How Tactical and Landscape Urbanism Shape Sustainable Urban Futures

This article explores two complementary urban planning approaches for a sustainable future. Tactical urbanism involves community-led, short-term, low-cost interventions (like parklets, pop-up parks, and guerrilla planting) to quickly reclaim and improve public spaces. These grassroots projects test new ideas and often lead to safer, greener streets and plazas. Landscape urbanism is a large-scale, system-oriented strategy that treats the city as an interconnected network of parks, waterways, and ecological systems rather than isolated buildings. It emphasizes ecology and infrastructure (green roofs, bioswales, urban forests) to adapt to climate change and support urban life. By blending these approaches, using tactical projects to build support and inform design, while embedding nature-based strategies into city planning, cities can become more resilient and equitable. Real-world examples (from neighbourhood parklets to major riverfront redevelopments) show how these frameworks help cities adapt and thrive. Together, tactical urbanism and landscape urbanism create a holistic urban framework that promotes environmental health, community well-being, and long-term sustainability.

Tactical Urbanism: Grassroots Urban Interventions

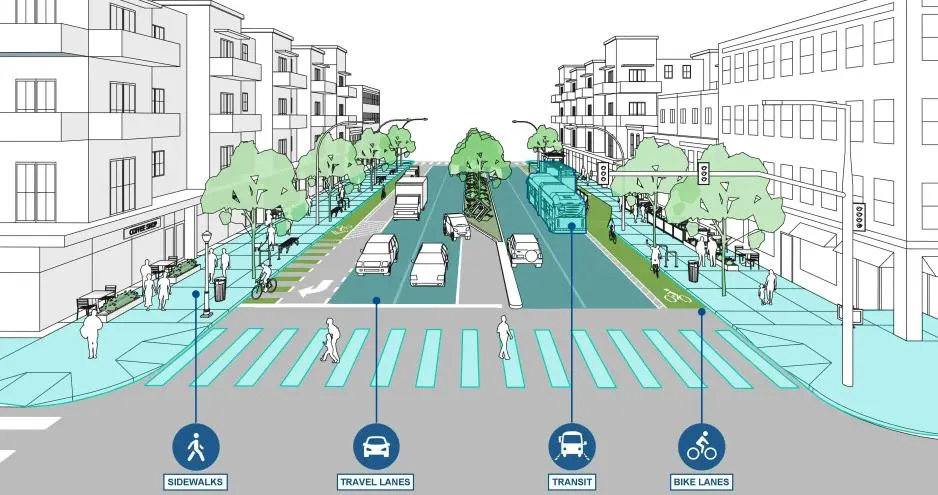

Tactical urbanism refers to rapid, short-term, and often volunteer-led changes to public spaces. Small projects, such as temporary plaza installations, painted curb extensions, or weekday street festivals, quickly transform streets or parking spaces into usable community areas. Because these interventions are low-cost and scalable, citizens and local groups can implement them without waiting for major bureaucratic processes. Such ‘urban acupuncture’ projects immediately improve pedestrian safety, add greenery, or create social hubs. Over time, many have led to permanent change. For example, the annual Park(ing) Day initiative showed how turning car parking spots into mini-parks raises awareness and support for more permanent parklets. By reclaiming vehicle-dominated areas, tactical urbanism empowers residents to repurpose space for public benefit, laying a foundation for longer-term planning.

Empowering Communities through Tactical Projects

Beyond specific installations, tactical urbanism builds social capital by involving people directly in reshaping their streets. Neighbours might paint colourful crosswalks at dangerous intersections, install pop-up bike lanes to promote cycling, or create guerrilla gardens in vacant lots to grow food and native plants. These projects often start with a small group but quickly garner broader support as residents see real benefits, improved air quality, more shade, or safer play areas for kids. In many cities, such citizen projects have prompted local governments to formalize and expand them. By proving concepts on a small scale, tactical urbanism lowers the risk of new ideas. Successful temporary projects (like expanded sidewalk cafés or seasonal bike paths) have sometimes been made permanent by planners. In this way, tactical urbanism acts as an experimental lab: it tests changes, engages diverse stakeholders, and helps define what sustainable, people-friendly streets can look like in practice.

Source: Website Link

Landscape Urbanism: Ecological City Design

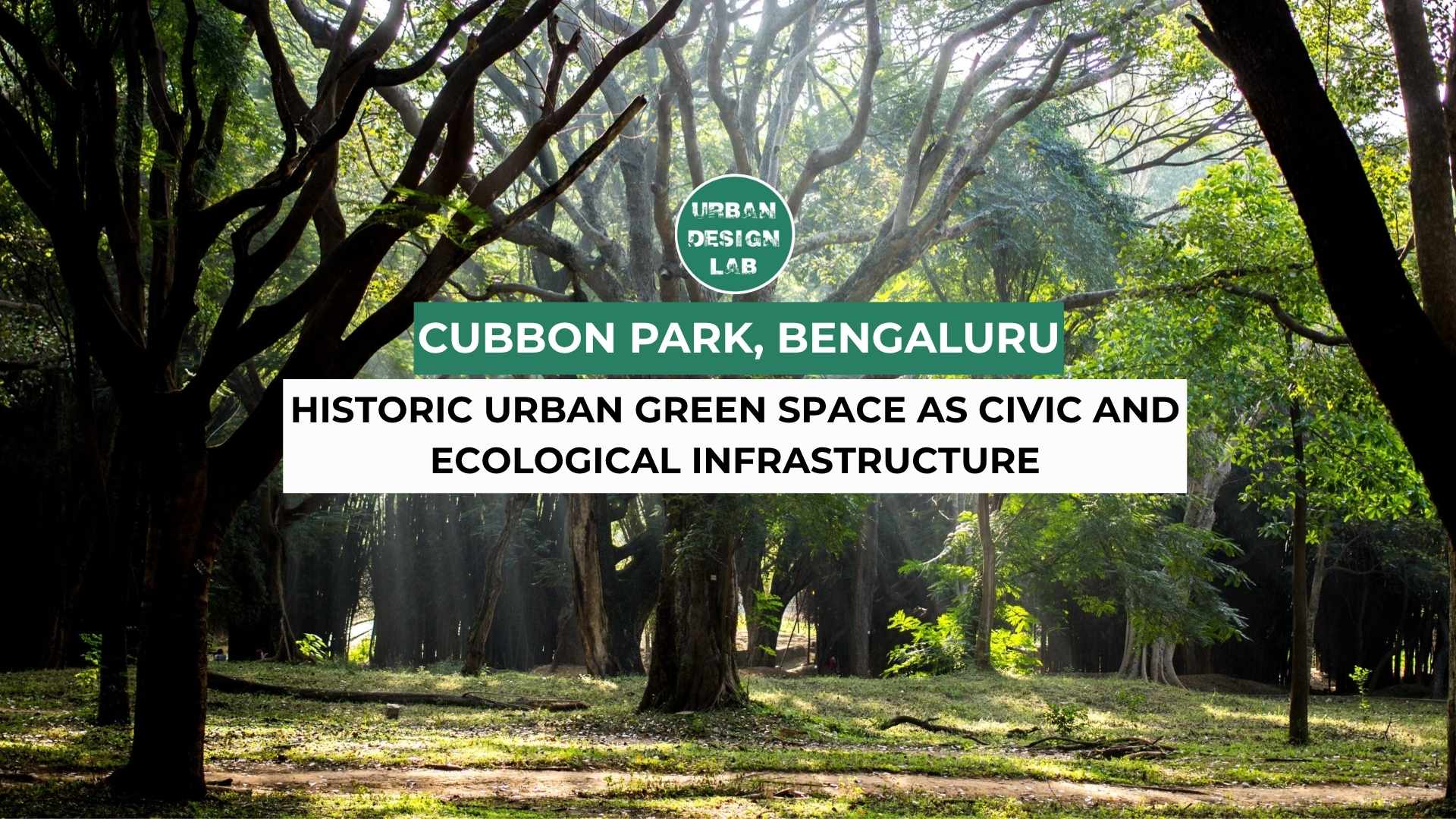

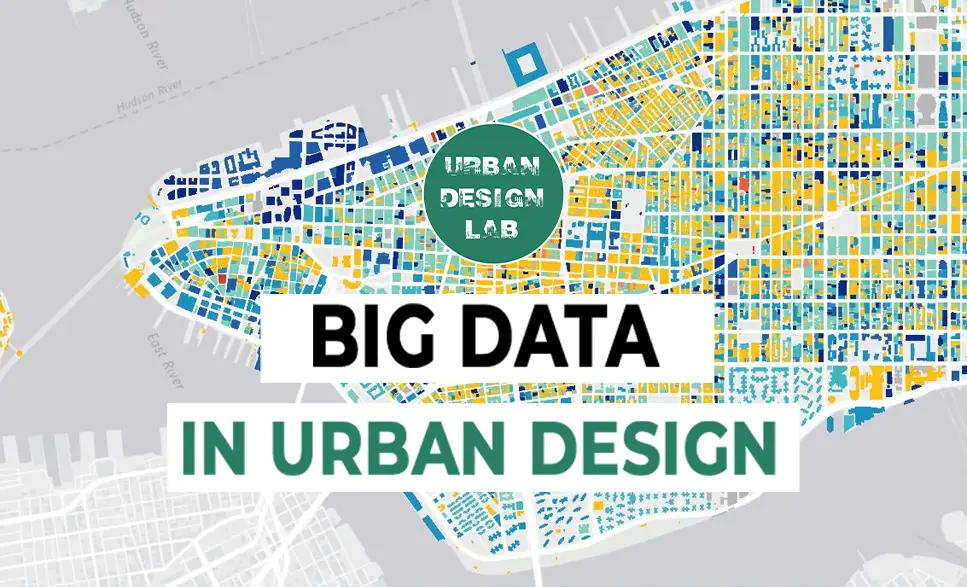

Landscape urbanism is an approach that sees the city as an integrated ecology of landscapes and systems. Instead of focusing on individual buildings or streets, it organizes urban growth around green networks, parks, waterways, gardens, and green infrastructure, that flow through the city. In this view, the ‘fabric’ of the city is made up of interconnected ecological fields that support habitat, manage water, and shape public life. Prominent landscape urbanist thinkers argue that large-scale forces (ecological flows, stormwater, transportation) define 21st-century cities more than the architecture of single buildings. For example, projects like converting abandoned railways into linear parks or building plazas over sunken highways treat landscape as a structuring element. By designing for natural processes (stormwater runoff, habitat, microclimate), landscape urbanism creates an urban form that is adaptable and environmentally rich.

Integrating Ecology and Infrastructure

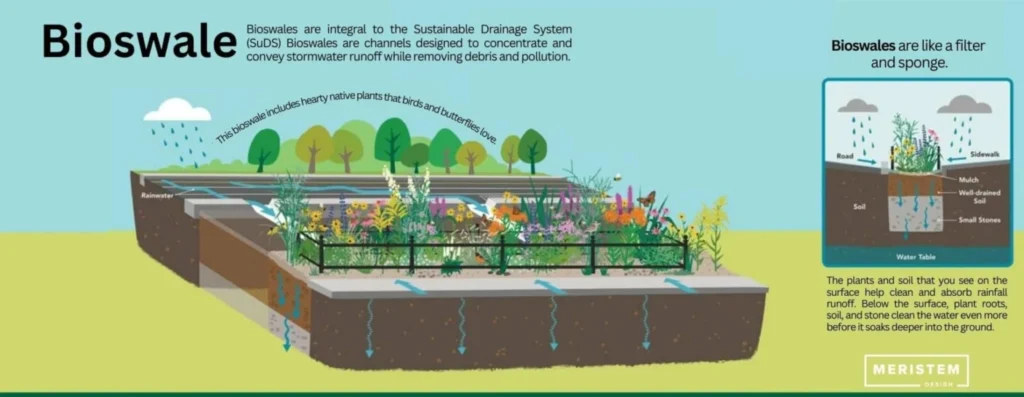

A key tenet of landscape urbanism is embedding green infrastructure into urban systems. Features like rain gardens, permeable pavements, bioswales, green roofs, and urban wetlands help cities manage floods, filter pollutants, and lower heat islands while providing public amenities. These nature-based solutions turn challenges (like stormwater) into design opportunities. For example, a road median planted with native grasses can absorb rainfall and reduce runoff, while offering habitat and visual appeal. On a larger scale, daylighting rivers or expanding urban forests reconnect neighbourhoods with nature. Such interventions make cities more resilient to climate impacts and improve ecosystem services. By planning streets and districts around living systems, rather than only asphalt and pipes, landscape urbanism ensures that new development contributes to environmental sustainability.

Green Infrastructure: Building Resilient Urban Ecosystems

In practice, landscape urbanism often overlaps with the concept of green infrastructure, an interconnected network of parks, gardens, street trees, and greenways that performs ecological functions. Cities worldwide are planting pollinator gardens, creating urban farms, and restoring wetlands to increase resilience. These interventions provide habitat for wildlife, sequester carbon, and help cool neighbourhoods during heat waves. For instance, replacing a parking lot with a rain garden not only absorbs rainwater but can host public art or playgrounds. Even small-scale plantings, like sidewalk planters or rooftop gardens, contribute to a larger urban ecosystem. By thinking in terms of layered green networks instead of isolated parks, planners can create healthier environments. This green framework also yields social benefits: community gardens bring neighbours together, and visible nature in daily life improves mental health.

Urban Agriculture and Community Resilience

Tactical and landscape approaches converge strongly in urban agriculture and community gardening initiatives. Turning vacant lots or rooftops into gardens or farms is both a tactical act of reclaiming space and a landscape-scale strategy for local food systems. These projects demonstrate how cities can produce some of their own food, reducing transportation emissions and providing fresh produce. In many neighbourhoods, volunteers build raised beds, plant orchards, or install hydroponic gardens, often on public or unused land. These gardens enhance green cover and support pollinators while empowering residents with new skills. Over time, successful community farms can influence zoning and development, encouraging cities to include urban agriculture in long-term plans. By integrating farming into the urban landscape, cities become more adaptable to supply shocks and more connected to nature, embodying the ideals of both tactical and landscape urbanism.

Integrating Approaches for Sustainable Cities

Tactical urbanism and landscape urbanism each offer distinct but complementary strategies. Small, temporary projects can pilot ideas that later inform city-wide planning, while large-scale landscape plans can be incrementally built with community input. For example, a tactical parklet pilot might demonstrate demand for a permanent plaza. Conversely, a greenway plan may start with citizen stewardship of a single block. Policymakers and planners can bridge these approaches by formalizing successful tactics into policy, funding long-term ecological projects, and encouraging public participation in both. Key strategies include adaptive zoning for community gardens, incentives for green building features, and programs supporting volunteer urban greening. Challenges remain in equity (ensuring all communities benefit) and measuring impact, but by combining bottom-up experimentation with top-down vision, cities create a flexible framework. Together, these methods ensure future urban growth is not only efficient, but also livable and regenerative.

Conclusion

A sustainable urban future requires both hands-on experimentation and strategic planning. Tactical urbanism’s community-driven projects reveal immediate possibilities and build public enthusiasm for change, while landscape urbanism embeds ecological thinking into the city’s blueprint. By harnessing small-scale interventions alongside comprehensive green infrastructure plans, cities can become more resilient, equitable, and environmentally healthy. This dual framework, one tactical, one landscape, makes cities adaptable to climate, economic, and social challenges. Urban designers and planners should use tactical projects as living experiments and integrate their successes into long-term designs. In this way, neighbourhoods and citywide systems evolve together. Ultimately, a blend of both approaches guides us toward truly sustainable, vibrant cities where people and nature thrive.

References

- Wortman, A. (2015, May 19). Everything you wanted to know about Tactical Urbanism. The Dirt (American Society of Landscape Architects). Retrieved from https://dirt.asla.org/2015/05/19/everything-you-wanted-to-know-about-tactical-urbanism/

- Yacoubou, J. (2024, June 25). What is Tactical Urbanism? 4 Examples & Case Studies. Green Building & Design. Retrieved from https://gbdmagazine.com/tactical-urbanism

- Gintoff, V. (2016, April 6). 12 Projects that Explain Landscape Urbanism and How It’s Changing the Face of Cities. ArchDaily. Retrieved from https://www.archdaily.com/784842/12-projects-that-show-how-landscape-urbanism-is-changing-the-face-of-cities

- Dutta, A. J. (2023, July 26). Transforming Urban Spaces through Landscape Urbanism Interventions. Urban Design Lab. Retrieved from https://urbandesignlab.in/transforming-urban-spaces-through-landscape-urbanism-interventions/

Shivani Patil

About the Author

Shivani Patil is an architecture graduate from India and a postgraduate in Urban Design from the United Kingdom. With a strong academic foundation and a keen interest in sustainable and inclusive urbanism, she explores the intersections of design, planning, and community-driven development. Her work reflects a passion for resilient cities, innovative public spaces, and participatory design strategies. Shivani is particularly drawn to how emerging technologies and ecological approaches can reshape urban futures. Through this internship, she aims to contribute meaningfully to the discourse on equitable and future-ready urban environments.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “