Re-distribution of population through Suburban migration

Urbanisation and Migration

Migration from rural to urban areas is critical to the growth of any country. In case of India, the surplus agricultural labour migrates to more productive sectors of the economy. However, the majority of migrant occupations in cities are private and do not provide welfare benefits. There is a continuous migration from rural to urban areas and the other way around. Given cities are hubs of economic, socio-cultural, and cultural activity, as well as the labour market, many individuals want to live in or near city centres. On the other side, despite the city’s dynamism and opportunities, many others prefer to avoid central locations because the area has various urban difficulties like pollution, overpopulation, traffic jam, etc. This orientation results in the formation of a new sort of settlement pattern known as suburban areas. The districts are located on the outskirts of a city and are primarily occupied by detached dwellings and gated communities. Rural areas are equally prone to becoming suburbs of major cities and becoming the target of rural gentrification (Scott, 2011).

Although urbanisation has resulted in lower poverty, job creation, and growth, the distribution of these urban gains has been uneven, with notable spatial, social, and economic inequities. The growth of cities happened on the back of rural migration in search of better employment. These cities then evolved into metropolitan areas when their population increased to more than 10 lakh. Global economists and urban planners peg the reason for further migration of the metropolitan population to the outskirts of the city – or the suburbs – to economic and infrastructure development in these areas.

The post-pandemic world

“The pandemic has sparked a major shift in purchasers’ behaviour,” says Prashin Jhobalia, Vice President, House of Hiranandani. In the post-pandemic world, there is a huge demand for big and multi-functional homes in a quiet and safe atmosphere. Buyers prefer seclusion and prefer to avoid crowded situations. As a result, independent apartments in the shape of villas, cottages, and plots meet the modern housing needs of customers, particularly those with a sufficient budget. Because of the hybrid work from home concept adopted by most corporations, the location of an apartment/property is no longer a determining factor. Buyers are willing to relocate to outlying areas with adequate infrastructure and connectivity. These gated housing developments are located far from cities and other surrounding facilities. This scenario creates a variety of issues for local governments and planning systems. Pandemics are, by definition, dependent on human interactions with their environment and with one another. These interactions can be amplified in the built environment, making epidemic control a critical topic in urban design.

Sub-Urbanization and Peri-urban areas

Suburbanization refers to the movement of people from central metropolitan areas to the suburbs, which results in the construction of urban sprawl. Low-density, peripheral urban regions expand as a result of the movement of homes and companies out from city centres. Peri-urban areas are transitional zones between rural and urban land uses found between the outskirts of urban and regional centres and the rural environment. Peri-urbanization refers to dispersive urban expansion processes that result in hybrid landscapes with fragmented urban and rural traits. A few reasons include:

1.Value of property

Cities have become more commercial as a result of foreign investment and industrialization, as well as an increase in the number of individuals moving in for commercial reasons. It is not uncommon to observe that there is diversity in real estate prices across all Indian cities, with each city’s civic government determining the guidance value of properties.

2.Advanced infrastructure

According to a World Economic Forum report by Greg Clark, a banker, and Miguel Gamino of a financial services firm, cities are shifting from a concentration on corporations, commuters, and consumerism to a focus on habitat, innovation, and experience. India’s public transportation system urgently needs to modernise its infrastructure amenities in order to provide a better and safer experience. While some metro rail connectivity projects are moving forward, there is still more work to be done.

3.Working from the suburbs

Cities that have evolved into metropolises have attracted rural residents from nearby towns and villages due to their increased development in terms of employment and housing. According to a Cushman and Wakefield analysis, just as businesses followed labour force talent into cities, some are likely to follow them to the suburbs – especially given the benefits of shorter commute times and lower rents.

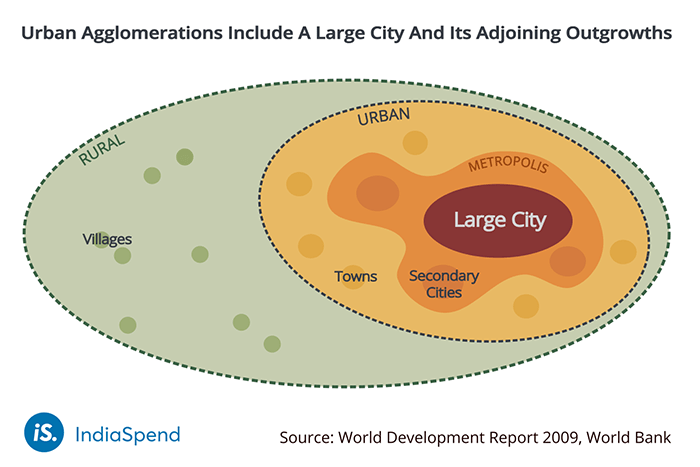

Urban agglomerations

According to the Census, urban agglomerations such as Mumbai and Delhi involve a continuous urban spread comprising a town and its bordering outgrowths (Central Railway Colony in Mumbai) more physically contiguous towns (Noida in Delhi). India’s urban agglomerations are frequently stretched across several districts, have a population of more than 7 million people, cover multiple municipal corporations, and have both an urban core and an urban periphery (peri-urban area). Based on the 2011 census, the India Migration Now analysis classified places as urban or peri-urban based on the distance to the urban core, population, the presence of a municipal corporation, the proportion of workers engaged in non-agricultural activities, and the form of urbanization.

In the Kolkata Metropolitan Territory, for example, the districts of Kolkata and Howrah were designated as urban cores because they contain municipal corporations, a large percentage of built-up area, and a low rural population. Peri-urban districts include North 24 Parganas, South 24 Parganas, Nadia, and Hugli, which have low percentages of built-up land, a significant rural population, and no municipal corporation.

Congestion of cities

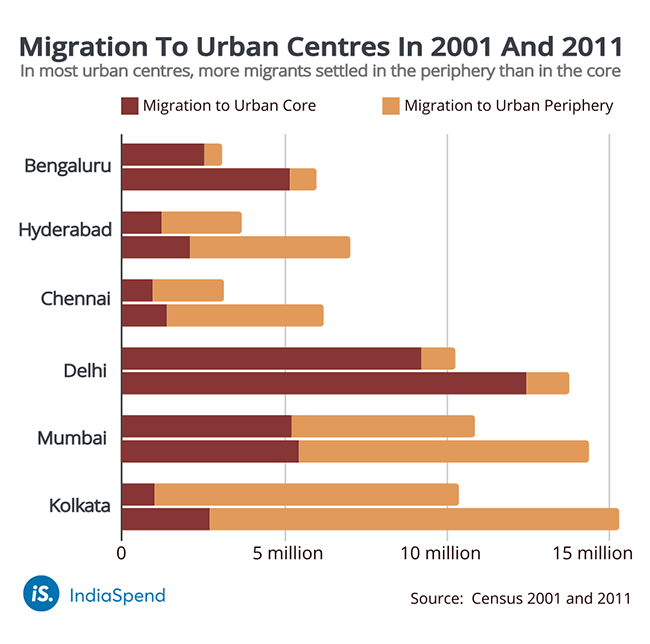

Cities house more than half of the world’s population, and this proportion is rapidly increasing. As a result, city landscapes and forms are constantly transforming, developing, and expanding horizontally and vertically. Furthermore, urban sprawl is acknowledged as a negative process because of increased CO2 emissions, increased artificial soil, landscape fragmentation in peri-urban areas, and so on (Ng, 2009). The costs imposed by this spread (such as transportation, infrastructure, and outlying areas) are critical. As a result, from the perspective of sustainable development, the densification of cities occurs. During 2001 and 2011, the share of migrants settling in the urban periphery against those settling in the urban centre was higher in Hyderabad, Chennai, Kolkata, and Mumbai. Only in two urban agglomerations, Delhi (12.5 million in the city, 1.3 million in the peri-urban) and Bengaluru (5.1 million in the city, 859,030 in the outskirts), did more migrants settle in the city rather than the peri-urban. The Bengaluru urban agglomeration is a new phenomenon that has just gradually spread beyond Bengaluru Urban into the Bengaluru Rural and Ramanagara districts. This may explain why the city has yet to reach saturation in terms of attracting migrants.

Lifestyle migration

Since moving for a better way of life is rarely covered by standard migration typologies, researchers have attempted to link their studies to broader phenomena by using overarching concepts such as retirement migration, leisure migration, (international) counter-urbanisation, second home ownership, amenity-seeking, and seasonal migration. None of these conceptualisations, however, properly capture the complexities of this trend and unite its numerous aspects. In all of these instances, research reveals a consistent narrative through which individuals make their lives meaningful (Cortazzi, 2001)– the search for a different lifestyle, a significantly better quality of life, which underpins migration. We propose that, despite the uniqueness of each instance, shared lifestyle concerns show that these various migrations can be viewed as a single phenomena – lifestyle migration.

People’s perceptions and responses to threats to their livelihoods and lifestyles are culturally mediated. They may adjust locally, or relocate as a group to a new location thought to be better and safer, or take a more measured strategy by putting a family member or two to work elsewhere and rebuilding their lives back home with remittances. The choice of employment varies, and while many work in tourism or provide services to other migrants, developments in telecommunication have expanded to limitless opportunities. Interestingly, these lifestyle migrants use their organizations to fund their new lifestyles rather than as a means to an end. For example, when asked why they moved to the Costa del Sol, small business owners prioritised climate, quality of life, and lifestyle over business potential. The fundamental emphasis remains the lifestyle choice.

The primary characteristics of the many lifestyles sought by such migrants include the better lifestyle, escape from past personal and social histories, and the prospect for self-realisation. Post-migration methods frequently involve re-negotiation of the work-life balance, sustaining quality of life, and independence from previous limitations. However, in order to accomplish and sustain their new, better lifestyles, many migrants still require money after relocation, and it is typical to find them running modest enterprises as’self-employed expatriates.’

“Tier II and III cities have seen a significant surge in demand in recent years, mostly due to accessible pricing, more space, better returns on investment, and reduced cost of acquisition, primarily for ready to move in units,” said Aakash Ohri, senior executive director, DLF Home Developers Ltd. Historical migration trends, migrant networks, and municipal infrastructure all have an impact on migrants’ destination cities. Mobility choices open up a plethora of new opportunities and innovations. However, from the perspective of environmental justice, persons who find themselves on the cutting edge of such innovations frequently have smaller carbon footprints.

Developers have also diverted to constructing houses to the outskirts of the city since the low-rise and planned complexes are less expensive to build than high-rise structures. Similarly, smaller projects will require less investment and provide higher returns because the time required to build new residences is shorter than the counterpart. This is also important in consideration of the rising demand for ready-to-move-in residences. As a result, low rises are not just in demand, but also more financially viable.

Future of migration patterns

Following up by 2030, metropolitan regions — those with a population of at least 1.5 million people — would have homes to seven out of every ten urban residents and 24 percent of the world’s population. At the same time, due to population growth and higher productivity, the greatest agglomerations’ proportion of global GDP will rise from 38 percent to 43 percent. Increased population will account for 60% of GDP growth in the major cities, with increased labour productivity accounting for 40%.

Metropolitan regions attract a large number of new residents, particularly young people. Most places have had net migration gains in recent years, despite having a relatively low demographic load (the ratio between people of working and nonworking age). On average, migration growth is higher in all these cities – 3 migrants per 1,000 people – than in countries. Most urban regions are experiencing higher-than-average population growth as a result of migration. (For a breakdown of the proportion of foreign-born people in European metropolitan areas, see Figure 20.) Most areas had a net increase in migrants between 2010 and 2015, with Beijing and Johannesburg seeing the most increases (about 14 migrants per 1,000 inhabitants).

Simultaneously, when looking at migration growth individually for metropolitan areas and core cities, migrants choose to dwell on the outskirts of metropolitan areas. Central city migration growth is substantially lower than in metropolitan areas as a whole. This is most likely why metropolitan region population growth rates exceed central city population growth rates.

This shift towards the peri-urban areas essentially brings a change in how people use their environment resulting in changes in the spatial structure of the landscape, as well as the increase in population and migration rates. Peri-urbanization is defined as the process by which a rural or village region becomes urbane in terms of physical, economic, and social factors.

Impact in India

Over the years, Indian metropolises have seen a trickle of their residents migrate to emerging suburbs. The Pandemic only exacerbated the situation. However, questions arise in the aftermath of this tremendous population increase: is suburbanisation the only answer to alleviate the strain on a metropolis that is already overburdened? Are India’s suburbs better prepared in terms of infrastructure and quality of life to accommodate this migration?

About the Author

Suksheetha Adulla is currently studying Architecture and Urban planning at Newcastle University, United Kingdom. She aspires to become an architectural designer with an intent to fuse her passion towards designing with affection towards environment and build a society in order to inspire, motivate and equip people on a greening journey with sophisticated civilization. She is a caffeine addict who loves playing basketball, reading books, and baking goodies.

Related articles

50 Architecture Thesis Ideas for the Artificial Intelligence Age

Remembering Frank O. Gehry: The Architect Who Redrew Skylines

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “