Modernist City Planning Ideals: A Roadmap to Decline?

The Modernist Movement

The 20th century, with its conflicts, innovations, and paradigm shifts, gave rise to significant movements in the realms of philosophy, art, architecture, culture, etc. The architectural practice itself experienced the conception of a wide range of movements – with most attempting to search for meaning, perspective, and identity following the events of the first world war. The modernist movement, born out of the shock of WWI and technological innovation, was one of them. It was characterized by the pursuit of new ways of capturing experience and claiming identity, all while rejecting traditional structures of 19th century realism including religion, state, and collective culture. With this rejection of classist ideals and ornamentation, modernist projects focus on simplicity, minimalism, and the application of basic geometries. Innovations in materials and technology enabled the construction of taller and lighter structures using glass, steel, and concrete.

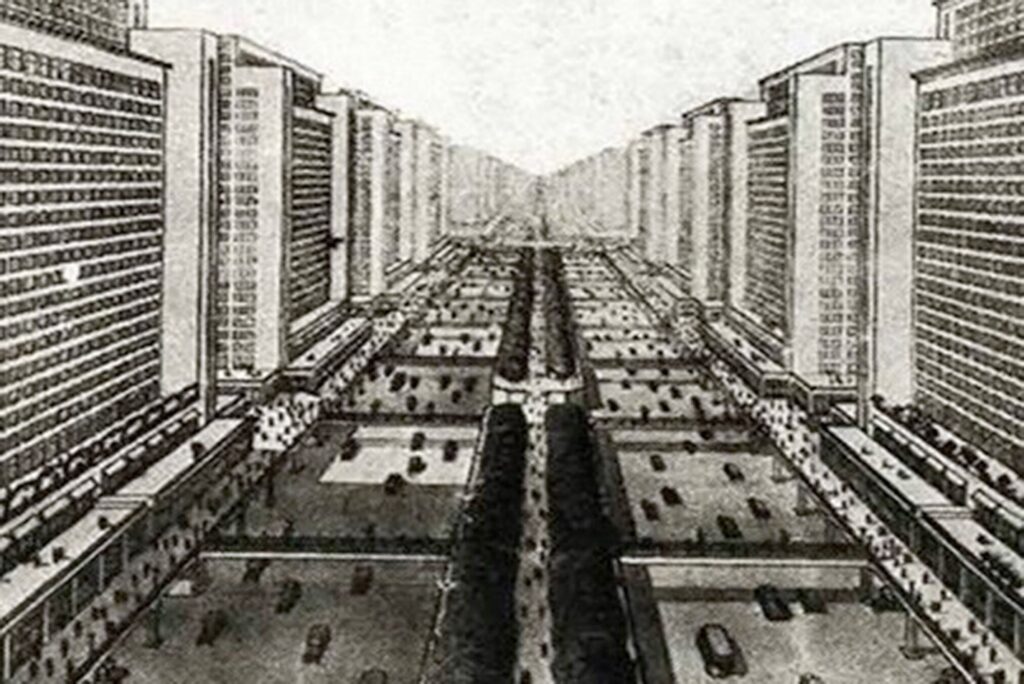

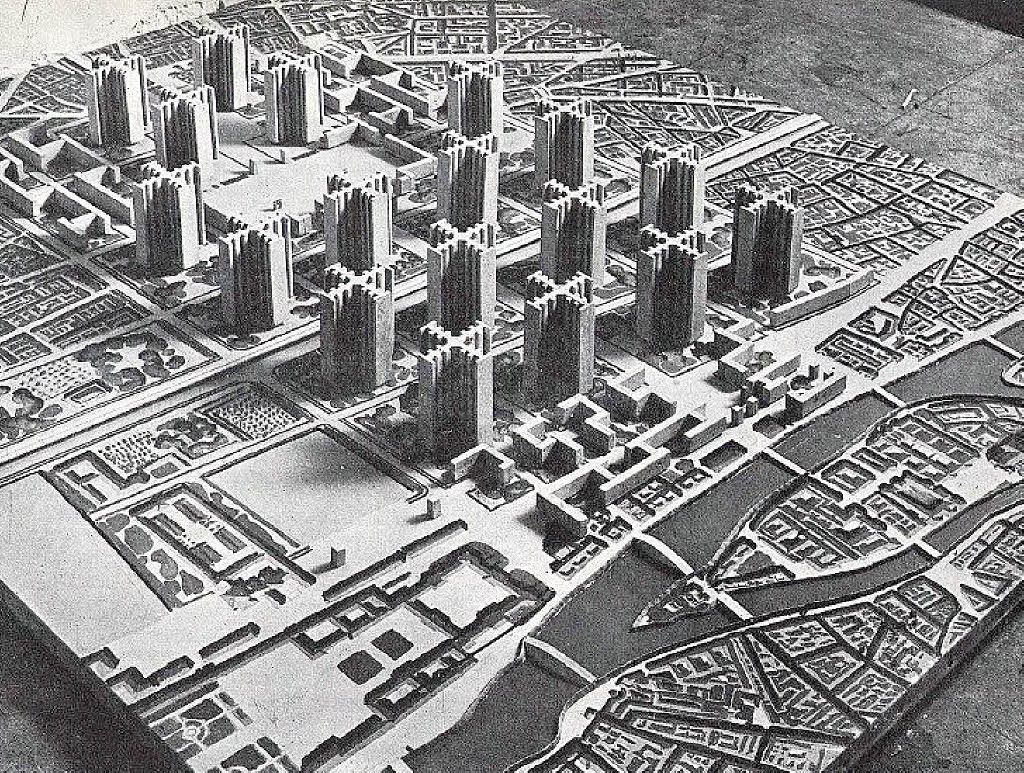

This analytical use of materials and rejection of ornamentation contributed to the simplification of form and the subsequent emphasis on functionality. While key modernist figures like Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, Kenzo Tange, etc. experimented and interpreted these ideals at the international scale, Le Corbusier’s proposed principles on urban high-rise housing, embodied in his masterplan, Ville Radieuse or The Radiant City, would have a lasting influence on public housing projects throughout the world.

His masterplan envisioned a brighter and healthier urban future. Ville Radieuse can be characterized by high-rise housing towers aligned symmetrically along a grid, framed by ample green space and both pedestrian and automobile infrastructure. These towers were designed to be self-sustaining, providing the complete range of amenities and services for its residents. This was Le Corbusier’s vision for the utopian urban center – where culture, ornament, and other “frivolous” elements came to die and efficiency in function was the catalyst for success.

Ville Radiuse, while never realized, has had an extensive influence on the development of high-density public housing blocks throughout the world. But while his masterplan provided a framework to develop high-density, cost-effective, and easily constructed housing towers, the public housing projects that realized its core principles are far from utopias. In many cases, most commonly in the United States and Soviet Russia, these housing blocks have become associated with urban squalor, poverty, crime, and neglect. These projects, often part of urban renewal or slum clearance initiatives in the United States, have garnered widespread criticism and become synonymous with the failings of modernist architecture. That being said, there are cases, most commonly in parts of Asia and Europe, where these projects succeed and take flight – providing their residents with healthy, rich urban experiences and realizing, to an extent, Le Corbusier’s vision for a better future.

This article uses three public housing projects founded upon modernist principles to illustrate and provide insights into the social, cultural, political, and ideological factors that determine whether these projects succeed or fail. These three precedents are Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, Housing Development Board housing towers in Singapore, and The Comfort Town in Ukraine.

Pruitt-Igoe, United States

The Pruitt-Igoe housing projects, a joint development involving Wendell O. Pruitt Homes and William Igoe Apartments, was constructed in the 1950s in St. Louis, Missouri, United States to accommodate for the increasing demand of housing following the events of WWII. It was built as part of the city’s urban renewal program, clearing and revitalizing urban slums. Designed by the architect Minoru Yamasaki, Pruitt-Igoe were heavily influenced by modernist ideals and Le Corbusier’s vision for a new urban setting.

Made up of 33 concrete high-rise towers lacking any form of ornamentation and arranged neatly on a grid, the development was one of the most prominent examples, in its time, of modernist principles at play. Opened to the public in 1954, Pruitt-Igoe was initially a strong success for the urban renewal program. It provided critical housing supply and offered a new urban experience to the community. But within the next few years, conditions would begin to rapidly degrade. The projects experienced lowered occupancy rates and infrastructure failure. By the end of the 1960s, these issues escalated to crime, gang violence, deteriorating amenities, poor maintenance, and lack of social cohesion. All 33 buildings were demolished in 1976, only a little over 20 years since they’re opening.

Pruitt-Igoe has become known as the most infamous public housing disaster in recent history. But what factors most greatly shaped its decline? There are two mainstream opinions surrounding this question:

Its harshest critics believe that its spiral into urban ruin was caused by its modernist roots. Considered the “death of modern architecture,” its critics believe that modernist architectural principles – the rejection of culture, ornamentation, and identity and the subsequent refocus towards functional simplicity – enable and provoke the development of housing projects that do not meet basic standards of living. This culture, motivated by low costs and fast construction times, delivers structures that are untested, haphazard, and whose management needs cannot be met by its developers. Due to these tendencies, modernist structures are usually criticized for existing beyond the human-scale and undervaluing human wellbeing.

While some point to modernist ideals, many also attribute the decline to a complex combination of social, cultural, and governance factors specifically in post-war United States. The Pruitt-Igoe Myth, a documentary by Chad Freidrichs, claims that the social collapse of the development was merely a reflection of the greater city’s economic and socio-culture hardship. Freidrich’s documentary stated that racial demographics and modernist ideals were used as scapegoats for the greater forces at play – and that this fallacy perpetuates the misconceptions of public housing projects in the United States.

Singapore’s Public Housing

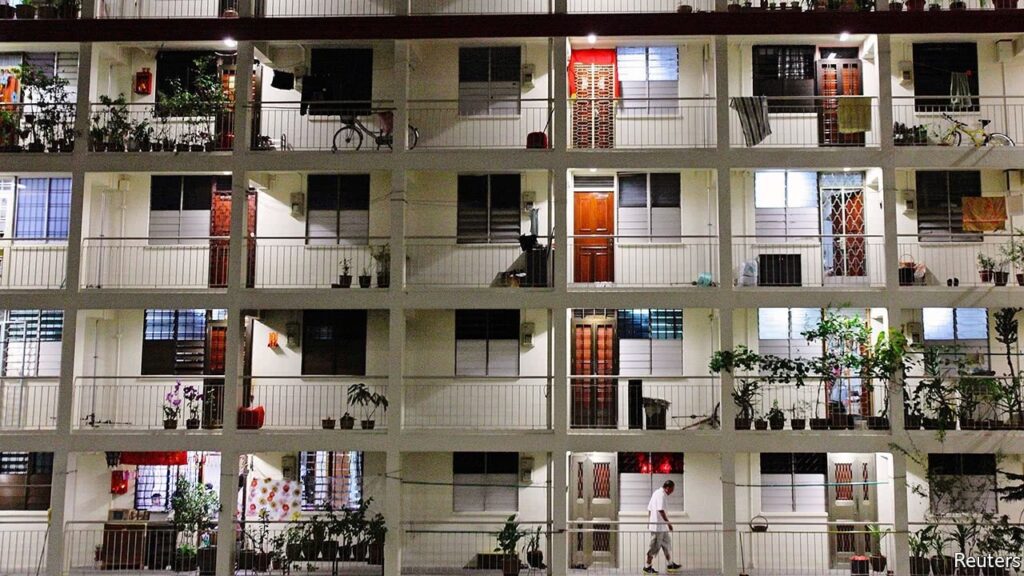

Singapore is highly regarded as one of the best planned cities in the world, boasting lush urban greenery, historical landmarks, and global economic and retail centres throughout the island. One of its strongest planning achievements is housing the vast majority of its citizens. This was made possible through the mass mobilization of public housing developments led by the Housing Development Board (HDB), Singapore’s housing department. Similar to that of the Pruitt-Igoe projects, these HDB housing projects were characterized by clusters of high-rise towers and were developed as a response to the high demand for housing. Today, over 80% of Singapore’s resident population resides in HDB housing.

While HDB housing was clearly influenced by modernist planning principles, in rejection of ornamentation and a focus on functionality, they do not fully realize these principles. For example, while these high-rise towers lack ornamentation and are developed in clusters, they introduce open balconies for ventilation, integrated accented colors onto building facades, and develop alongside concentrated public amenities, services, and programs. Herein lies the answer as to how Singapore so successfully reconciled the elements of fast development of housing, high-rise housing blocks, and social cohesion: At the country’s independence, its decision-makers, instead of abiding closely to a single set of urban principles, relied on the amalgamation of design practices that most efficiently met their vision for the island. For example, this framework combined the functionality of modernist public housing with comprehensive neighborhood planning.

While Singapore, through its HDB neighbourhoods, realized its vision of housing for all, these housing blocks have been criticized for being overly curated. It shares this criticism with modernist ideology which empowers the planner to divine status, with free reign over land use allocation and often associated with a rigid, totalitarian planning process. In the same way, while these HDB communities offer ample affordable housing and easy access to a wide range of amenities, the rigidity of the planned neighbourhoods can often eliminate the organic vibrance that comes with community-driven places.

Comfort Town, Ukraine

Comfort Town is a housing development in Kyiv, Ukraine. Made up of 180 vibrantly coloured towers arranged along a grid structure, there are clear references made to modernist city planning. These towers have minimal ornamentation, rigid fenestration and strict development footprints, not unlike the traditional modernist housing projects that surround it. Designed by the architecture firm Archimatika, the complex was a response to the depravity, corruption, and hardship associated with local life. Like Le Corbusier, this was an architectural experiment to juxtapose the current culture and introduce a better alternative to urban life. And this is where the similarities end.

Built upon an old industrial site, the architects of Comfort Town were driven by two considerations: that these structures remain economically valuable – even in time of crisis – and, most importantly, that they develop a housing project where people actually wanted to live.

First, the main design challenge for the architects was how to work within the modernist housing tower block structure while developing economic and social assets that retain, or grow, in value over time. It employed three key details that contribute to its aesthetic dynamism. Its pointed roofs and deviations in building height create a dynamic townscape while its staggered window arrangement eliminates monotony. The vibrantly colored building facades create a visual and ephemeral juxtaposition against the sea of grey it is surrounded by. These features, while seemingly trivial, contribute greatly to the character of a place and represent the richness of organic urban life.

This ties into the second factor: social cohesion and community-centered development. From its conception, Comfort Town was designed to be a place where people enjoyed living – in other words, a place that accurately serves and represents the needs of its residents. This community-centered planning framework is in stark contrast to that of classic modernism , where a place’s surrounding amenities and activities are pre-determined by the chief planner with little care put towards public input. Comfort Town’s amenities – a public park, open space, schools, retail, supermarkets – were co-designed by their residents. And while these share in Le Corbusier’s vision for self-sustaining towns, these programmatic decisions were made alongside the citizenry. This not only ensures designs are equitable but also that the residents share in a communal responsibility to foster healthy outcomes for Comfort Town.

Comfort Town successfully balances between its modernist roots, architectural dynamism, and a culture of strong community engagement. It is currently considered the most successful residential property in all of Ukraine. But despite these accolades, the development is in its early years. Only time will tell whether Comfort Town continues you to break new grounds in housing or if it is destined – like its modernist counterparts – to spiral into decline.

Concluding Statement

These three case studies portray housing projects influenced by modernist city planning, to varying degrees, and that resulted in starkly different outcomes. From the comparative analysis of these exemplars arise three key factors:

First, architectural dynamism, not ornament, is necessary. All three exemplars employ minimal ornamentation or frivolous features – a clear rejection by modernist thinkers. But where they deviate is the level of visual and experiential dynamism they introduce: Pruitt-Igoe’s grey, uniform towers, Singapore’s lightly colored and highly ventilated housing complexes, and the playful and richly colored structures in Comfort Town. It is clear that architecturally intriguing designs greatly shape our experiences – and therefore our perceptions of – our built form.

Second, governance and equity in design decisions play a critical role in ensuring each project’s viability. Pruitt-Igoe’s decisions were made by government housing officials, as part of the United State’s slum clearance program. This top-down approach involved the complete erasure of the settlements that came before it – what the program deemed as “slums” – as well as the design of spaces with minimal input from its future inhabitants. This disconnect continued through the decades of its operation all the way to its demolition. One of the most important factors leading to its decline is that it failed to reflect and support the evolving needs of its residents. Similarly, Singapore’s HDBs were designed with minimal public engagement. But its leaders thought more comprehensively about the viability of these projects, ensuring that these not only satisfied the need for housing, but for a holistic living experience. In stark contrast, Comfort Town was a genuine reflection of its community. Co-designed by residents, the neighborhoods in Comfort Town thrive in their diversity and community. It is clear that engaging the future residents of a housing development is integral to promoting positive housing outcomes.

Third, the intent behind the designs provide insight that can greatly impact the longevity and success of a housing development. Pruitt-Igoe was response to the exorbitant demand for housing in the post-war inner cities. A modernist framework accommodated for these factors because it allowed for the fast and cheap construction of ample housing units. While this approach isn’t inherently flawed, planning processes as part of developments must be multi-layered and multi-faceted. With housing as the primary, and only, consideration, the structures of Pruitt-Igoe were quickly bombarded by the social, political, and operational roadblocks that were not conceived of in the pre-design phase. This points to haphazard urban design as one of the critical factors for its decline. Singapore’s widespread HDBs were also a response to a pursuit for comfortable housing for all. This was key to the Singaporean housing experiment: comfortable housing. This meant that neighborhoods were designed to offer more than just housing but the full range of urban experience. Singapore’s decision-makers took careful thought of the longevity of these spaces, amidst a mass mobilization of housing. While most HDBs borne out of this period have been demolished or conserved, they successfully, at a pivotal time, provided critical housing while ensuring a holistic living experience for their residents. Comfort Town had the privilege of not being built primarily as a response to housing demand. While still offering ample housing, the complex was designed to provide an alternative to traditional Ukrainian living – proposing an urban experience that bolsters community connections (rejecting corruption) and celebrates the vibrancy of human life.

It is true that the modernist city planning framework is prone to misuse and exploitation by their decision-makers, resulting in disorganized and chaotic places that fail to meet the basic standard of human living. These have been misused to exert power, silence voices, and perpetuate negligence. It is clear that modernism – and other architectural movements – are wholly dependent on the political, cultural, and social contexts in which they are realized.

Despite this, one cannot label modernism and its figureheads as invalid. These principles were a product of their time and reflected society’s pursuit for improved human existence. All three case studies were borne out of critical needs being met and represent our search for truth. The architects of the 20th century, amidst global conflicts and paradigm shifts, lay the groundwork for the development of our modern-day urban centres. We, as architects and planners of today, have the privilege – and responsibility – of developing urban outcomes that look beyond basic housing but engage the wide spectrum of urban elements. We have the freedom to deconstruct and reorganize our built forms to better and more sustainably meet our needs.

About the Author

Ivanne Cheng is currently a student at the University of Sydney pursuing a Masters in Urbanism specializing in Urban Design. He wants to help shape cities towards becoming more thoughtfully designed, environmentally sustainable, and reflective of the needs of their inhabitants. He enjoys hiking, playing Smash Bros., Jiu-Jitsu, and giving his two dachshund dogs the attention they deserve.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “