Sabarmati Riverfront – Ahmedabad Reclaims its Riverbanks for the People

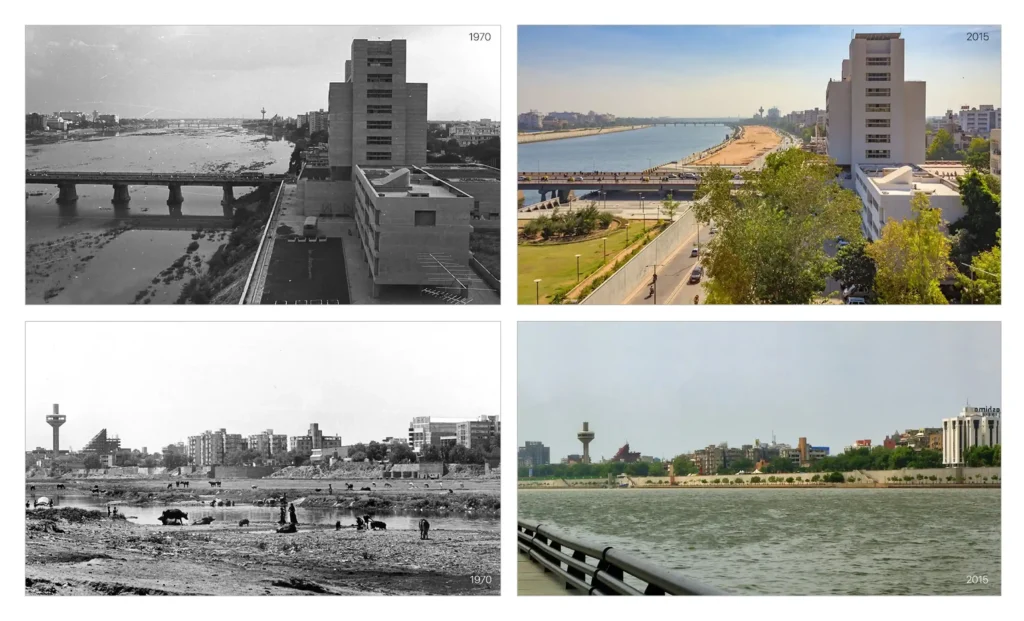

Ahmedabad’s Sabarmati Riverfront is a defining example of urban riverfront transformation in India. Once a degraded, seasonal waterway, the river has been reimagined through a bold, multifunctional redevelopment plan led by HCP Design and Dr. Bimal Patel. The 11.25 km project integrates flood control with accessible public spaces—promenades, parks, ghats, and markets—repositioning the river as the city’s social and cultural heart.

What makes the project stand out is its self-financing model, where limited land monetization funded major infrastructure. This spurred real estate growth and tourism while avoiding reliance on private capital. However, the displacement of over 10,000 residents and critiques around top-down planning raise pressing concerns about social equity and participatory design.

Environmentally, the river now flows year-round thanks to Narmada canal diversion, and interceptor lines have improved water quality. Yet critics argue the river’s natural ecology has been replaced by a controlled, artificial system.

As more Indian cities eye similar projects, Sabarmati serves as both a precedent and a provocation—demonstrating the power and pitfalls of design-led urbanism. This article offers a critical lens for urban planners, architects, and academics seeking holistic approaches to equitable, sustainable waterfront redevelopment.

From Neglect to Renewal: History of the Sabarmati Riverfront Project

The Sabarmati River, once a seasonal stream flanked by informal settlements and polluted discharges, long symbolized urban neglect in Ahmedabad. Despite visionary proposals since the 1960s, a concrete plan only materialized in the 1990s. The turning point came with the establishment of the Sabarmati Riverfront Development Corporation Ltd. (SRFDCL) in 1997 and the appointment of Dr. Bimal Patel of HCP Design, Planning and Management Pvt. Ltd. to lead the master planning effort.

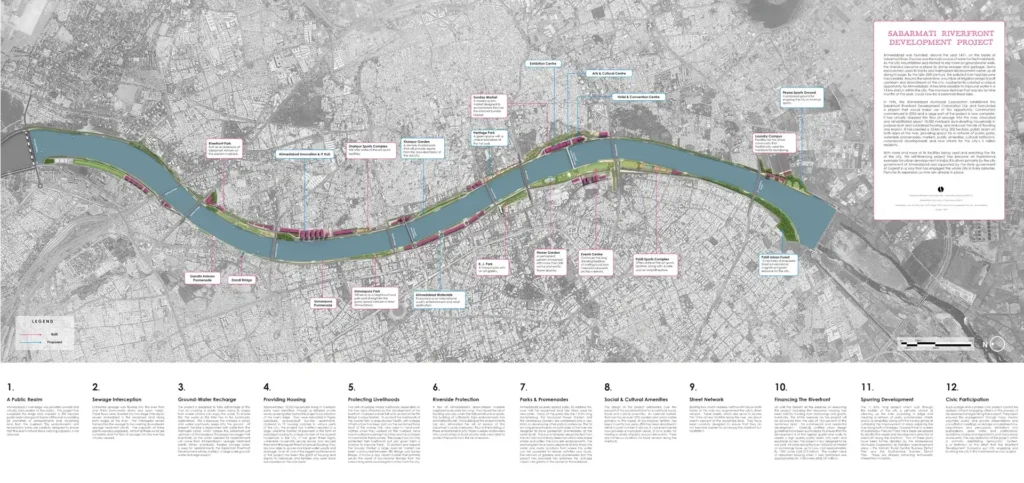

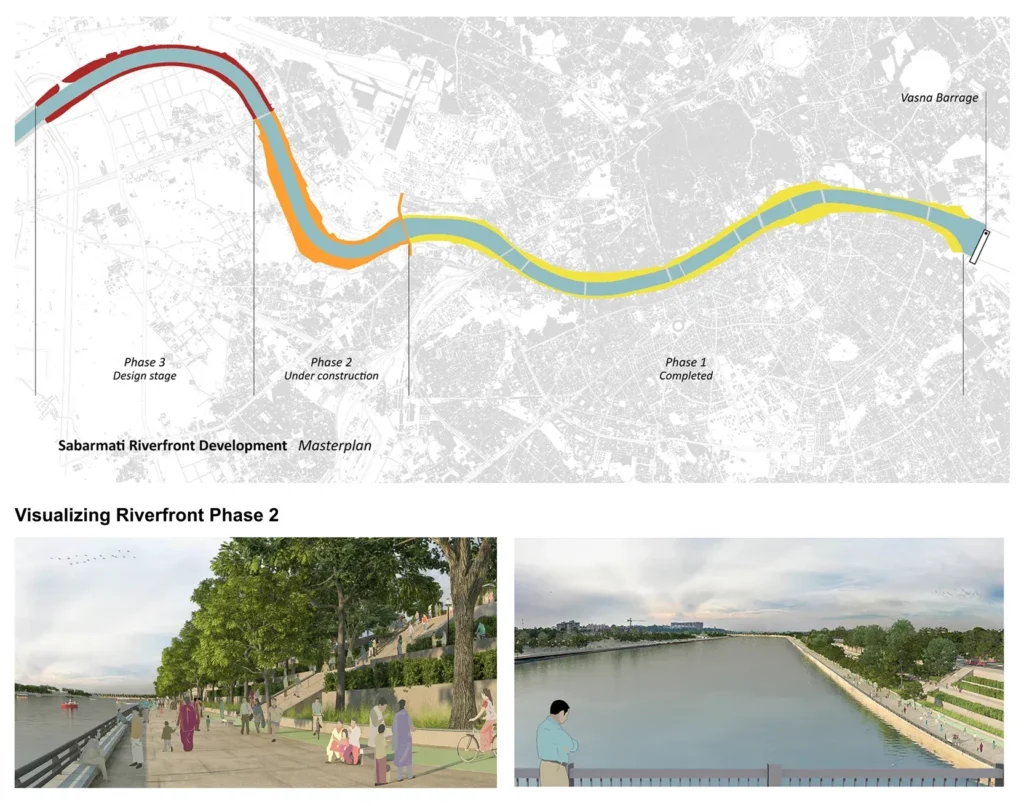

The project’s vision was ambitious: integrate flood control, reclaim riverbanks, and develop high-quality public spaces. Over 200 hectares of land were reclaimed by constructing concrete embankments and levees on both sides of the river, ultimately transforming 11.25 kilometers of riverfront into a multi-functional corridor. Importantly, this transformation was designed to be self-financed through selective land monetization—an approach that would allow public investments to fund public benefit.

The River as Public Realm

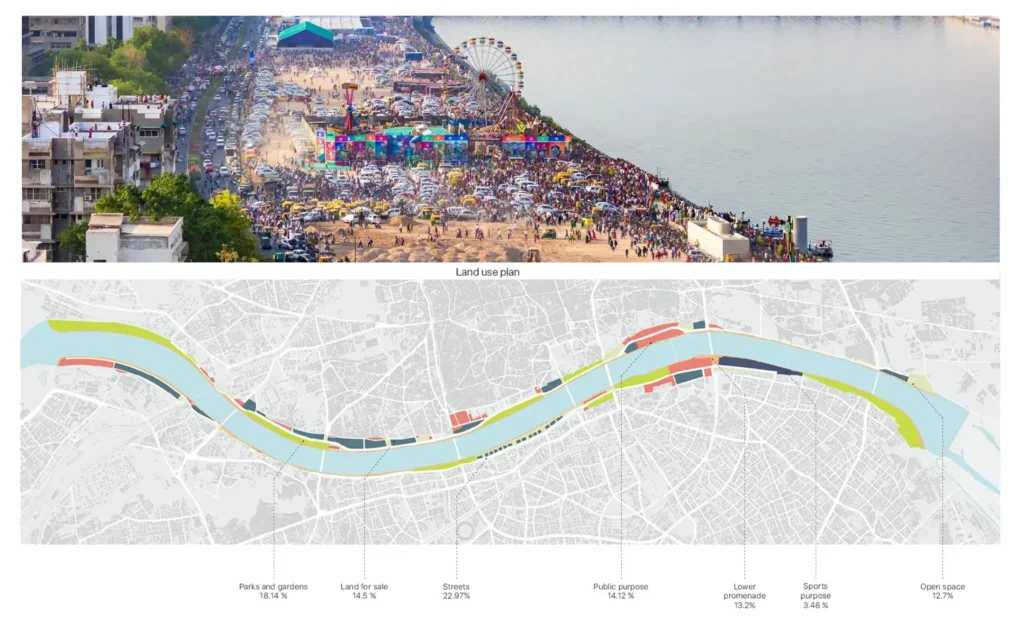

At its heart, the Sabarmati Riverfront repositions the river as a civic commons. The urban design integrates two uninterrupted promenades, cycle tracks, gardens, plazas, ghats, and open-air venues along both banks. Civic infrastructure—like sewage interceptor lines and access roads—is tucked beneath the public layer, allowing function and leisure to coexist.

Symbolic features like the Atal Pedestrian Bridge connect the historically segregated eastern and western Ahmedabad, while programs like the reintegrated Ravivari Sunday Market maintain continuity with the city’s cultural memory. Nevertheless, not all vendors were accommodated, sparking debates about spatial justice.

This spatial reprogramming exemplifies a shift from infrastructure-led development to people-centered urbanism. The project offers an example of how public realm investment can elevate civic identity without erasing vernacular urbanism—though not without compromises.

Source: Website Link

Economic Transformation: Financing the River, Revitalizing the City

One of the project’s defining features is its financial strategy. Rather than rely on external loans or PPPs, the project funded its own civic works through the commercial sale of only 14% of the reclaimed land. This allowed the city to finance promenades, embankments, and utilities without burdening the public exchequer.

The riverfront also triggered a real estate boom, especially on the western bank, where property values surged post-development. Tourist-oriented infrastructure such as cruises, gardens, and event spaces further diversified the city’s economy. Yet this value creation has skewed toward elite urban consumption. While the project is a financial success, questions remain about affordability and who can truly access and inhabit these spaces in meaningful ways.

Displacement and Social Equity

Despite its aesthetic and infrastructural success, the project’s most contentious aspect remains its displacement of over 10,000 families who had long lived along the riverbanks. These informal settlers were relocated under various schemes, but with inconsistent outcomes. While housing was offered, studies note limited access to transit, schools, and employment in new sites.

A legal review by the National Law School of India University found the project lacked transparent public participation and fell short of procedural fairness in rehabilitation. The Ravivari Market relocation, for example, was handled with top-down logic, leaving many vendors with reduced visibility and income. This tension underscores a broader lesson for urban designers: “Reclaiming for the people” must include those already living in the margins. If not, beautification can easily become displacement.

Environmental Engineering: Restoration or Repackaging?

The Sabarmati Riverfront is framed as an ecological revitalization, with perennial water now flowing due to diversions from the Narmada Canal. Sewage is diverted through interceptor systems, helping to keep the river clean, while green buffers along the riverwalk contribute to a more sustainable urban edge. The return of more than 120 bird species, alongside large-scale citizen initiatives—such as the 2025 cleanup that removed 945 tonnes of waste—signals a growing culture of environmental responsibility and collective care.

But ecologists argue the project replaced a dynamic river with a hydrological spectacle. Embankments and concrete edges have stripped the river of its floodplain, destroying its capacity for groundwater recharge and seasonal variation. While the Sabarmati now looks alive, its ecological functions have been engineered into submission. For long-term resilience, cities must rethink rivers as living systems, not just urban amenities.

Future Prospects: A Replicable Model or a One-Off Showcase?

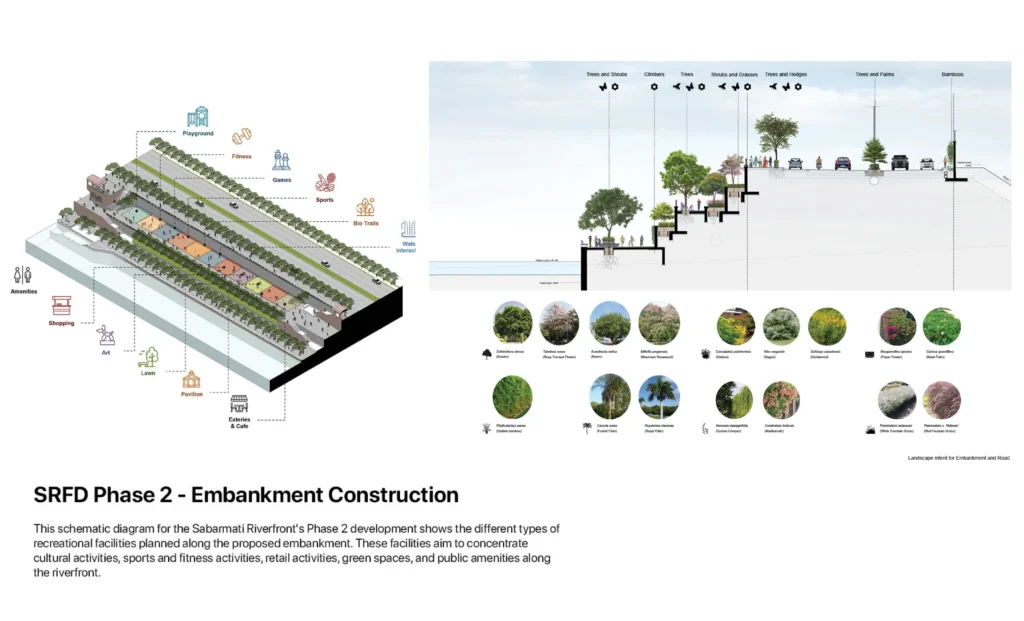

With Phase II underway—expanding cultural, ecological, and recreational zones downstream—Ahmedabad is positioning the Sabarmati Riverfront as a replicable model for Indian cities. Surat, Varanasi, and Patna are studying its mechanics. Yet transplanting the model must be context-sensitive; not all rivers require embankments or land reclamation.

The project’s success lies in its urban choreography—weaving infrastructure, public life, and design into a legible system. But its weaknesses—particularly in equity and ecology—should guide future adaptations. The Sabarmati Riverfront proves that river reclamation is as much about people and politics as it is about engineering and design. True success will lie not in replication, but in reimagining each river on its own terms.

Conclusion

The Sabarmati Riverfront stands as a powerful symbol of India’s evolving urban ambition—one where civic space, infrastructure, and identity converge. It showcases how strategic planning, design-led thinking, and institutional innovation can reframe neglected geographies into active urban cores. Yet, it also underscores the complexities embedded in large-scale transformations: displacement, ecological simplification, and questions of inclusivity are not peripheral concerns—they are central to a truly just urban future.

For urban planners and designers, Sabarmati is not just a project to replicate, but a process to dissect. Its success lies not in its aesthetics alone, but in its ability to provoke critical conversations about what cities prioritize and for whom they build. Reclaiming a river is ultimately an act of reimagining the public, and Ahmedabad’s riverfront—both its achievements and contradictions—reminds us that equitable design must always reach beyond the embankments.

References

- Bhatt, B. (2017). Waterfront development: A case study of Sabarmati Riverfront. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315825242

- Bhatt, C. (2016). Reclaiming the Sabarmati Riverfront. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0473-1

- Dempsey, N., Velarde, C. L. M., Samuel, M., Bakshi, Y., & Baradi, M. (2020). From river to riverfront: Cultural change in the Sabarmati project. Town Planning Review, 91(6), 643–666. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2020.89

- Desai, D. (2022, November 4). The Sabarmati story: A river is more than a usable resource. Question of Cities. https://questionofcities.org/the-sabarmati-story-a-river-is-more-than-a-usable-resource/

- ET Infra. (2022, April 4). Sabarmati Riverfront phase 2 to finish by 2027. https://infra.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/urban-infrastructure/2nd-phase-of-sabarmati-riverfront-development-to-be-completed-by-2027/90638195

- Gupta, S. (2018). Urban riverfronts: Public good vs. private gain. In Urban revitalization and development finance (pp. 275–295). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2138-1_22

- HCP Design, Planning and Management Pvt. Ltd. (n.d.). Sabarmati Riverfront project. https://hcp.co.in/urbanism/38

- Joshi, A., & Maheshwari, N. (2016). The Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project: The issue of resettlement and rehabilitation. Socio-Legal Review, 12(2), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.55496/nfnt6945

- Rethinking The Future. (2021, January 16). Sabarmati Riverfront by Bimal Patel. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/case-studies/a2887

- Shah, K., & Andhare, U. (2013, May 24). Sabarmati Riverfront: Much needs to change. DNA India. https://architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-166149

Kevina Althea Wijaya

About the Author

Kevina is a graduate of Architecture from Sepuluh Nopember Institute of Technology. Her interests lie in spatial design, urban environments, and the intersection between architecture and human behavior. Through her design research and creative explorations, she investigates how built environments can foster inclusivity, well-being, and adaptive living.

Related articles

Top 10 Most Livable Cities in the World

How the High Line Transformed Public Space in New York City?

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “