Turning Migrant Workers into Citizens in Urbanizing China

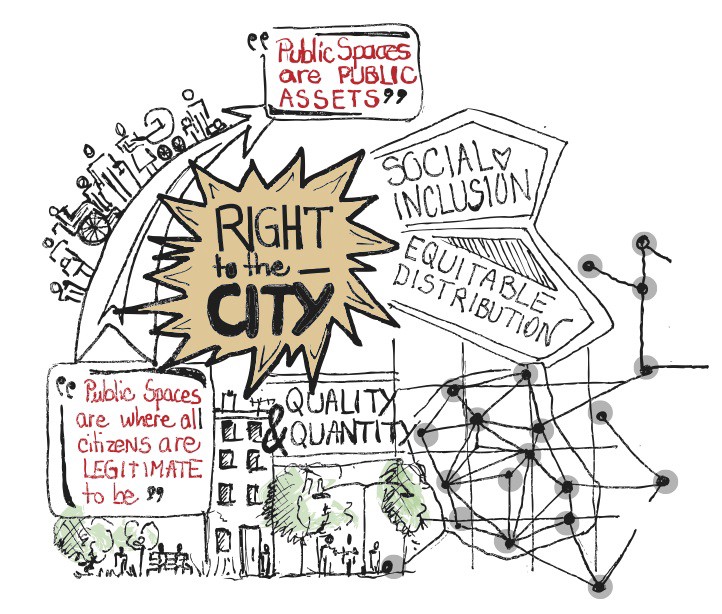

One of the root causes of inequity is urban and rural differentiation

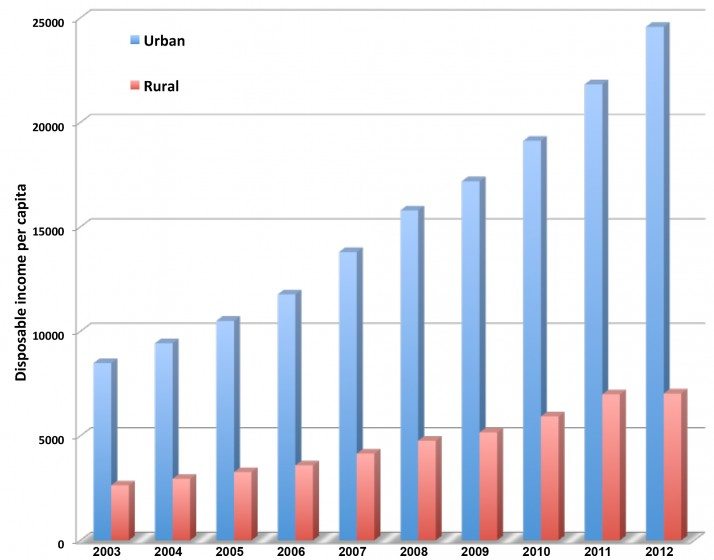

China is experiencing a massive migration to the cities, mostly due to the availability of jobs and better facilities. But the way the government administers citizenship also creates inequity and poverty. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the country has adopted an administrative system of dualistic rural and urban structure in order to promote industrial development and to guarantee food security of what was then a poor nation. The Chinese central government prioritizes urban development over rural development. Rural and urban areas carry out and implement different mechanisms of land ownership, housing, household registration and social welfare policies. Compared to the rural areas, many more resources are concentrated into urban districts, including public services, investment and labor forces. This drives huge disparities of employment and well-being, and results in the relative poverty of non-urban areas.

With the rapid urbanization in China, millions of farmers leave the land each year for urban jobs. But because they are not allowed to have registered permanent urban residence status—called HUKOU—their residency remains in their original territory; these migrant workers and their families can’t enjoy facilities and services as the non-migrant urbanites do, including social insurance and health care. This has caused inequity, poverty and the potential for social instability in many Chinese cities. Migrant rural children in urban areas do enjoy free schooling, in theory. But the opportunity costs for attending school for rural children are higher than for urban children. For example, the price of rent for an urban house rent and living expenses are usually unaffordable for them.

“Citizenization” of migrant workers is critical to address the Chinese urban justice problem. It is, in essence, the equalization of basic public services for migrant workers, which include stable employment opportunities, full coverage of social insurance and medicare, education, municipal services, affordable housing and ecological and environmental safeguards. Only by achieving this can migrant workers enjoy the same facilities and services as their urban counterparts do, and thus become actual citizens of the city. This is a big challenge given the huge amount of money needed and the enormous population involved. The Chinese central government realizes this issue and puts citizenization at the top of its agenda in its New-Type of Urbanization Plan, which requires local governments to solve the problem through innovative practice. Chongqing municipality demonstrates a good case of citizenization of migrant workers.

Innovation and reform of supporting policies

There’s a whole set of issues related to citizenization of migrant workers. How to solve the financing problem? Where to accommodate them? And so on. It is estimated that the citizenization cost for one-household migrant workers in Chongqing is 80,000CNY (12,600US$), and each year, thousands of farmers move into the city. This means huge amounts of capital demand and housing needs. To solve these problems, Chongqing has taken creative actions in reforming supporting policies.

Creation of a Land Ticket system and household registration reform: In China, rural property belongs to farmers collectively, while urban property is owned by the state. Rural land transactions between farmers and urbanites is prohibited. Nowadays, rapid urbanization has created new demands: the government needs money and land to citizenize migrant workers; farmers want to take full advantage of their only asset: the land; and food security should be guaranteed for a growing urban population.

In response to the new situation, Chongqing government created a system called Land Ticket, or DiPiao in Chinese, allowing proper rural land to be sold on the market. Vacant rural collective land can be reclaimed and reclassified as arable land. Such arable land (“proper land”) can be sold on the market. For this arable land, farmers receive a Land Ticket for the same land size, which can be sold in the primary land market. Property developers buy the Land Ticket (and its land quota) and certain construction is allotted to them within the urban construction areas. Farmers get 85 percent of the land sales revenue [1]. This system is beneficial to both the government and the farmers. In the last three years, Land Tickets worth 17.5 billion CNY (2.78 billion US$) have been transacted in Chongqing.

Chongqing’s household registration reform is China’s largest in scale, influencing over 10 million people [2]. Its features are: (i) lower requirements to become registered permanent urban residents, and (ii) a comprehensive package of social benefits. In addition to HUKOU, the government offers social welfare, medicare, education, affordable housing and vocational training for the migrant workers; this reform effort also (iii) safeguards farmers’ rights by retaining their homestead in the country, so that they can return home if they no longer want to stay in town; (iv) and gives consideration to urban carrying capacity by promoting the reform incrementally, and with a spatial balance (migrants are guided to distribute in new towns/districts, county towns and central urban areas)[3]. From 2010 to 2014, 4.09 million migrant workers became registered urban residents [4] in Chongqing.

Affordable housing and regulation:In most Chinese cities, housing is one of the main influencing factors of urban justice. Due to unsuccessful regulation policies, the housing price to income ratio has reached high levels. It is difficult for low-income groups to meet housing demands through market means. In recent years, Chinese local governments began to push affordable housing programs required by the central authority. Chongqing is a good example of how to control soaring prices and offer affordable housing to those in need.

Source

Among the four municipalities directly under the central government (the other ones are Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin), Chongqing’s housing prices are the lowest, thanks to its successful regulation policies. Chongqing’s program is: (i) Real estate investment is controlled below 25 percent of the total fixed-assets investment every year; (ii) Land prices are strictly managed so as not to exceed one-third of the housing price; (iii) Property tax is only introduced for larger houses; (iv) Examine and approve urban planning in accordance with the national standard for housing area of 30m2 per person; (v) Each year, affordable housing areas must be about 30 percent of the total floor space completed [5]. Because of these policies, Chongqing is able to keep the housing price to income ratio at about 6.5:1, which can be affordable for ordinary Chongqingners.

Creation of a compact city and walkable communities

Physical planning can promote spatial distribution of resources in a fairer manner through even and compact distribution of public facilities and services, convenient living and working environments, and walking-friendly communities. This is not always available to all in Chinese cities, especially to the low-income groups.

Clustered development and compact urban form: Chongqing’s urban layout features clustered development with multiple centers, which is determined by its mountainous location. Compact and mixed land use strategy is applied within each growth center. Compared to scattered layouts, compact urban forms reduce development costs, promote fair and efficient use of facilities, minimize energy use, decrease greenhouse gas emissions, and reduce urban sprawl.

In Chongqing, clusters are divided by impenetrable natural barriers or mandatory natural protection areas, or green belts. (i) Construction within green belts between clusters is strictly prohibited by law and urban planning regulations; (ii) Rules promote high density development surrounding each cluster center, and strengthen its service functions, so as to form a centripetal development force [6]; (iii) The form arranges mixed functions of residential, business and office facilities within walking distance from dwelling places to public transit, reducing repetitive transportation needs; (iv) Business, work and frequently used areas are arranged in the surroundings of public transit [7]; (v) Centers focus on public transit centers as hubs to carry out the organization of urban clusters and community layout, taking comprehensive consideration of the integral spatial layout of transportation, work and living facilities.

Source: http://www.cqyz.gov.cn/web1/info/view.asp?id=3888

Walkability and equity: As a way of transportation, walking has social, economic, environmental and public health implications. The relationship between walkability and urban equity reflects in three aspects: (i) walkable communities strengthen interpersonal communications, and cultivate common sense of belonging [9]; (ii) public amenities of walkable communities are accessible to people from all walks of life; (iii) walking reduces private motorized transport, prevent unchecked urban sprawl and decrease social segregation.

In a mountainous region such as Chongqing, the task of building walkable communities becomes all the more difficult. Chongqing has undertaken the following efforts: (i) Integrating the walking/non-motorized transport facility construction/renovation projects with other larger projects like urban renewal, new town/district building, environmental improvement, ecological reconstruction and historical preservation; (ii) Small blocks and narrow road networks are planned within the communities, to form a highly social space of human scale, enhance urban vitality and diversity, and promote walking friendliness; (iii) Active engagement of the general public/relevant stakeholders in the renovation process by conducting field survey to understand the pedestrian behavior, interviewing local residents to know their real needs, and monitoring the after-renovation usage to evaluate the implementation effect; (iv) Exploring low cost and small scale renovation patterns, such as adding street furniture along the sidewalks, coloring the pavement as safety reminder, and improving sidewalk paving to increase connectivity.’

Towards a just city: suggestions

In the rapid development of urbanization, Chinese cities, in particular, need to successfully deal with the relationship between efficiency and equity. The above paragraphs show Chongqing’s efforts in tackling urban equity problems from institutional and spatial perspectives. Building a just city is a long and complicated process.

From my personal observation of Chinese cites, I would like to give two more suggestions:

- Professionals from NGOs or other civil organizations should participate in the examination and approval, and supervision of urban plans. In Chinese cities, investors/developers and government officials usually have the power to influence urban plans. In order to protect public interest, professionals (such as urban planners, architects and engineers) from recognized third-party organizations, who have no personal interest, should be involved in the making, amendment, and supervision of urban plans.

- New towns and new urban districts should be built on demand, and provide accommodation for migrant workers. A just city is one in which everyone has access to affordable housing, in China’s urban migrant communities this is not the case. Developing new towns and new urban districts is very popular in today’s China: 92.9 percent of the prefectural level cities have proposed plans to build such. Local governments invest huge amounts of money in it. The current scale of new towns/new urban districts in China is already enough to accommodate 3.4 billion people!The problem is: some new towns/urban districts are only for the high-to-medium classes, as most residential buildings are luxury houses that affordable only to the rich. So on one hand, migrant workers can’t find proper accommodation in cities. On the other, many new towns/new urban districts become ‘ghost towns’ with very few residents.So in order to build a just city, I would like to strongly suggest that new towns/ new urban districts accept migrant workers as their formal residents.

Author:Pengfei Xie, Beijing

Program: Urban Design and Social Justice

Publisher:The Just City Essays is a joint project of The J. Max Bond Center, Next City and The Nature of Cities.

Year: 2015

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “