Postmodernism and Urban Development

Postmodernism and Urban Development has had a profound impact, pushing back against modernist principles and introducing fresh perspectives on architecture, urban design, and city planning. By fostering diversity, contextual sensitivity, and the merging of various styles, postmodernism has enriched and added complexity to modern urban spaces. Yet, as cities grow and change, the concepts and methods of postmodernism must be reassessed to address new challenges and opportunities. Recognizing postmodernism’s role in shaping urban development helps us understand the intricacies of our urban environments and prompts us to thoughtfully consider the future of our cities. As we progress, the insights gained from postmodernism will continue to shape and inspire discussions about creating urban spaces that are not only functional but also meaningful and dynamic.

Understanding Postmodernism

Postmodernism is a broad and often ambiguous term, but at its core, it represents a reaction against the rationalism, functionalism, and homogeneity of modernism. While modernism sought to create a universal language of architecture and urban planning based on principles of order, efficiency, and purity, postmodernism celebrates eclecticism, irony, and the mixing of styles. In architecture, this shift is evident in the work of architects like Robert Venturi, Michael Graves, and Philip Johnson, who challenged the minimalist aesthetics of modernism. They reintroduced historical references, ornamentation, and a playful use of colors and forms. Venturi’s famous dictum, “Less is a bore,” encapsulates the postmodernist rejection of the modernist ethos of “less is more.”

Postmodernism’s impact on urban development is profound, influencing both the design of individual buildings and the broader planning of cities. Below are some key ways postmodernism has shaped urban development.

Diversity in Architectural Styles

Postmodern architecture breaks away from the rigid uniformity of modernism by promoting a wide variety of architectural styles, each drawing from unique cultural, social, and historical influences. This pluralistic approach allows urban environments to reflect the identities of the communities they serve, creating buildings that not only differ in style but also resonate with local traditions, values, and histories. The juxtaposition of contrasting architectural forms and materials results in a visually diverse and culturally rich urban landscape, where eclecticism is celebrated rather than minimized.

This diversity extends beyond mere aesthetics, fostering a sense of place and identity within neighborhoods and cities. Architects working within the postmodern framework often incorporate historical motifs, local architectural languages, and playful elements that challenge conventions. The results are urban environments that feel less generic, more connected to their context, and more engaging for inhabitants.

For instance, the AT&T Building (now Sony Building) in New York City, designed by Philip Johnson, stands out as a pioneering example of postmodern architecture, with its mix of modernist glass-and-steel construction and classical elements like its famous Chippendale-inspired pediment. Similarly, Charles Moore’s Piazza d’Italia in New Orleans is a whimsical blend of Italian Renaissance references with contemporary materials, creating a space that feels both familiar and entirely new.

Other notable examples include the Portland Building by Michael Graves, which challenged minimalist trends with bold colors and ornamental detailing, and the Vanna Venturi House by Robert Venturi, which rejected modernist minimalism in favor of complex forms and historical references. In cities around the world, this variety of postmodern designs contributes to urban landscapes that are more vibrant, layered, and reflective of the diverse societies they serve.

Source: Website Link

Contextualism and Sensitivity to Place

In contrast to modernist urban planning, which often applied a standardized, universal approach to city design, postmodern urban development emphasizes the importance of context—both physical and cultural. Instead of imposing a one-size-fits-all solution, postmodern architects and planners design with sensitivity to the unique characteristics of each location, recognizing the value of local history, culture, and social fabric in shaping urban spaces. This shift has led to more personalized, responsive urban environments that resonate deeply with their surroundings.

Contextualism in postmodern architecture is evident in the adaptive reuse of historical buildings, where instead of demolition, older structures are revitalized with modern additions or modifications that respect their original form. This not only preserves the architectural heritage of a place but also contributes to the sustainability of urban development by reducing the need for new materials and construction. Projects like the High Line in New York City—a former railway transformed into an elevated urban park—illustrate how adaptive reuse can create new communal spaces while maintaining a connection to the area’s industrial past.

Another hallmark of postmodern contextualism is the integration of public art and site-specific design elements that reflect local identities. Public spaces are designed not just as functional areas but as cultural experiences that encourage community interaction and express the unique character of a city or neighborhood. An example is the playful yet contextually mindful work of artist Anish Kapoor’s “Cloud Gate” in Chicago’s Millennium Park, which responds to the city’s skyline while creating an interactive urban sculpture.

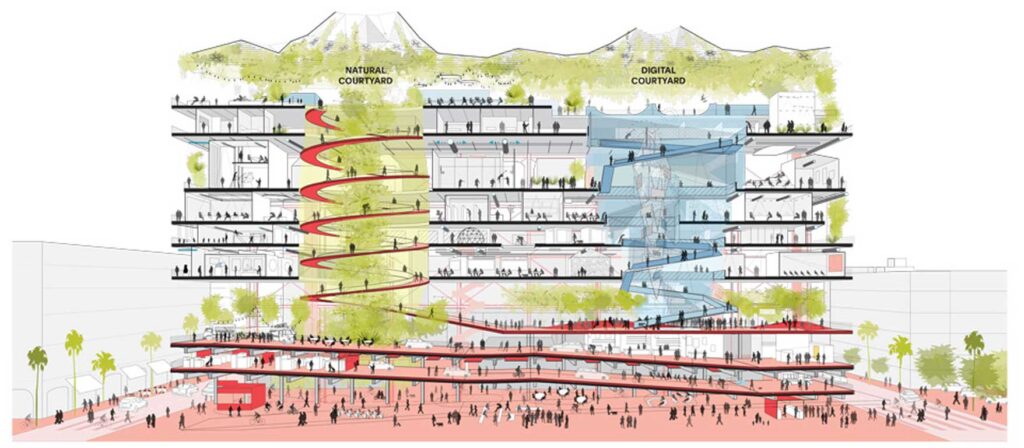

Postmodern urbanism also emphasizes the importance of human scale and the social needs of communities, designing streetscapes and plazas that foster pedestrian interaction and engagement. This often includes small-scale developments like urban villages, where mixed-use buildings, walkability, and local gathering spaces are prioritized over large, impersonal developments. The creation of these human-centered environments showcases postmodernism’s belief that urban spaces should be as diverse and dynamic as the people who inhabit them, respecting both the past and the present of each locale.

Source: author

Theming and Simulation

Postmodernism is associated with the rise of themed environments, where architecture and urban spaces are designed to evoke specific historical periods, cultural motifs, or fictional worlds. This is evident in the development of places like Las Vegas, Disneyland, and various shopping malls around the world.

Theming often blurs the line between reality and simulation, creating spaces that are as much about entertainment and spectacle as they are about functionality. This approach has both critics and proponents, with some arguing that it creates superficial and inauthentic environments, while others see it as a legitimate form of cultural expression.

However, this approach to urban design has sparked considerable debate. Critics argue that themed environments often create superficial and inauthentic experiences, prioritizing spectacle over substance and detracting from genuine cultural expressions. They contend that such spaces may foster a sense of disconnection from the true historical and cultural contexts they mimic, leading to homogenized environments that lack depth and meaning.

Conversely, proponents of themed architecture argue that these environments serve as valid forms of cultural expression, reflecting contemporary society’s fascination with narrative and escapism. They believe that themed spaces can enrich urban life by providing diverse experiences that engage people in new and imaginative ways. Theming can also foster a sense of place, drawing on local folklore, history, or art to create unique environments that resonate with visitors and locals alike.

As cities continue to evolve, the interplay of theming and simulation in postmodern urbanism raises important questions about authenticity, cultural representation, and the role of architecture in shaping our experiences. It challenges urban planners and architects to consider how to balance the whimsical aspects of themed environments with the need for meaningful and contextually rich spaces that foster community and connection.

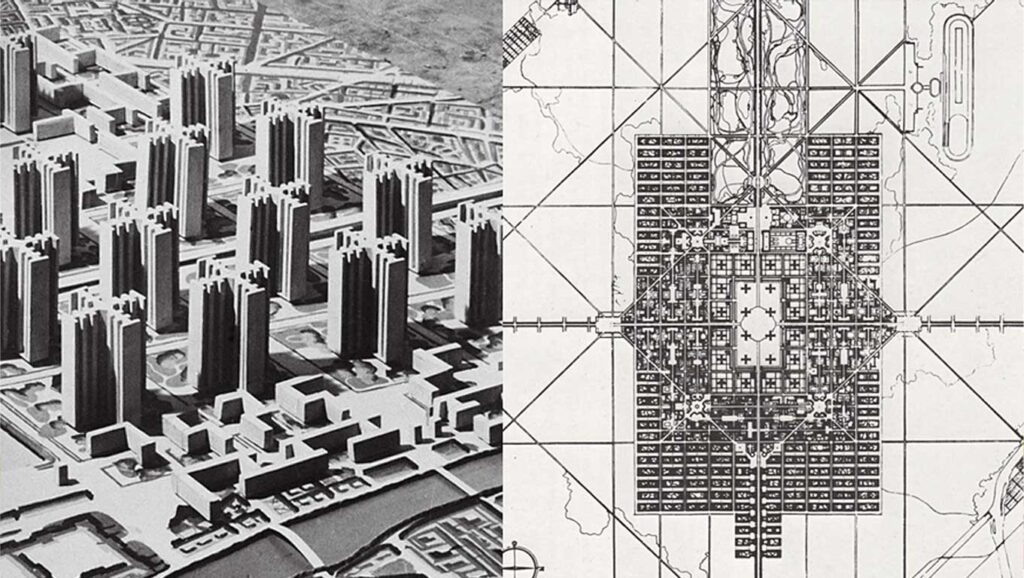

Critique of Modernist Planning

Postmodern urban development often critiques the large-scale, top-down planning approaches of the modernist era, which were sometimes seen as overly rigid and disconnected from the needs of local communities. In contrast, postmodern planning tends to favor smaller-scale, incremental, and participatory approaches that allow for greater flexibility and responsiveness.

The concept of “urban villages,” mixed-use developments, and pedestrian-friendly streetscapes are all outcomes of this shift towards more human-centered urban design.

Globalization and Localization

Postmodern urban development operates within the dynamic framework of globalization, which has significantly accelerated the exchange of architectural styles and urban planning concepts across the globe. This phenomenon has resulted in cities that showcase a diverse array of architectural forms, often influenced by international trends and innovations. As cities become increasingly interconnected, the influence of global design ideologies has shaped skylines and urban environments in ways previously unimaginable.

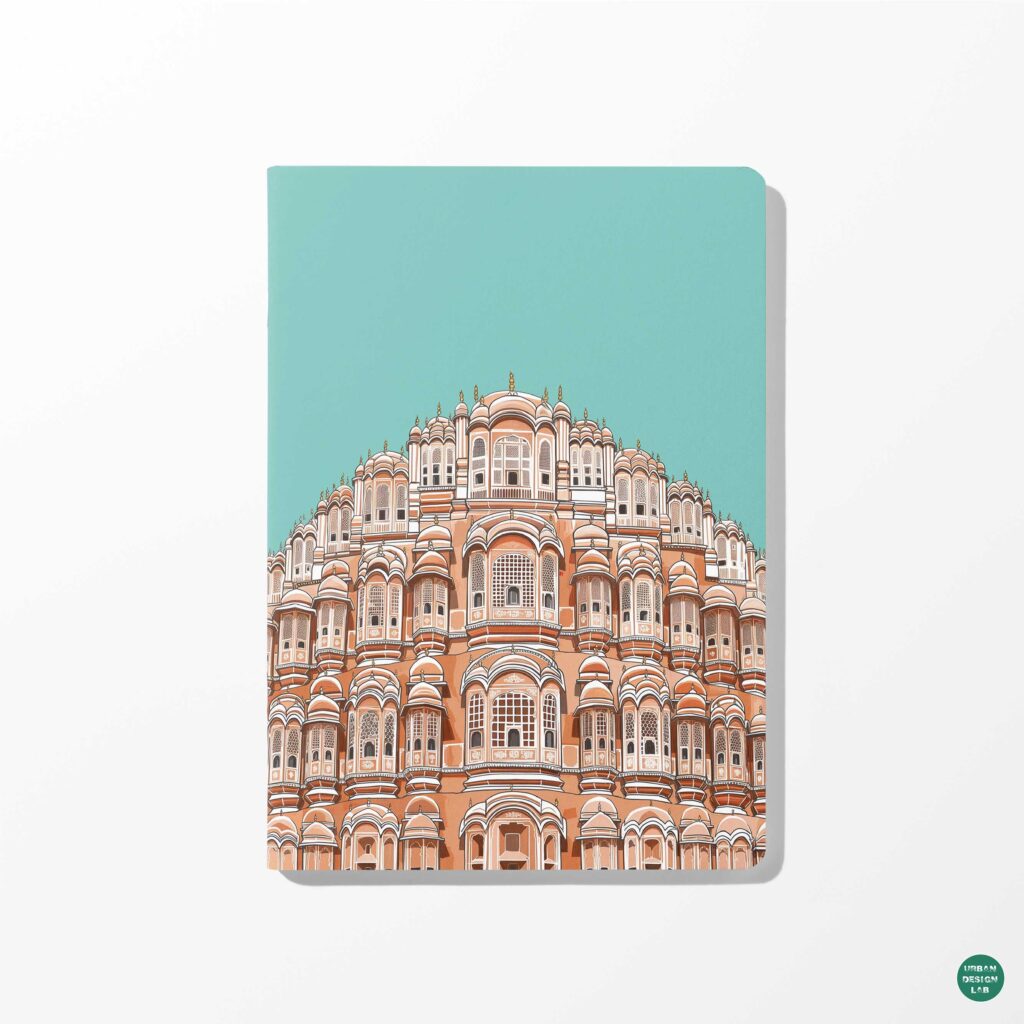

However, postmodernism uniquely emphasizes the importance of localization, advocating for the adaptation of these global influences to resonate with local contexts. This duality is a defining characteristic of contemporary urbanism, where the blend of universal architectural language and regional specificity creates vibrant, meaningful spaces. The result is an architectural dialogue that respects and reflects local culture, history, and identity, fostering a sense of belonging amidst the global backdrop.

Cities like Dubai and Shanghai exemplify this interplay between globalization and localization. In Dubai, the iconic Burj Khalifa, designed by the international firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, serves as a symbol of global ambition while incorporating elements of traditional Islamic architecture. This synthesis of modern skyscraper design with cultural motifs allows Dubai to project its identity on the world stage while remaining rooted in its heritage.

Similarly, Shanghai’s skyline features the Oriental Pearl Tower and the Shanghai Tower, both of which are emblematic of global design trends yet are deeply interwoven with the city’s unique cultural narrative. The architectural diversity in Shanghai reflects its historical evolution and its position as a global metropolis, where East meets West in striking and innovative ways.

This emphasis on localization also challenges architects and urban planners to consider how to integrate global influences while maintaining a genuine connection to the local community. This approach fosters environments that not only meet contemporary needs but also honor the narratives and traditions that define each place. By embracing this duality, postmodern urban development creates spaces that are both globally inspired and locally grounded, ensuring that cities can thrive in a globalized world while preserving their unique character and cultural heritage.

Conclusion

Postmodernism has left an indelible mark on urban development, challenging the principles of modernism and introducing new ways of thinking about architecture, urban design, and city planning. By embracing diversity, contextualism, and the blending of styles, postmodernism has contributed to the richness and complexity of contemporary urban environments. However, as cities continue to evolve, the ideas and practices of postmodernism will need to be re-evaluated in light of new challenges and opportunities.

References

- http://minisite.proj.hkedcity.net/hkiakit/getResources.html

- id=3565https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Urban-Design-in-the-Postmodern-Context-Velibeyo%C4%9Flu/1ceada361a4f4d6544addee6c952a9d36faba6e8

Mostafa Dagher

About the Author

Mostafa is a dedicated architecture student with a strong passion for art and research. His interest in architecture goes beyond design, as he enjoys exploring the theoretical and artistic aspects that shape the built environment. This blend of creativity and curiosity drives him to not only excel in his studies but also to seek a deeper understanding of how art and research influence architectural practice and theory.

Related articles

Micro-Mobility and Modular Design in Urban Living

Rethinking Urban Planning Careers in India

5-Days UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

14th-18th July 2025

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment