Vauban Eco District Freiburg as a Model for Sustainable Urban Regeneration

The Vauban Eco-District in Freiburg, Germany, presents an internationally acclaimed urban regeneration model grounded in ecological resilience, spatial justice, and participatory governance. Masterplanned by architect Rolf Disch and initiated in the late 1990s, Vauban represents a critical synthesis of environmental stewardship, social inclusivity, and adaptive reuse, transforming a decommissioned French military barracks into a benchmark for climate-responsive and community-led urbanism. This case study critically assesses the district through the lenses of sustainability, spatial integration, and social equity, offering a scientifically grounded and context-sensitive critique of its design logic, governance models, and urban impacts.

Introduction to Vauban Eco-District

The Vauban project commenced as an adaptive reuse initiative, repurposing a post-Cold War military zone into a sustainable urban neighbourhood. This transformation exemplifies post-industrial land reclamation where brownfield sites are reimagined through ecologically conscious design and democratic planning. Initiated in 1998, the 38-hectare site was envisioned as a compact, car-free, and self-sustaining community, aligning with Freiburg’s wider climate agenda and the principles of Agenda 21 (City of Freiburg, 2020).

Source: author

Sustainable Design Principles

A foundational pillar of Vauban’s urban sustainability lies in its rigorous application of Passivhaus standards, which underpin the district’s energy-efficient building envelope design. By mandating high-performance insulation, airtight construction, and heat-recovery ventilation, these standards drastically curtail thermal losses, thereby reducing dependency on active heating and cooling systems. This not only aligns with the principles of environmental resilience but also ensures long-term economic viability through diminished energy expenditures. The integration of PlusEnergy homes, an innovation by Rolf Disch, elevates this framework further—demonstrating a net-positive energy performance where buildings produce more renewable energy than they consume, particularly through extensive photovoltaic integration. This establishes a model of decentralized energy autonomy, reducing systemic reliance on fossil fuel infrastructure and reinforcing urban climate mitigation strategies.

Complementing this energy-centric approach is Vauban’s deployment of green building techniques, which operationalize sustainability across the material and construction spectrum. The use of low-embodied energy materials, responsibly sourced timber, and environmentally benign construction methods exemplifies the district’s commitment to ecological urbanism. Practices such as low-impact site development, permeable paving, and on-site waste sorting systems enhance not only the material sustainability of the built environment but also the district’s circular economy potential. These integrated design decisions reflect a deliberate shift away from extractive construction logics towards regenerative urban processes, positioning Vauban as a replicable exemplar in the global discourse on sustainable spatial transformation.

Source: Website Link

Social and Community Impact

Vauban’s participatory planning process is a defining feature that foregrounds procedural equity in urban development. Unlike conventional top-down planning models, Vauban engaged future residents as co-creators from the earliest design stages, institutionalizing deliberative democratic practices within urban governance. The establishment of citizen cooperatives and planning forums enabled localized decision-making, ensuring that spatial outcomes reflected the lived realities and preferences of its inhabitants. This model not only fostered a profound sense of collective ownership but also enhanced the long-term social sustainability of the neighbourhood, as community members became stewards of both physical infrastructure and social cohesion (City of Freiburg, 2020). Such bottom-up frameworks challenge the hegemonic paradigms of developer-led urbanism and affirm the value of community agency in shaping inclusive urban futures.

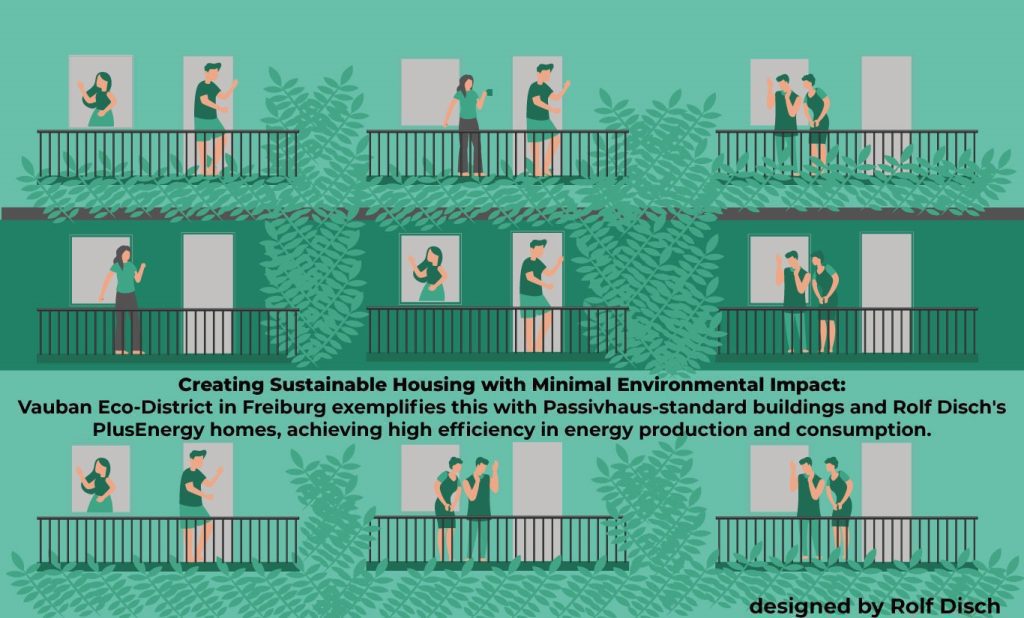

Furthermore, Vauban’s commitment to social inclusivity and quality of life is deeply embedded in its spatial configuration and programmatic diversity. Through a deliberate mix of housing typologies—ranging from co-housing units and subsidized apartments to private residences—the district accommodates varied socio-economic groups, thereby resisting gentrification and fostering social heterogeneity. Public spaces such as communal courtyards, playgrounds, and shared green areas are strategically integrated to catalyze informal interactions and strengthen social capital. These spatial interventions, paired with accessible amenities and pedestrian-prioritized design, cultivate a high standard of everyday life. The emphasis on well-being-oriented urbanism, with abundant opportunities for leisure, community building, and outdoor engagement, positions Vauban not just as a sustainable district, but as a lived model of equitable and health-enhancing urban form (Disch, 2019).

Source: author

Environmental Contributions

Vauban’s environmental strategy exemplifies an integrative ecological framework wherein green infrastructure is not merely aesthetic, but functionally embedded within the urban fabric to support biodiversity, microclimatic regulation, and social well-being. The district’s extensive network of green spaces—including linear parks, communal gardens, and ecological corridors—cultivates a semi-natural habitat matrix that sustains urban flora and fauna while enhancing residents’ quality of life. These spaces serve dual roles: providing ecological services and acting as socially inclusive commons that foster human-nature interaction, aligning with landscape urbanism theories that advocate for the performative role of open space in urban ecosystems (City of Freiburg, 2020). Such planning foregrounds environmental resilience as a core determinant of urban habitability.

In parallel, Vauban’s water-sensitive design and carbon mitigation strategies reflect a systems-based approach to environmental planning. Through decentralized rainwater harvesting and stormwater attenuation mechanisms—such as permeable paving, bioswales, and greywater reuse—the district reduces pressure on municipal infrastructure while promoting circular water use. These interventions, when coupled with energy-positive housing stock conforming to Passivhaus and PlusEnergy standards, yield a demonstrable reduction in operational carbon emissions. Importantly, the district’s modal shift to non-motorized mobility underscores a behavioural transition in low-carbon living, reinforcing the interdependence of built form, infrastructural innovation, and resident lifestyle. Vauban thus presents a compelling case for embedding sustainability at the intersection of environmental design and everyday urban practice.

Source: author

Economic Viability and Replicability

Vauban’s economic model is underpinned by long-term cost efficiency and decentralized financial participation, reinforcing the principle that environmental sustainability and economic prudence are not mutually exclusive. By embedding Passivhaus and PlusEnergy standards into its architectural typologies, the district ensures substantial reductions in energy demand and operational expenses, translating into lower utility costs for residents. These savings contribute to financial resilience at the household level, while also reducing the need for extensive energy infrastructure investments. This economic dimension of Vauban’s design demonstrates the viability of lifecycle cost planning as a strategic tool in sustainable urbanism (Disch, 2019).

The project’s financial architecture, grounded in mixed-source funding, further amplifies its replicability. Vauban’s development was made possible through a synergistic blend of public-sector support, private investment, and cooperative ownership—an approach that democratized access to housing and embedded financial agency within the community. Models such as Baugruppen (building collectives) not only minimized speculative real estate practices but also cultivated a sense of stewardship among residents. While this collaborative funding model has proven effective in Freiburg’s political and cultural context, its transferability hinges on localized governance frameworks and civic capacity. Nonetheless, Vauban remains a globally cited precedent in the sustainable urban planning discourse, offering a replicable template for cities aiming to align ecological goals with inclusive economic frameworks (Daseking & von Winning, 2003; City of Freiburg, 2020).

The Vauban Eco-District in Freiburg exemplifies a groundbreaking approach to sustainable urban development. Transforming from a former military base into an environmentally conscious community, the project has successfully integrated principles of sustainability with social inclusivity and economic viability. By adhering to Passivhaus standards and PlusEnergy principles, Vauban has set a benchmark for energy-efficient and renewable energy-powered living. The participatory planning process, involving both residents and local government, has fostered a strong sense of community and ensured that the development meets the needs and aspirations of its inhabitants. This innovative model addresses environmental challenges and enhances the quality of life for its residents, demonstrating that sustainable urban living can be both practical and prosperous. Vauban’s success serves as an inspiring example for future urban developments, illustrating the potential for similar projects to achieve a balance between ecological stewardship, social equity, and economic sustainability.

- City of Freiburg. (2020). Vauban: Sustainable Model District. Retrieved from https://www.freiburg.de/pb/,Lde/231873.html

- Disch, R. (2019). PlusEnergy: The Solar Settlement in Vauban. Renewable Energy Journal, 23(4), 15-30.

- Daseking, W., & von Winning, A. (2003). Freiburg: Vauban District. In Sustainable Urban Development: European Case Studies.

Yaren Apaydin

Yaren Apaydın is an urban planner with expertise in ecological cities and urban design. Known for her creativity and engagement, she values continuous growth and exploration. Specializing in cultural anthropology and urban planning, Yaren believes productivity and creativity lead to true happiness.

Related articles

Building Healthier Cities: The Power of Biophilic Design

The Sustainable Urban Development Reader by Stephen Wheeler

Top 10 Lake Revitalization Case Studies

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

3rd-4th May 2025

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “