Participatory Mapping Platforms for Urban Commons and Public Land Reclamation

This article explores the urban planning space where participatory mapping, urban commons, and land reclamation overlap as tools for creating a more inclusive and equitable urban environment. Participatory mapping empowers local communities to document and share spatial knowledge, democratizing the planning process and challenging top-down governance models. Through the use of digital platforms such as OpenStreetMap and Google MyMaps, users can collaboratively create real-time maps that reflect lived experiences and highlight overlooked urban dynamics. These tools lay the groundwork for reclaiming public land and redefining it as urban commons. Furthermore, the article examines how land reclamation, both restorative and generative, can be driven by community-led mapping efforts that reveal underused or degraded areas that have potential for transformation. By linking participatory mapping with the principles of the urban commons and land reclamation, the article highlights a bottom-up approach to spatial justice that promotes place-making, environmental restoration, and the co-production of shared urban spaces.

What is Participatory Mapping?

Participatory mapping gives relevant stakeholders and members within a community the ability to actively contribute towards the creation of maps through the inclusion of their lived experiences, perspectives, and relationships with urban spaces. This process democratizes spatial knowledge by shifting authority from top-down planning entities to the residents themselves, who often possess nuanced understandings of the place they inhabit. In many countries today, ensuring public engagement when shaping public spaces is not just encouraged but now required by law, reflecting a growing institutional recognition of the importance of bottom-up knowledge systems. Also referred to as ‘community mapping,’ this methodology is based on the premise that local communities possess intimate and often overlooked knowledge of their environments, information that may be difficult to extract through conventional data collection. By gathering spatial data from the ground up, participatory maps are assembled through the identification of notable features, landmarks, cultural sites, movement paths, informal economies, boundaries, and other physical and symbolic elements deemed significant by the community.

Digital mapping platforms and how they are used

Digital mapping platforms serve as powerful tools for generating, visualizing, and interacting with maps from smartphones, tablets, and computers, fundamentally transforming how spatial data is produced and shared. Participatory mapping platforms go a step further by enabling multiple users to contribute simultaneously, allowing the map to evolve in real time based on live inputs. This interactivity increases the accuracy and responsiveness of digital representations of space, ensuring that maps stay current and reflective of lived realities. Furthermore, the accessibility of these tools empowers a broad range of users, from local communities to urban planners, to engage with spatial data in meaningful ways.

Notably, platforms such as OpenStreetMap allow for open-source, global participation, while Google MyMaps provides user-friendly tools for creating and sharing customized maps. MapBox offers high customization for developers and designers, and Partimap enables survey-based participatory mapping, especially useful in planning and research contexts. ArcGIS, though often more institutional and professional, supports participatory features through tools like StoryMaps and Survey123. Together, these platforms provide the technical foundation for a more inclusive, decentralized approach to spatial planning.

Source: Website Link

Urban commons and its importance

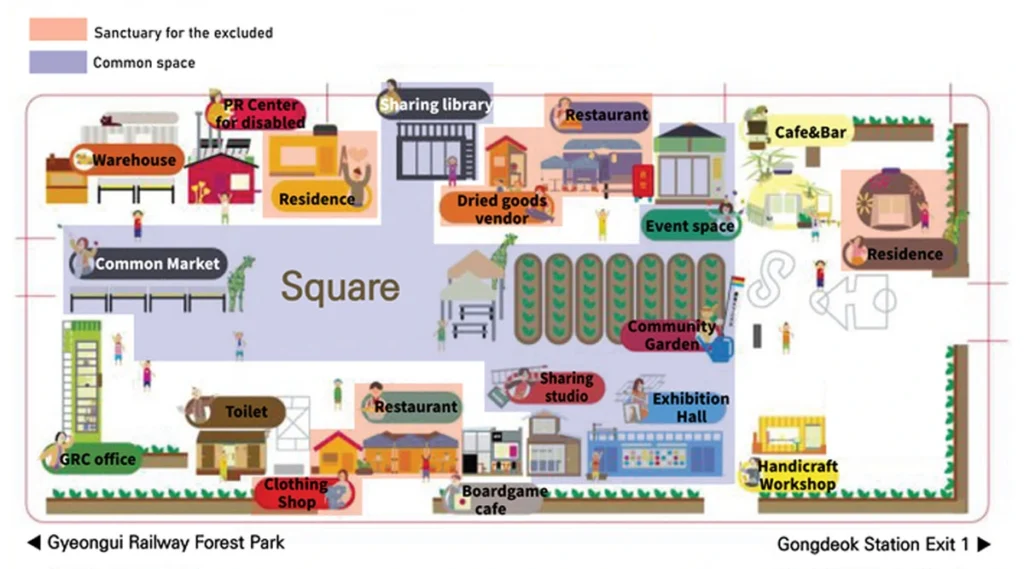

Urban commons is a conceptual framework that reimagines how cities can be collectively inhabited and governed, focusing on the shared use and stewardship of resources such as land, infrastructure, and public services. When analyzed through the lenses of community, institutions, and resources, urban commons represent a deliberate departure from both state-controlled and market-driven models of urban development. It addresses contemporary urban challenges, particularly those related to spatial injustice and inequality, by proposing that residents themselves can take an active role in managing and maintaining shared spaces. These commons-based initiatives are often born out of necessity, responding to failures in housing access, public service delivery, or infrastructure development. Through forms of self-governance, co-production, and collaborative management, communities reclaim agency over their environments. The spaces that emerge, for example, community gardens, cooperative housing, public parks, or decentralized water systems, are inherently inclusive, designed to foster social cohesion and eliminate systemic barriers to access. Importantly, the urban commons model challenges formal institutions by centring the lived needs and values of urban dwellers, promoting a more pluralistic and just urban future.

Land Reclamation: Generative and Restorative

Land reclamation is the process of restoring land that has been disturbed, often through activities such as mining. The restoration process of land reclamation focuses on allowing the environment to return to its original condition, mitigating the negative impacts of previous land use activities. Examples where land reclamation needs to take place include reclaiming pipeline corridors to establish new ecosystems and re-investing into derelict sites or past areas of industrial activities for new urban uses. Through land reclamation urban spaces can experience a boost in economic development and environmental restoration.

Beyond restoration processes, land transformation also encompasses the transformation process of coastal areas through the creation of new land, for example Palm Jumeirah, Dubai. Creating new land presents economic opportunities for urban development projects to take place.

Mapping for Commons and Reclamation

Participatory mapping acts as a foundational tool that enables the reclamation and redefinition of urban commons. By allowing communities to visualize and collaborate on their spatial knowledge, participatory mapping empowers residents to identify under-utilized land, neglected infrastructure, or ecologically degraded areas with potential for reclamation. In many cases, these mapping efforts serve as the first step toward reimagining such spaces as urban commons and becoming collectively governed and regenerated assets for community use. For instance, former industrial zones or informal settlements, once mapped and made visible through community-led efforts, can become sites for cooperative housing, public green space, or public transit systems. Similarly, mapping practices can reveal historically excluded groups and invisible boundaries, helping to democratize decision-making during the repurposing of land. In this way, participatory mapping is not only a representational act but also a political one: it challenges dominant narratives of land ownership and usage, promotes equitable access, and directly supports the practices of self-organization and place-making that underpin both urban commons and land reclamation. As cities strive to address climate resilience, social equity, and spatial justice, the integration of participatory mapping into urban planning processes becomes a strategic method for enabling bottom-up reclamation and co-managed public space.

Conclusion

With growing urban stressors, environmental degradation and pressures from top-down development practices, the convergence of participatory mapping, urban commons, and land reclamation offers a powerful framework for reimagining the future of urban environments. Together, these practices enable communities to better represent their lived experiences within their environments as well as actively shape and reclaim them. Participatory mapping acts as a technical and political tool, bringing to the forefront invisible spaces, amplifying marginalized voices, and laying the necessary groundwork for collective control of land and infrastructure. As urban commons push against political models built upon exclusive ownership and governance, and as land reclamation re-establishes degraded or overlooked spaces, the overlap presents an opportunity for strategically inclusive urban developments. Embedding these approaches into mainstream planning processes offers a pathway toward more democratic, resilient and unified cities where space is not only planned for communities, but with and by them.

References

Baviskar, A., & Gidwani, V. (2011, December 10). Urban Commons. Economic and Political Weekly. https://www.epw.in/journal/2011/50/review-urban-affairs-review-issues-specials/urban-commons.html

Denwood, T., Huck , Jonathan J., & and Lindley, S. (2022). Participatory Mapping: A Systematic Review and Open Science Framework for Future Research. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 112(8), 2324–2343. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2022.2065964

Foster, S. R., & Iaione, C. (2020, October 15). Urban Commons. Oxford Bibliographies. https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780190922481/obo-9780190922481-0015.xml

Pappa, A. (2022). RE-DWELL: Definition. Retrieved June 13, 2025, from https://www.re-dwell.eu/concept-definition/39

Park, I. K., Shin, J., & Kim, J. E. (2020). Urban Commons as a Haven for the Excluded: An Experience of Creating a Commons in Seoul, South Korea. International Journal of the Commons, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/ijc.1038

Participatory mapping | Mapping For Rights. (n.d.). Retrieved June 13, 2025, from https://www.mappingforrights.org/participatory-mapping/

Regenerative Economics—4.2.3 Urban commons and relocalisation. (n.d.). Regenerative Economics. Retrieved June 13, 2025, from https://www.regenerativeeconomics.earth/regenerative-economics-textbook/4-the-commons/4-2-spheres-of-commoning/4-2-3-urban-commons-and-relocalisation

Rzeszewski, M., & Kotus, J. (2019). Usability and usefulness of internet mapping platforms in participatory spatial planning. Applied Geography, 103, 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2019.01.001

Frederick Bottrill

About the Author

Frederick is a recent graduate from McGill University, where his academic focus was on Urban Studies and International Development. His independent research projects included exploring New Master Planned Cities and Smart City initiatives. Freddie also has experience working on urban development projects at the Norman Foster Foundation and at present is an Architectural Research intern at the Urban Design Lab.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “