The New Urban Experiments: From NEOM’s The Line to Floating Cities

Cities worldwide are experimenting with new urban models to address urgent challenges like climate change, population growth, and outdated infrastructure. This article highlights three significant examples shaping future urban thinking: NEOM’s The Line in Saudi Arabia, the Maldives Floating City, and Indonesia’s Nusantara Capital City. Each project reflects a different approach to reimagining urban life. The Line proposes a hyper-dense, linear city free of cars, powered by renewable energy, and managed by AI to achieve maximum efficiency and sustainability. In contrast, the Maldives Floating City and Oceanix Busan offer climate-resilient, modular solutions for communities at risk from rising seas, prioritizing ecological harmony and adaptability. Nusantara positions itself as a smart forest city, integrating environmental stewardship with Indonesia’s national identity and ambitions for sustainable governance.

Beyond these specific cases, the article explores how experimental urban governance is reshaping city-making, emphasizing collaboration among governments, private sectors, and communities. It draws on urban foresight principles, suggesting that cities must move beyond static plans and embrace adaptability, scenario thinking, and ongoing innovation. Together, these urban experiments signal a global shift toward more resilient, sustainable, and inclusive cities capable of navigating the uncertainties of the 21st century.

Introduction: Why Urban Experiments Matter Now

New urban experiments are increasingly vital as cities face escalating challenges tied to climate change, population growth, social inequality, and aging infrastructure. These experimental projects offer innovative pathways to rethink urban living by testing bold ideas, technologies, and governance models in real-world settings. Whether addressing environmental sustainability, resource management, or mobility, urban experiments serve as laboratories where cities can adapt, learn, and transform in response to rapidly evolving needs and global pressures (Evans et al., 2016; Felson & Pickett, 2005). Projects like NEOM’s The Line, floating cities in the Maldives and Busan, and Indonesia’s Nusantara Capital reflect a growing global effort to prototype future urban solutions. Such experiments enable cities to move beyond “business as usual,” offering space for trial-and-error learning, collaborative innovation, and policy evolution. They provide opportunities to explore new forms of urban governance, rethink infrastructure, and prioritize inclusivity and environmental stewardship. In an era where urban resilience is key to national futures, these pioneering developments help shape models of compact, adaptive, and sustainable living. By pushing the boundaries of conventional planning, urban experiments illuminate how cities might not just survive the 21st century, but thrive within it.

NEOM’s The Line: A Vision of Hyper-Compressed Urban Living

At the heart of Saudi Arabia’s ambitious NEOM megaproject, The Line represents a bold reimagining of how cities could function in the future. This linear city stretches 170 kilometers through the desert, measuring only 200 meters in width, and offers a radically new urban geometry focused on efficiency, sustainability, and technology-driven living. Designed to operate entirely without cars or traditional streets, The Line is organized into three distinct layers: a pedestrian-friendly surface, a service level for daily needs, and an underground spine for high-speed transit and autonomous vehicles. All energy will be sourced from renewable resources, supporting a zero-carbon footprint. Artificial intelligence will manage city infrastructure, utilities, and mobility systems, ensuring optimal efficiency and sustainability. Within this compact structure, residents will have access to schools, healthcare, workplaces, and recreation, all within a five-minute walk, promoting health, well-being, and social interaction. As a key component of NEOM’s broader mission to diversify Saudi Arabia’s economy and drive urban innovation, The Line aims to establish a global benchmark for future cities, offering a visionary blueprint for sustainable, technology-integrated urban environments designed to harmonize with nature (Madakam & Bhawsar, 2021; Paszkowska-Kaczmarek, 2021).

Source: Website Link

Floating Cities: Adaptive Urbanism for a Sinking World

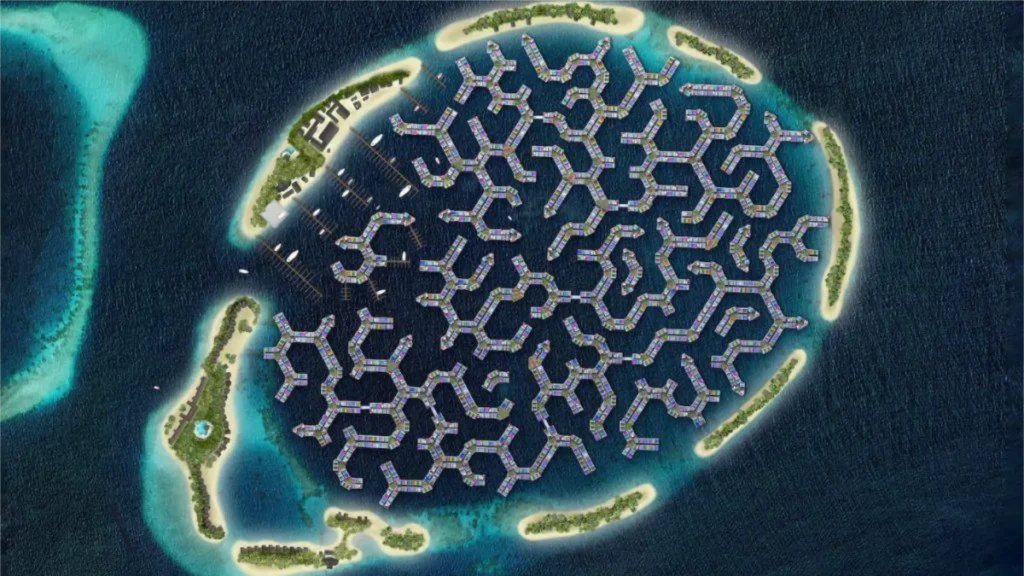

As sea levels rise and low-lying coastal areas face mounting risks, floating cities are emerging as experimental responses to climate displacement. In the Maldives, Dutch Docklands and Waterstudio are building the Maldives Floating City, designed to house up to 20,000 people in a modular, coral-inspired layout. Approved in 2022, it floats in a 200-hectare lagoon and integrates low-carbon technologies, green energy, and marine ecosystem restoration, transforming a climate-vulnerable nation into a climate innovator. Similarly, in South Korea, Oceanix Busan, a project backed by the UN and designed by Bjarke Ingels Group, is testing a scalable, self-sufficient floating neighborhood. Built on interconnected platforms utilizing Biorock (a material that strengthens over time while supporting marine life), the project integrates housing, farming, and research within a closed-loop system. Both cities reject conventional land-based urbanism in favor of buoyant, resilient infrastructure that adapts with the ocean (Bridger-Lippe, 2023; Nelson, 2022). While still in early phases, they represent a shift toward decentralization, ecological integration, and modular governance. If successful, these prototypes could provide blueprints for coastal nations worldwide, not just to survive climate change, but to reimagine city-making on water.

Ecological Model City: Nusantara and the Forest Capital Vision

Indonesia’s new capital, Nusantara, is one of the world’s most ambitious attempts at state-led sustainable urban development. Designed by Urban+ under the concept Nagara Rimba Nusa (“City, Forest, Archipelago”), Nusantara aims to embody harmony between government, nature, and people (Urban+, 2019). Rooted in the philosophy of Tri Hita Karana, the design prioritizes environmental stewardship, social well-being, and spiritual balance. The city integrates green infrastructure, with 65% of its area allocated to protected forests, wetlands, and ecological corridors. Its urban form reflects national identity through civic landmarks like Pancasila Lake and Plaza Bhinneka Tunggal Ika. Housing, education, healthcare, and innovation districts are planned with compact, connected communities that emphasize walkability and public transportation. The government promotes Nusantara as a smart forest city with AI-powered services and autonomous transit, aiming for 80% of mobility through non-private vehicles (Academic Paper for the Nusantara Capital City Bill, 2020). Yet, despite its green image, questions remain over environmental impact, indigenous rights, and long-term viability. Positioned as a model of sustainable development and decentralized governance, Nusantara reflects both Indonesia’s ambitions and the challenges of creating a future capital in the heart of Borneo’s rainforest.

Experimental Urban Governance: Who Designs the Future City?

The future of urban design is no longer solely in the hands of governments or planners. Instead, experimental urban governance embraces collaboration across multiple actors: municipalities, private firms, academia, and citizens, who come together to test new ideas in real-world settings (Kronsell & Mukhtar-Landgren, 2018). Cities today act not just as regulators but as facilitators of innovation, creating platforms where new models of mobility, sustainability, and public services can be trialed. Initiatives like urban living labs and experimentation zones allow cities to experiment with policies, technologies, and designs on a smaller scale before wider adoption. This hands-on, participatory approach encourages more agile, data-driven, and inclusive city-making. Citizens play a growing role too, shaping urban futures through participatory design and feedback loops, aligning with broader shifts toward human-centered urbanism (Bulkeley et al., 2018). Yet, challenges remain: balancing innovation with public accountability, ensuring inclusivity, and integrating these experiments into long-term planning frameworks. As cities become more complex and interconnected, experimental governance offers a promising route to navigate uncertainty, but it must keep public value and transparency at its core.

Between Vision and Reality: What Can We Learn?

The rise of experimental urbanism reflects a broader shift in how cities think about the future, not as a fixed destination but as a landscape of possibilities. As highlighted by recent scholarship on urban foresight, traditional urban planning, rooted in static visions and historical precedents, often fails to keep pace with the complexity and unpredictability of modern cities. Today’s urban environments are better understood as open, networked systems, shaped by dynamic social, environmental, and technological forces. In this context, forward-thinking cities are moving beyond rigid master plans toward adaptive, scenario-based approaches that embrace uncertainty. Urban foresight encourages planners and policymakers to explore multiple futures through tools like scenario planning, real-time data analysis, and flexible stakeholder engagement, recognizing that the most resilient cities are those prepared for change rather than those that cling to certainty. These methods align closely with the experimental urban projects discussed earlier, where adaptability, modularity, and innovation take precedence over permanence (Istenič & Zrnić, 2022). As cities evolve in response to climate risks, technological disruption, and shifting demographics, the capacity to navigate complexity and adjust strategies over time is emerging as a core principle of future-ready urbanism.

Conclusion

The urban experiments explored here, NEOM’s The Line, floating cities, Nusantara, and the governance models that support them, offer more than just bold visions of future cities. They represent a growing recognition that the cities of tomorrow cannot be built on outdated models. Instead, they must embrace adaptability, innovation, and a willingness to rethink how we live with one another and with our environments. These projects are not without challenges, but their ambitions reflect a necessary shift: moving from static blueprints to living systems capable of evolving alongside the uncertainties of the 21st century. As climate risks intensify, populations grow, and technology reshapes how we interact with our surroundings, cities must serve not only as centers of efficiency but as places of resilience, inclusivity, and hope. While no single project offers a universal solution, together they expand our imagination of what urban life can be. In doing so, they remind us that the future of cities will be shaped not by inevitability, but by the choices we make and the experiments we are willing to try.

References

- Academic Paper for the Nusantara Capital City Bill. (2020).

- Bridger-Lippe, R. (2023). Maldives Floating City: Climate innovators at work. Ubm Magazin. https://www.ubm-development.com/magazin/en/maldives-floating-city-climate-innovators-at-work/

- Bulkeley, H., Marvin, S., Palgan, Y. V., McCormick, K., et al. (2018). Urban living laboratories: Conducting the experimental city? European Urban and Regional Studies, 26(4), 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776418787222

- Evans, J., Karvonen, A., & Raven, R. (2016). The experimental city (pp. 1–12). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315719825-1

- Felson, A. J., & Pickett, S. T. (2005). Designed experiments: New approaches to studying urban ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 3(10), 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2005)003[0549:denats]2.0.co;2

- Istenič, S. P., & Zrnić, V. G. (2022). Visions of cities’ futures. Urbani Izziv, 33(1), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2022-33-01-05

- Kronsell, A., & Mukhtar-Landgren, D. (2018). Experimental governance. European Planning Studies, 26(5), 988–1007. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1435631

- Madakam, S., & Bhawsar, P. (2021). NEOM smart city: The city of future. In Handbook of Smart Cities. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15145-4_86-2

- Nelson, T. (2022). 7 surprising facts about the world’s first floating city. Architectural Digest. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/surprising-facts-worlds-first-floating-city

- Urban+. (2019). Nagara Rimba Nusa, Ibu Kota Negara Indonesia. https://www.urbanplus.co.id/project/nagara-rimba-nusa-ibu-kota-negara-indonesia/

Muhammad Zeyd Arhan Juan Ramadhan

About the Author

MZAJ Ramadhan is an emerging urban researcher with a strong interest in sustainable futures, climate resilience, and ecological urbanism. His academic work explores the intersection of climate change, urban resilience, and urban design, with a particular focus on the solarpunk movement. With a background rooted in design thinking, he aims to bridge the gap between visionary concepts and practical applications in urban design and planning.

Related articles

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

5 Comments

Posts like this are why I keep coming back. It’s rare to find content that’s simple, practical, and not full of fluff.

This gave me a whole new perspective on something I thought I already understood. Great explanation and flow!

This was very well laid out and easy to follow.

Very relevant and timely content. Appreciate you sharing this.

I really appreciate content like this—it’s clear, informative, and actually helpful. Definitely worth reading!