Ildefons Cerdà – Barcelona Eixample Grid & Civic Planning

Ildefons Cerdà, a 19th-century Spanish engineer and urban planner, left a lasting legacy through his revolutionary plan for Barcelona’s expansion. Known as the “Eixample” (meaning “extension”), Cerdà’s grid-based design transformed the city’s urban landscape.

Departing from the cramped medieval layout toward a new model grounded in health, accessibility, and egalitarianism, his design principles were documented in his seminal work Teoría General de la Urbanización (1867), which became one of the earliest comprehensive urban planning theories.

At the core of Cerdà’s approach was the belief that urban design should serve public health, facilitate mobility, and promote social equality. His plan, although never fully realized as he intended, set new benchmarks for civic infrastructure, spatial organization, and planning methodologies.

The Eixample was not merely a spatial solution—it was a moral and social one. This article explores the origins, principles, implementation, and enduring impact of Cerdà’s grid, analyzing its theoretical foundations, practical adaptations, and legacy within contemporary urbanism.

By examining each layer of his vision, we gain insight into how one man’s ideas continue to shape modern cities and inspire planners globally.

Historical Context: Barcelona’s Urban Crisis and the Need for Expansion

In the mid-19th century, Barcelona faced a severe urban crisis. Confined by medieval walls, the city suffered from overcrowding, poor hygiene, and lack of green space.

The effects of industrialization and rapid population growth overwhelmed the city’s infrastructure. Diseases like cholera spread through dense neighborhoods, and average life expectancy plummeted. Sanitation, housing, and mobility infrastructure were inadequate for the expanding working-class population.

Civic unrest and public health emergencies led to calls for a radical solution. Ildefons Cerdà, trained as an engineer, undertook detailed studies of Barcelona’s urban conditions. He analyzed housing density, street widths, sanitation, and social inequality.

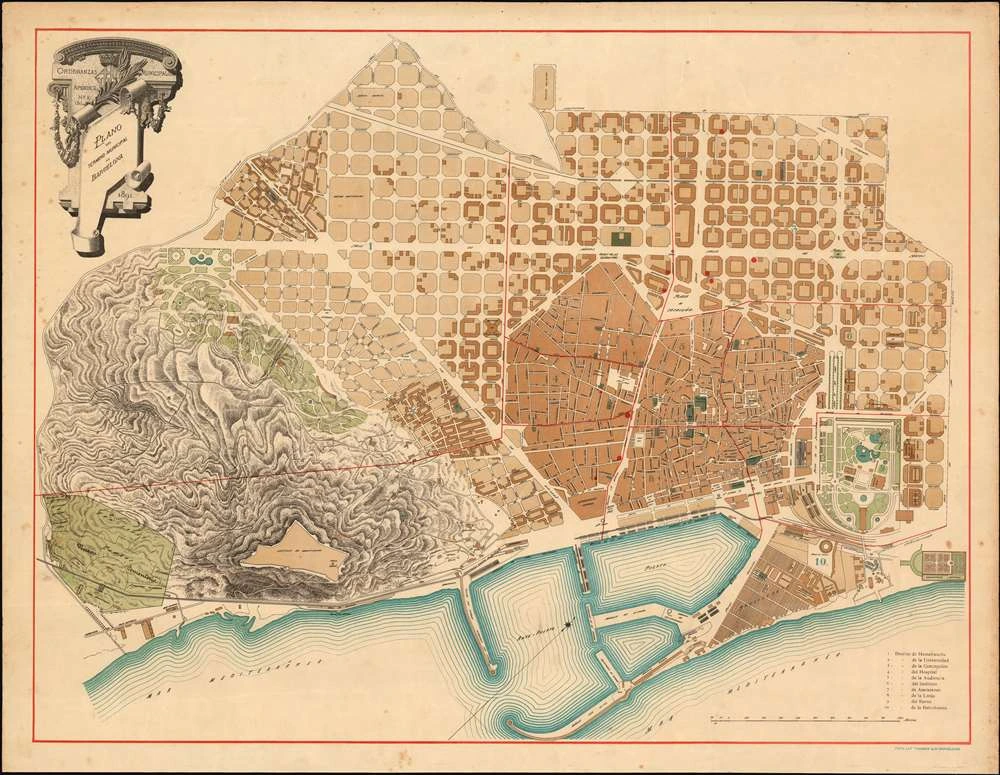

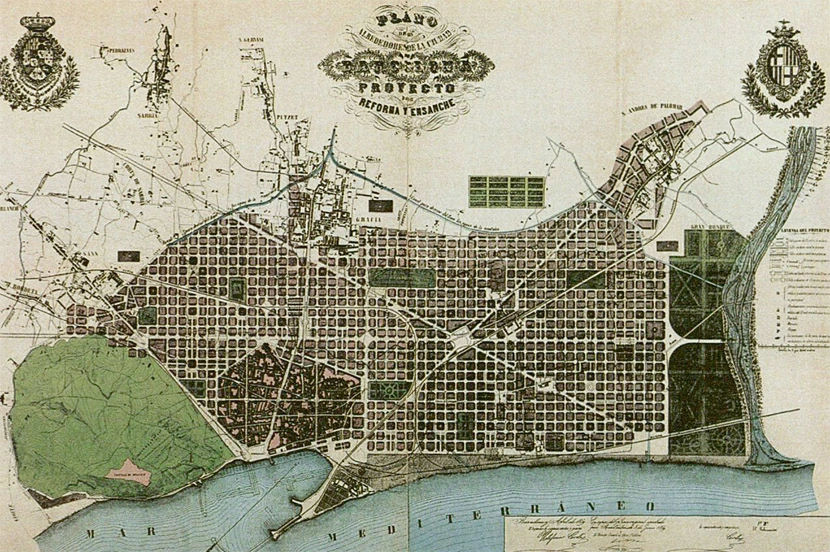

In 1859, Cerdà proposed the Pla d’Eixample, a visionary expansion plan for the city beyond its medieval boundaries. Despite opposition from the Barcelona City Council, the Spanish central government approved his plan due to its scientific rigor and public health focus.

Cerdà’s vision was grounded not just in engineering but in the belief that cities should serve the collective well-being of all citizens. His plan became the foundation of a new urban paradigm: rational, human-centric, and designed for a healthier civic life.

Design Principles: Geometry, Functionality, and Equity

Cerdà’s Eixample plan was defined by a strict geometric grid of octagonal blocks, each measuring 113 by 113 meters. Chamfered corners (chaflans) improved visibility and facilitated turning at intersections.

This distinctive design was more than aesthetic; it served practical and ethical goals. The wide streets, often between 20 and 60 meters, were intended to allow sunlight, air circulation, and movement of traffic—all essential for public health.

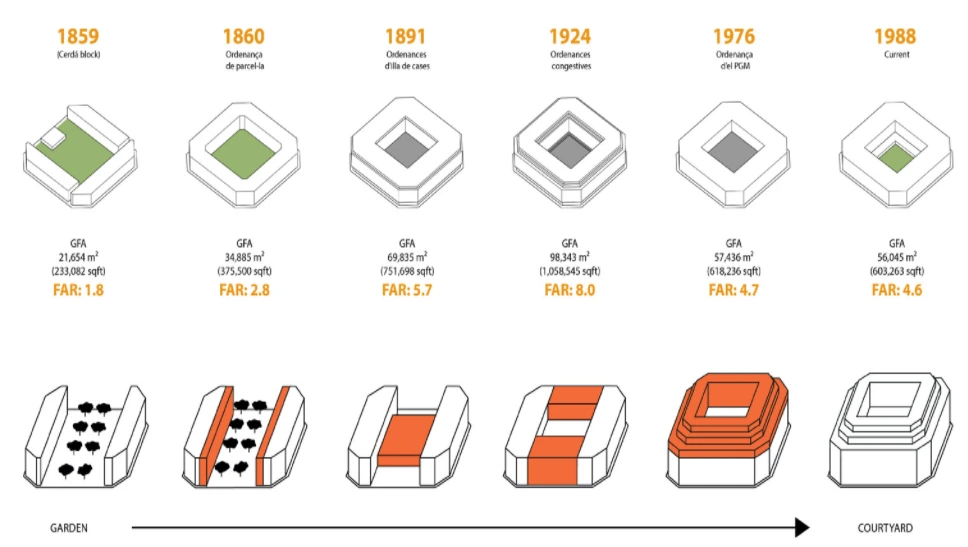

Cerdà envisioned buildings no higher than 16 meters, surrounding communal courtyards designed for greenery and recreation. Every block was meant to include space for residents to interact and access light and air equally.

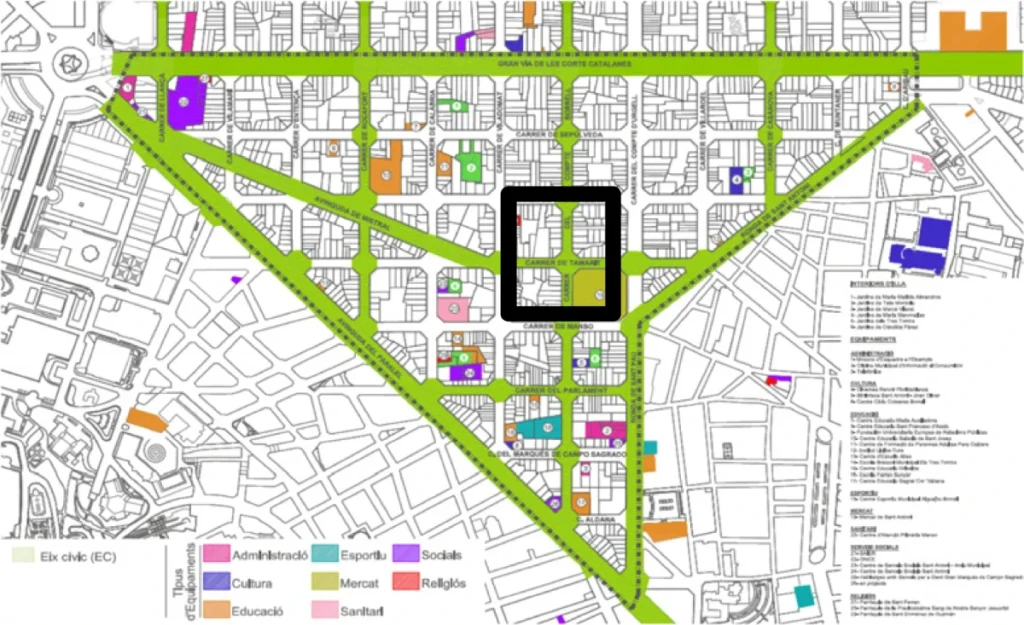

His approach promoted mixed-use zoning long before the term existed, aiming for residential, commercial, and public uses to coexist within walking distance. Infrastructure—such as sewerage, water, and gas—was planned in advance, a major innovation.

Above all, equity was central: no part of the city was to be favored over another. This was a sharp contrast to elitist urban planning in other European cities, where grand boulevards catered to the wealthy.

Though later development often violated these ideals, Cerdà’s foundational principles remain revolutionary in their attention to livability and fairness.

Source: Website Link

Implementation: Political Resistance and Partial Realization

Despite its forward-thinking nature, Cerdà’s plan encountered strong opposition. Barcelona’s local government had favored a competing proposal by architect Antoni Rovira i Trias, which focused on monumental, radial layouts catering to elite interests.

Cerdà’s rational, egalitarian design clashed with local preferences. However, the Spanish central government approved his plan in 1860, citing its sanitary and technical superiority.

This approval inflamed local tensions. Developers and landowners resisted parts of the plan, especially its limits on building heights and insistence on communal courtyards. Profit motives led many to fill in green courtyards with buildings, reducing open space.

Although the grid layout and chamfered corners were preserved, other key features—such as consistent green zones and public-use planning—were gradually diluted by private interests.

Moreover, only parts of the proposed infrastructure and social amenities were implemented. The plan became a battleground between utopian ideals and economic realities.

Yet, despite its partial execution, the Eixample still reshaped Barcelona. Its orderly grid, infrastructural foresight, and modern logic laid the groundwork for a livable, walkable, and dynamic city.

Civic Ideals: Public Health, Mobility, and Social Justice

Cerdà was more than an engineer—he was a civic thinker. His plan sought to remedy deep social inequalities embedded in urban form. He aimed to create a city that promoted justice through spatial organization.

Public health was central. He studied disease patterns and understood that narrow, congested streets were breeding grounds for illness. His grid’s generous street widths, ventilation, and sunlight access were deliberate antidotes.

Mobility was another priority. The grid allowed for efficient movement of people, goods, and services. Cerdà anticipated the rise of trains and streetcars and ensured that infrastructure could support future transport systems.

Crucially, he believed urban benefits—like light, air, water, and green space—should be distributed equally. His design rejected the class-based segregation seen in other European cities, advocating instead for accessible, dignified living for all.

His writings foreshadow today’s discussions around the “right to the city.” Though developers compromised his ideals over time, the foundational ethics of inclusion and accessibility remain embedded in his vision.

Cerdà saw urbanism not just as design, but as social reform—a perspective that continues to inspire planners focused on equity and sustainability.

Enduring Legacy: Influence on Global Urban Planning

Cerdà’s influence extended far beyond Barcelona. His data-driven, human-centric approach shaped urban thought across Europe and Latin America.

In cities like Buenos Aires, the Cerdà-style grid was adapted for new neighborhoods. In San Francisco and parts of Vancouver, similar principles were adopted to optimize circulation, sunlight, and access.

Barcelona itself has revisited his legacy through the “superblocks” program, which consolidates multiple Eixample blocks into car-free zones prioritizing pedestrians, bicycles, and green areas. This is a modern reinterpretation of Cerdà’s social and environmental priorities.

Cerdà’s holistic view of the city—one integrating hygiene, transportation, infrastructure, and equality—anticipated the multidimensional thinking required in contemporary urban planning.

His Teoría General de la Urbanización is still referenced in urban studies and planning curricula as a foundational text. His use of empirical data and analytical maps was ahead of its time and remains influential in GIS-based planning today.

While the full vision of Eixample was never realized, Cerdà’s principles continue to shape resilient, inclusive, and sustainable cities worldwide. His legacy underscores the idea that urban planning can and should serve the common good.

Conclusion

Ildefons Cerdà’s Eixample plan is more than an urban design—it is a philosophy rooted in civic responsibility and social justice.

His principles of health, mobility, and equity remain relevant as cities confront modern challenges like climate change, housing crises, and car dependency. The Eixample, though altered over time, still demonstrates how geometry, infrastructure, and ethical planning can foster more inclusive urban life.

Cerdà’s vision continues to inspire planners who prioritize walkability, sustainability, and accessibility. In the age of the “15-minute city,” where essential services should be reachable without a car, his human-scale design feels more vital than ever.

By combining engineering with ethics, Cerdà created a model that transcends time. His work invites cities to be not only efficient but just—to serve everyone equally and promote collective well-being.

Today’s planners, policymakers, and citizens can still learn from his approach: treat the city as a system, use data to inform design, and never forget that behind every plan are the lives it aims to improve.

References

- Cerdà, I. (1867). Teoría General de la Urbanización.

Read on Cervantes Virtual - Busquets, J. (2005). Barcelona: The Urban Evolution of a Compact City.

Harvard GSD - López, D. (2014). “Cerdà and the Barcelona Eixample.” Urban Studies, 51(2), 307–324.

DOI Link - Capel, H. (2002). “Urban Planning in Spain: The Legacy of Cerdà.” Town Planning Review, 73(3).

University of Liverpool - Monclús, J. (2003). “The Barcelona Model.” Cities, 20(6), 361–369.

ScienceDirect - Marshall, T. (2004). Transforming Barcelona.

Google Books - Rueda, S. (2019). “Superblocks for the Design of New Cities.” Sustainability, 11(17), 4840.

MDPI - Bohigas, O. (1999). Reconstrucción de Barcelona.

WorldCat - Muñoz, F. (2008). Urbanalisation: Globalising Space.

Editorial Gustavo Gili - Brunn, S. & Wilson, M. (2013). The Routledge Companion to Urban Geography.

Routledge

Salah ALDeen Amr Ahmed Mohamed

About the Author

Salah Amr is an architecture student at the Canadian International College (CIC) in Egypt. His academic focus lies in sustainable design, urban planning, and the integration of technology in architectural solutions. He is particularly interested in how data-driven approaches and smart systems can enhance the functionality and inclusivity of urban spaces. Through his studies, Salah aims to contribute to innovative and responsible urban development that balances environmental, social, and cultural needs. He actively engages in design projects and research that reflect a commitment to forward-thinking architecture and resilient city planning.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment

This is very enlightening especially for me also having an architectural background and majoring in urban design at Master level.. haven’t heard about this name before Ildefon cedar but now I have known better…