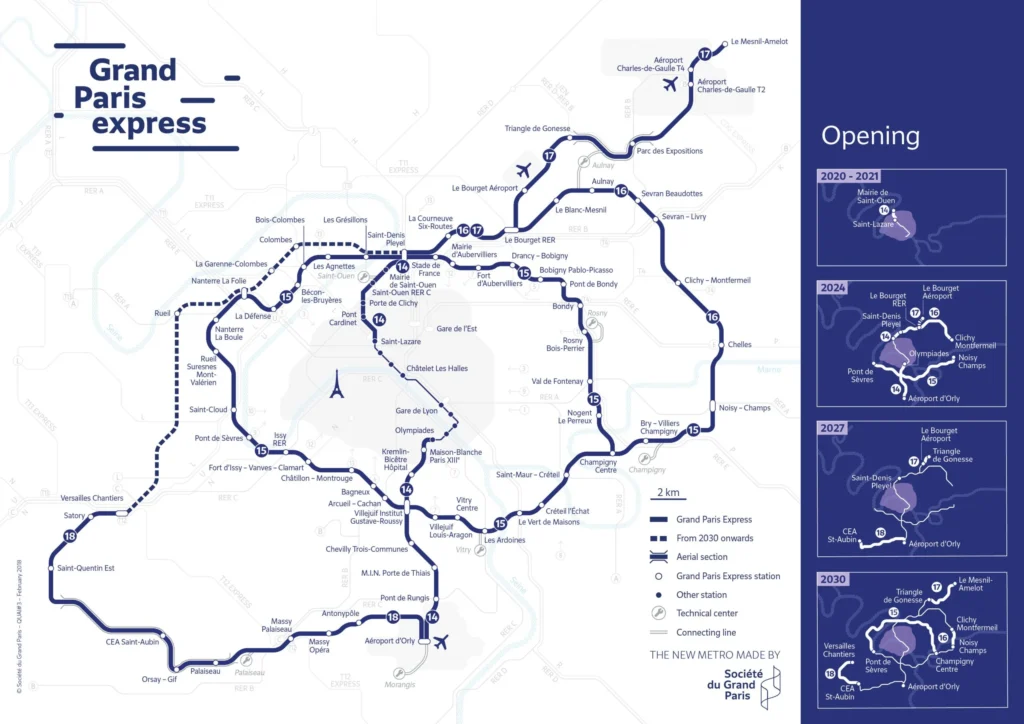

A great example of the lengths Hidalgo has taken to promote a cleaner, more human-centered Paris is through the Grand Paris Express project. It is a major public works plan which sets out to strategically expand the mobility network of the greater Paris metropolitan region past the suburbs, while better utilizing existing urban space. The goals are to reduce sprawl, create locally-focused places, foster sustainable development, and promote social cohesion. Details include 68 new stations and 200 km of new tracks to go around the greater Paris metro area, along with rail-side development hubs which seek to deal with social and environmental issues [8].

One of the major goals of the project is to improve transportation capacities while halving road traffic by 2050. Practical steps include creating another 200 express coach lines; designating special lanes for high-capacity and public vehicles; opening “NewDeal” hubs for multiple transportation types; and providing accessibility to different transport types via a single “Mobility Pass” [8].

Better Living for Greater Paris: New Social and Ecological Environments

Housing, an issue Hidalgo campaigned heavily on, is also addressed in the plans: more social and intermediate housing for low and middle classes are offered; housing market costs will be regulated for first-time-buyers; and mixed social interactions will be promoted through homeshare and student housing initiatives [8].

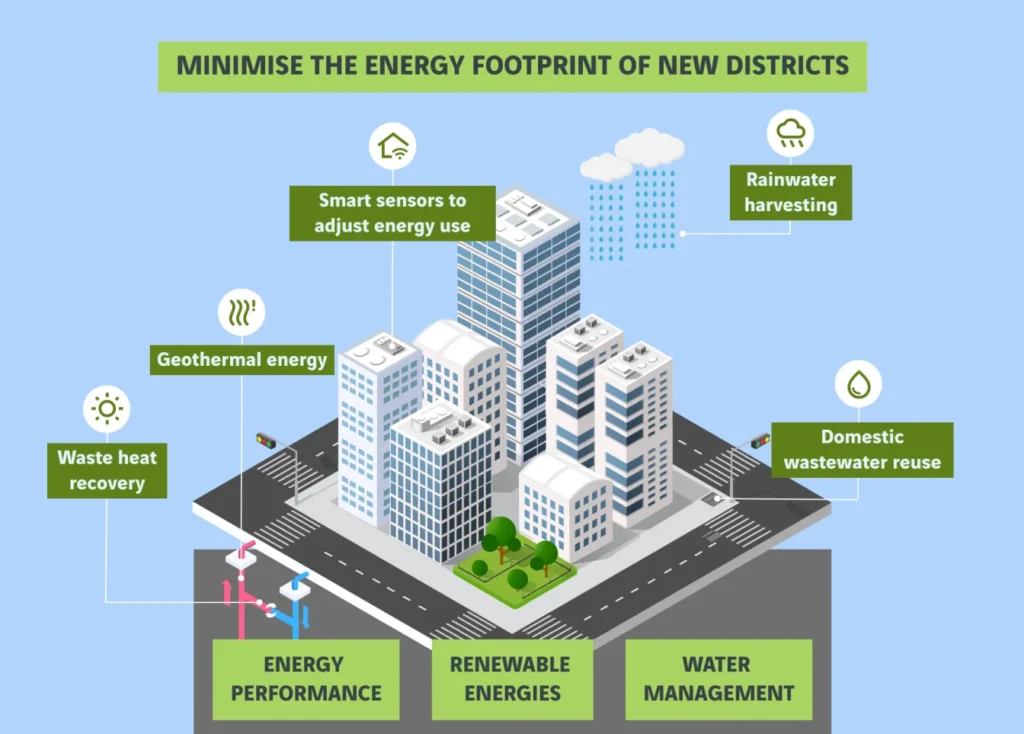

One more noteworthy fulfillment of campaign promises comes in sustainability efforts. Eco-friendly construction methods for projects include implementing low-carbon concrete and recycled worksite material. Using “smart sensors” to adapt buildings’ energy usage to environments has been suggested. Heating networks are planned to be upgraded to operate under geothermal power, and be equipped with waste-heat recovery systems. This will all be along-side new green spaces, permeable surfaces, and wildlife corridors [8].

Case Study of the Place de Catalogne’s “Urban Forest”

Though these plans and practices sound good on paper, you may wonder if there have been any success stories? Well, the success of Hidalgo’s endeavors can be seen now in the revitalization of the Place de Catalogne. The area originally hosted a large, characterless plaza– distinct from the more elegant and homely parts of Paris. Now construction has occurred which is turning portions of the area into an “urban forest.” An article by Bloomburg’s City Lab outlines the project:

“The Place de Catalogne in the city’s south was planted with oaks, ashes, maples and cherries— some saplings, others semi-mature— as a first major action on a commitment to reduce summer heat, increase flood resilience and combat carbon emissions by greening the city. By 2030, Paris hopes to have 50% of its ground area covered by water permeable surfaces, including green roofs, avenues, mini-gardens and new parks, one of which should be open within 12 months” [9].

Plans may reduce the summer heat in the area by as much as 4 degrees celsius, and bike- and green- paths are planned to give better urban and suburban access to Catalogne [9].

Paris Olympics 2024: A Model for Major City Events?

Another case study of Anne Hidalgo’s policies in action has been for the execution of the Paris 2024 Games. To avoid vacant buildings and general wastefulness, the Games were coordinated to make the most out of existing resources. An estimated 95% of the venues used for the Games were already built or were only temporary. Permanent structures were strategically placed in areas of most need: neighborhoods without proper athletics facilities. Much of the equipment was rented, and is being reused by other athletes or sold as souvenirs. Other useful products like pillows and mattresses have been redistributed to community outreach services for vulnerable population needs [10].

Conclusion

Mayor Hidalgo has not been without her detractors. People have criticized the vast amount of projects occurring as turning the city into a construction site, irrespective of residents’ daily needs [2]. And of course there has been the Seine River debacle, where Hidalgo promised to swim in the infamously polluted river ahead of the Paris Games. But these issues of her public perception are not surprising.

Anne Hidalgo has taken great steps forward in the world of human-centered urban policy, especially in a city the size of Paris. She has stood firm and honest in her convictions, and followed through with her claims. Given this strong commitment to positive change, conflict with the public is bound to arise. Regardless of whether one admires or is critical of Paris’ first female mayor, it is undeniable she has started the city onto a more progressive and green future.

References

- https://www.latimes.com/world/europe/la-fg-france-paris-hidalgo-q-a-20140727-story.html

- https://www.france24.com/en/20200629-anne-hidalgo-the-socialist-mayor-of-paris-who-waged-war-against-cars

- https://time.com/43802/5-surprising-things-about-paris-first-female-mayor-anne-hidalgo/

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17524032.2023.2226356

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264275122005406?via%3Dihub

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/27370338

- https://dutpartnership.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/DUT_15-minute-City-Mapping_04-2024.pdf

- https://www.vinci.com/en/emag/greater-paris-inventing-city-future

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-12-08/paris-s-urban-forest-plan-takes-a-new-step-with-trees-at-the-place-de-catalogne

- https://www.olympics.com/ioc/news/paris-2024-games-sports-equipment-and-other-assets-get-a-second-life

Patrick Melo

About the Author

Patrick Melo has a B.A. in Anthropology from Wheaton College (IL). He was a student leader in the International Students Program and is part of the Lambda Alpha National Anthropology Honor Society. He is CITI certified for human research and has conducted two undergraduate ethnographies.

Related articles

Remembering Frank O. Gehry: The Architect Who Redrew Skylines

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “