Decolonizing Urban Design to Reclaim Power in City Spaces

Decolonization politics is a broad and significant topic in architecture and planning. This article analyzes the impact of colonization by looking at examples in India, Venezuela, and Indonesia, with all three ruled by different colonizers. British architecture was merged with the native Indian and Mughal to create a new fusion style called Indo-Saracenic architecture. This fusion is also reflected in Indonesia, where Dutch and native architecture were amalgamated to respond to the climate. The Law of Indies is explored in relation to planning in the country of Venezuela, where towns were mashed together with little regard for local planning to fit the colonial narrative of a country. These examples reveal the deep-trenched nature of colonization in architecture and planning, which is seen even today.

Decolonization is identified as the need of the hour. The article explores how decolonization is carried out on various scales, from street toponymy in Nairobi to city planning in India. It acknowledges how difficult change is and identifies key reasons for this difficulty by studying the case studies. Ultimately, design is identified as the most powerful tool of all, capable of reclamation and celebration of native culture.

Ingrained influence of colonization

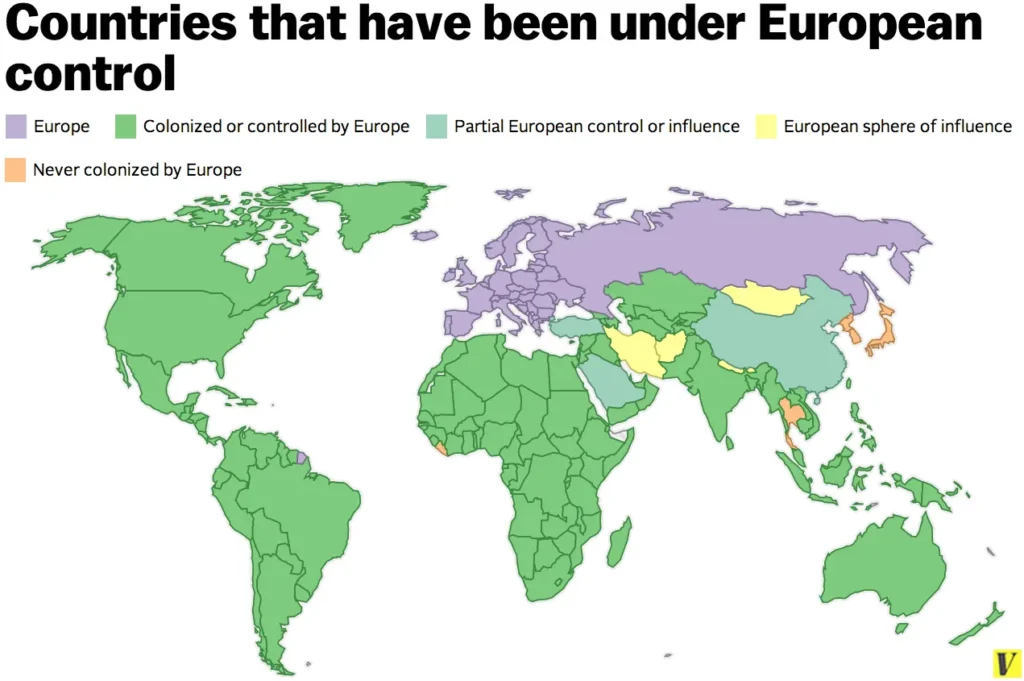

To assume the impact of colonization vanished when the colonies were liberated would be imprudent. Colonizers reshaped the entirety of the country, from urban spaces to local landscaping, to their own liking by erasing the native culture. By deeming their values as superior, they unearthed the existing social foundation to reintroduce a hierarchy that places them at the top and natives at the bottom. The centuries of systematic erasure and control of indigenous people and their culture is not something that can be reversed with a few decades of independence.

With such a deep-rooted belief system, the question of taking back the land and culture is a complex one that demands radical change and often faces resistance. By diving into the extent of colonization on urban design and architecture, designers can work to reverse it and create spaces created for indigenous people by indigenous people.

Colonial city making

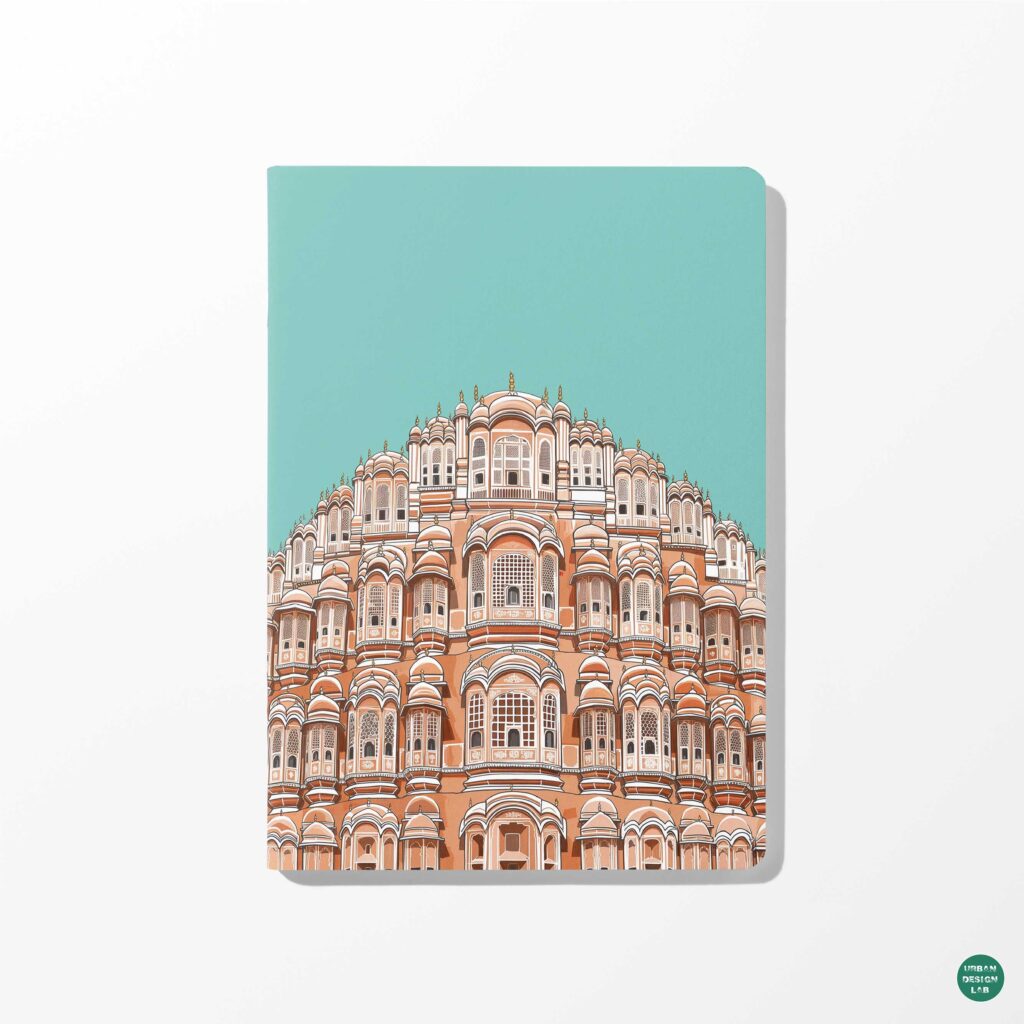

Colonial city making refers to the significant transformation of an urban settlement under colonial rule to better suit their physical, social, and administrative needs. The colonizers comfort and productivity were the primary reasons affecting design decisions, and this is seen in the architecture and urban planning of the colonized cities. European architecture is amalgamated with the native architecture to create a unique architectural style suited to the local climate and speaks of the grandeur of the colonizers. A notable example is the Indo-Saracenic architecture in India, which is a fusion of Indian and Islamic styles. However, it notably remains British in its spatial composition, owing to its function as a style showcasing the might of the British Empire.

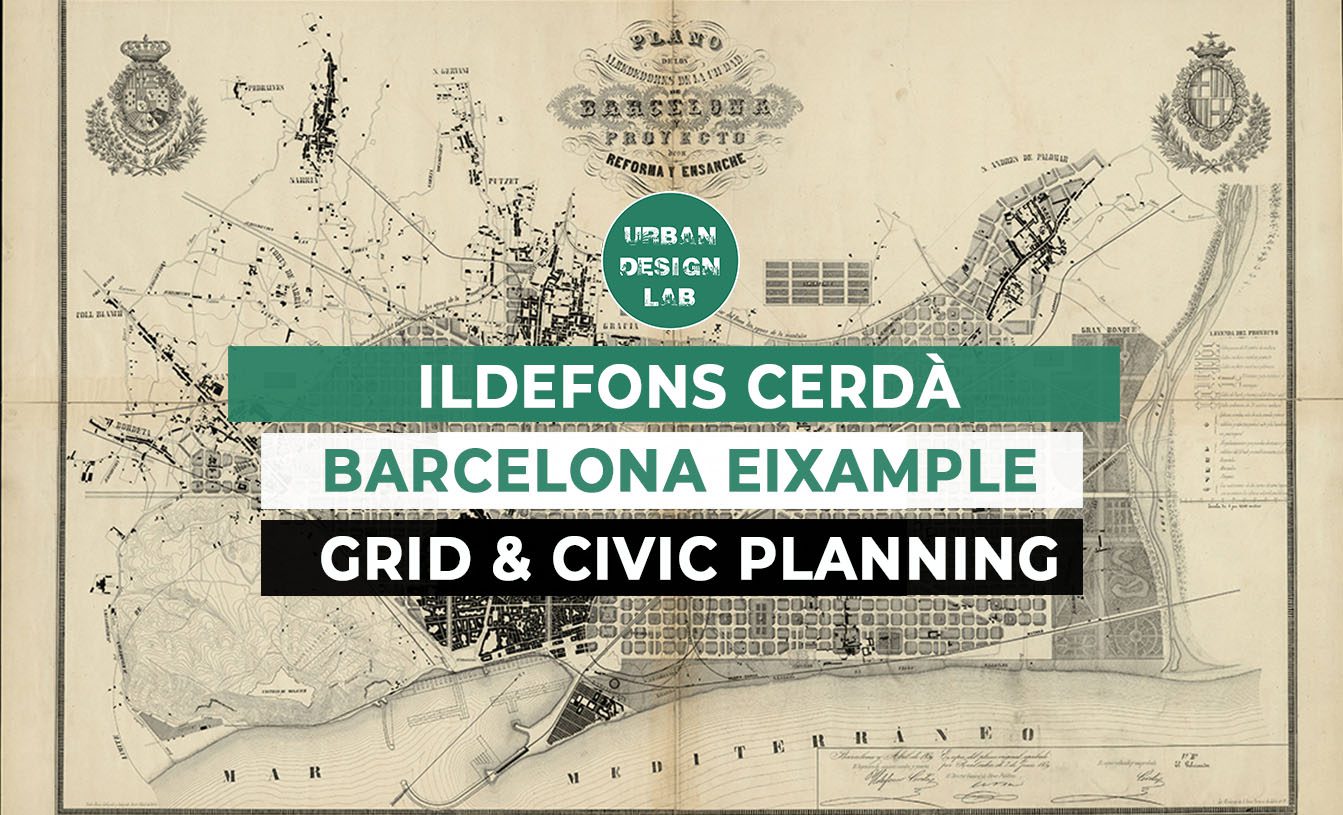

City layouts were redone to reflect planning of their hometowns. Grid layout was introduced to normally irregularly planned cities, effectively splitting them into clear-cut zones for better productivity and efficiency. This allowed them to build and reinforce white-only spaces, cutting the natives off from their own land. New landmarks were created to erase the previously held native sentiments. Slow but steady changes to the urban landscape resulted in cities almost unrecognizable to the natives.

Source: Website Link

The Law of the Indies and its influence on urban planning

The Law of the Indies refers to the body of laws issued by the Spanish crown that governs the social, political, religious, and economic life in their colonies. They recognized the importance of urban spaces as centres of economic and political power and founded their own. Their form of urban planning reflects their hometowns and principles of productivity and efficiency. Gridiron layout was the norm as it offered both high connectivity and flexibility and made it easier for the colonizer to establish a social hierarchy. The replication of this layout in all Spanish colonies showed unity and might have raised a feeling of ‘property’ of the Spanish Crown. They also showed a concern for environmental factors in Latin America by denoting and building on healthy sites and planning for public spaces.

The foundation of Barcelona in Venezuela is an example of how cities were built with little regard for local people. The merging of two previous settlements, San Cristobal de Los Cumanagotos and Santa Eulalia, gave birth to New Barcelona. However, there was no mixing of the inhabitants from the two different towns; they occupied different parts of the new city, leading to a clear divide in growth.

Dutch alienation in Indonesia

The Dutch ruled Indonesia for almost three and a half centuries, during which they made consequential changes. They initially showed almost no concern for local architecture. Instead, they cloned their cities in a tropical setting, completely erasing the context. This is evident in the leveling of the city of Batavia to create a ‘New Amsterdam.’ The new cities follow the ring-like planning of Dutch cities, with colonizers at the center enjoying better living conditions and the colonized pushed to the outer rings.

Their architecture reflected the typical Dutch pattern with neoclassical and Gothic styles at its core. As the design does not respond to the hot and humid climate, they slowly began to integrate local design techniques to give rise to a new style called Indische architecture.

The hybrid architecture style borrowed the best of both worlds with large verandas and lattice windows to address the heat and humidity. The most significant part is the use of the indigenous roof form of the extended hipped roof to create buildings that retain the European character and manage to offer comfortable living conditions. This is a powerful reflection of even if the people can be controlled, nature cannot be.

The inertia of decolonization

With such unique, long-lasting consequences on each colony, it is easy to see why it is so difficult to dismantle the social and economic hierarchy. Most colonizers left their colonies in a state of demise after sucking their resources dry and planting seeds of political unrest. At a time when people are struggling, decolonization tends to take a backseat. This pushes newly formed states to a survival mode where they must depend on colonizers way of governing, at least until the country stabilizes.

The sheer amount of time needed to decolonize their ways becomes a deterrent, as change is slow and rarely steady. Despite these challenges, nationalism and pride of the natives push for reform to reclaim their land and culture. The following examples showcase former colonies efforts in taking back their land.

Kenya—street toponymy to reclaim heritage

Streets are powerful holders of memory and remembrance. It denotes the culture of people and provides an identity. The easiest way to commemorate a person is to name a street or area after them, cementing them in everyday language. Perhaps that is why colonizers set out to rename native districts, reducing the carefully pronounced title to a collection of anglicized letters or completely changing it to a Western name. Colonial street names were another tool to exclude the natives from their own country and led to the creation of an increasingly colonial urban sphere. Local street names were replaced by British and Indian names.

By reclaiming the streets and reverting them back to indigenous African names, Nairobi, Kenya, took the process of decolonizing their country one step further. Street toponymy becomes a tool to remember freedom fighters and celebrate their countries rich history. The process of renaming is also an administrative one, which became uneven due to a lack of consideration in creating a specialized team for this process. This unevenness reflects the time-consuming nature of reverting colonization’s consequences for even the seemingly simple procedure of renaming streets.

Indigenous resilience in a free country

Chicago’s Humboldt Park has a complex history and is home to art belonging to different ethnicities. Statues include Leif Erikson, installed by the Norwegian community, and Alexander von Humboldt, erected by the German community. When the Puerto Ricans attempted to install a statue of Albizu Campos, a leading figure in the Puerto Rican independence movement, they were met with resistance from the Chicago Park District.

This led to the rise of La Casita de Don Pedro, a beautiful placemaking initiative built on the vacant lots of Division Street. Designed and created by students as a part of a six-week summer employment program, it is the home of the statue and showcases the culture of Puerto Rico. This place has hosted hundreds of cultural events and political rallies. Now, Humboldt Park and the surrounding area are the only official Puerto Rican cultural district in the USA. This example is a testament to the resilience and creativity of the Puerto Ricans in a city where they face resistance and mistrust.

Urban planning in a former colony—Amaravati, India

Amaravati was envisioned as the capital city for the state of Andhra Pradesh by Foster and Partners. Set on the banks of the Krishna River, the 217-square-kilometer city is inspired by Lutyens’s New Delhi and New York’s Central Park. There is a greater emphasis on sustainability with a central green spine and at least 60% of the area being covered by greenery or water. The government complex forms the heart of the city, offering efficient connectivity and accessibility. The planning follows a strong urban grid reminiscent of New York.

The urban planning still follows the Western ideal, which may not be the most appropriate choice for India, where citizens thrive in informal streets and places. The rigid planning may be considered too radical for the state, which has not had prior exposure to formality. This reflects how former colonies still look up to their colonizers and try to emulate their ideas even if it will not be the best fit for their context and climate. The plan was abandoned due to the pullout of major investors, and the Western idealized utopia only exists in beautiful renders.

Conclusion

The case studies present the deeply entrenched values of colonization, which affect the world even today, favoring the colonizer and injustice to the colonized. The process of decolonization cannot happen overnight and requires active participation by all countries to right the wrong. However, the huge amount of time needed to change people’s mindsets is itself a key factor in the resistance.

All hope is not lost, as examples like Humboldt Park set a model for the ingenuity of natives in the face of hostility. The initiative led by students instills confidence for the future generations. Kenya’s immediate decision to begin the process of renaming their streets after their independence proves their commitment to decolonization. These examples illustrate that erasure of culture is no longer an option. Change by design is the key to a better future where indigenous practices are celebrated, not eroded. Design is a tool to right the wrongs of the past and has the power to return the country to whom it belongs.

References

- Isa, F., Al-Aggad, H., Al-Quthami, L., & Wazna, N. (2022). The architecture of colonialism. Civil Engineering and Architecture, 10(3A), 118–125. https://doi.org/10.13189/cea.2022.101315

- Mundigo, A. I., & Crouch, D. P. (1977). The City Planning Ordinances of the Laws of the Indies Revisited: Part I: Their philosophy and Implications. Town Planning Review, 48(3), 247. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.48.3.g58m031x54655ll5

- Heryanto, B. Urban Form of Indonesian Cities During the Colonization Period. Pasca.unhas.ac.id.

- Wanjiru, M. W., & Matsubara, K. (2016). Street toponymy and the decolonisation of the urban landscape in post-colonial Nairobi. Journal of Cultural Geography, 34(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2016.1203518

- Fernandes, J. (2024, March 14). The politics of Dis-Belonging. Shelterforce. https://shelterforce.org/2016/09/21/the-politics-of-dis-belonging/

- Amaravati MasterPlan | Foster + Partners. (n.d.). https://www.fosterandpartners.com/projects/amaravati-masterplan

Vijetha Ravindran

About the author

Vijetha Ravindran is an undergraduate student of architecture at Thiagarajar School of Environmental Design and Architecture, Madurai, India. From Chennai, her interest in design rose from exposure to different built environments due to frequent traveling in her early years. Her main interest in research is about the use of artificial intelligence in the allied fields of design and architecture and placemaking to build people-centric cities. Her work reflects a commitment to people-centric buildings and designs with an emphasis on spatial experience.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “