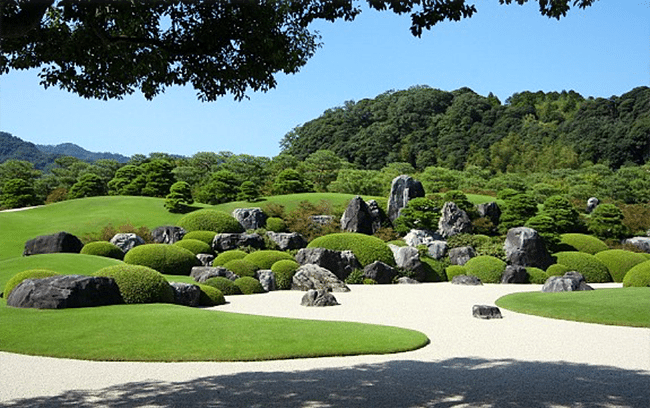

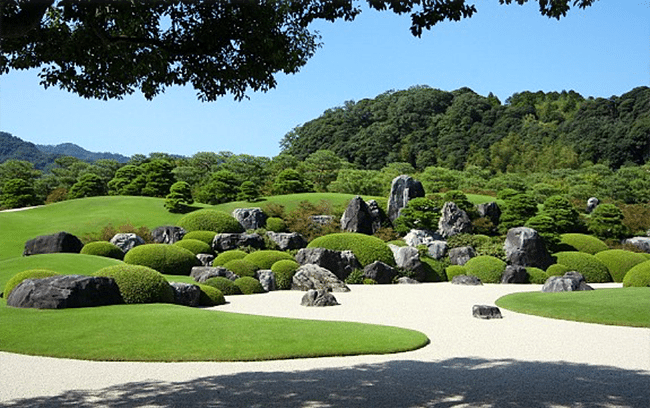

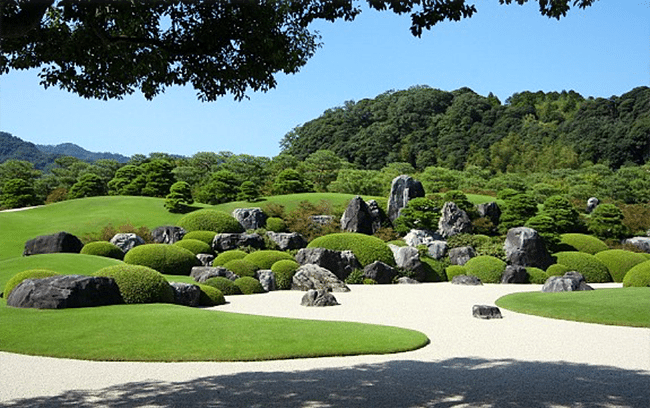

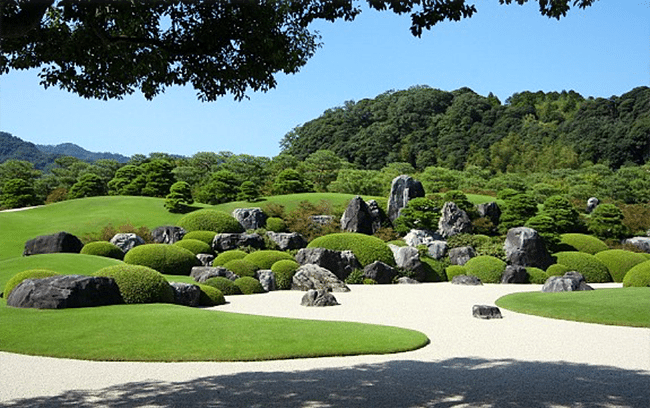

Zen gardens, often known as Japanese rock gardens, are popular among those who enjoy highly regulated settings of raked sand or pebbles and properly manicured bushes. Zen gardens stress naturalness (Shizen), simplicity (Kanso), and austerity (Kanso) (koko). In Zen Buddhism, creative practices such as Zen gardens play a leading role in their contemplation and understanding skills. Zen gardens appear outside Buddhist temples in the 11th century. In the 13th century, Zen gardens were an integral part of Japanese life and culture. The sole purpose of the garden is to provide a place for monks to meditate on the teachings of the Buddha. The garden is built and maintained to encourage meditation.

The design of the Zen garden plays an important role in the symbolism of Zen Buddhists. For example, sand or gravel symbolize water. When the monk rakes the exterior, it creates a wavy texture that rivals the waves in the ocean. Larger rocks found in sand or gravel are said to represent seashores. Because the sea is kaleidoscopic yet unified, it plays a greater role in Zen Buddhist symbolism.

The Zen Garden will also feature a tombstone representing the centre of the world. Other smaller stones are placed around the central stone to represent Buddha, worship, animals and children. When a Zen garden includes other natural elements such as trees, water, plants, fish, etc., it can demonstrate the philosophy that inconsistency is part of life. The different elements brought together in one place symbolize this philosophy. The shrines found in Zen gardens symbolize the place where spirit and human are united. Zen has a long history and Zen Garden is very charming. From studying Dharma to practicing Dharma through meditation in a beautiful Zen garden, everything is imbued with symbolism. Each garden is diverse and designed to inspire harmony, tranquillity and meditation. However, it is left to the audience of the garden to gather their respective meanings. A Zen Garden is a sacred place to meditate on the teachings of the Buddha, whatever that means to the viewer. Each individual garden has a different meaning to the viewer than it does to the gardener. This allows the garden to truly serve its purpose, which is meditation through reflection and reflection. The Zen Garden is a magnificent manifestation of how aesthetics play an important role in Zen and its meditative practice.

Japanese gardens are famous all over the world for their beauty, complexities, and depth of meaning. Garden construction has become a significant cultural art form in and of itself, serving as a source of national pride for the Japanese people as well as a source of delight for everyone who visit Japan.

The style and design, like any other art form, were significantly affected by the dominant ideas and politics of the time. Japanese gardens have evolved into a range of designs and served a number of purposes during the previous 1000 years, from strolling gardens for the pleasure of feudal lords during the Edo era to dry stone gardens utilized for religious meditation reasons by Zen monks.

Sacred spots in the midst of nature were one of the oldest garden types in Japan, which humans marked with pebbles. Prior to the introduction of Chinese culture to Japan, this early garden style may be seen at several ancient Shinto shrines, such as the Ise Shrines, whose temples are surrounded by vast pebbled areas.

From the sixth century onwards, the incorporation of Chinese culture and Buddhism had a significant impact on the design of Japanese gardens. Gardens were established in imperial palaces for leisure purposes, namely for the emperor and aristocrats’ enjoyment. Ponds and streams, which attempted to recreate tiny replicas of famous landscapes, were frequently focal areas. They incorporated various Buddhist and Taoist aspects into its design, which mirrored these ideas.

During the comparatively calm Heian Period, the capital was relocated from Nara to Kyoto, where elites spent much of their time pursuing the arts. They began to construct Shinden Grounds at their palaces and villas, enormous gardens utilized for lavish celebrations as well as recreational activities such as boating, fishing, and general enjoyment. The Shinden Gardens were extensively described in the classic tale Tale of Genji. The gardens, which were inspired by Chinese notions, included enormous ponds and islands connected by arched bridges over which boats might travel. For entertainment, a gravel-covered plaza in front of the structure was used, and one or more pavilions extended out over the water. Ritsurin Garden (above), which dates from 1625 and is not a Shiden Garden, has several Heian Period characteristics.

Political authority in Japan passed from the aristocratic court to the military class at the start of the Kamakura Period. Military rulers embraced newly adopted Zen Buddhism, and the ruling class’s dominant philosophies switched from consumerism and recreation to a disciplined mindset. Zen Buddhist concepts would have a significant impact on garden design. Gardens were no longer developed as extensions of aristocratic courts, but rather as attachments to temple buildings to aid monks in meditation and religious advancement rather than for leisure purposes. Gardens also got smaller, simpler, and more minimalist, while preserving many of the previous characteristics, such as ponds, islands, bridges, and waterfalls.

The Karesansui Dry Garden, which uses just rocks, gravel, and sand to symbolise all of the garden’s features, was the most severe step toward minimalism. They continued to strive to represent famous landscapes, but water is represented by the arrangement of rock formations to make a dry cascade (karetaki) and by patterns scratched into sand to create a dry stream (karenagare). The gardens’ monochrome aspect was purposely akin to ink monochrome landscape paintings, particularly those from the Chinese Northern Song dynasty, due to their absence of flowering vegetation (960-1126). The gardens, like the 2D paintings, are meant to be viewed from a single, sitting perspective, a far cry from the wandering gardens of leisure that came before them.

Tea gardens (Chaniwa) had already developed in previous periods, but they achieved their pinnacle during the Azuchi-Momoyama Period, when modern tea masters polished and perfected their design. They were imbued with the “wabi” or rustic simple character for which they are known today. Tea gardens are often modest and functional, with a stepping stone walk going from the entrance to a tea house. Stone lanterns were utilized for lighting and decorative components, while a wash basin (tsukubai) is used for ritual cleansing. There are many tea gardens in Japan nowadays, albeit many of them are incorporated within bigger garden designs.

During the Edo Period, garden design deviated from the Muromachi Period’s simplicity as the ruling elite rediscovers its taste for grandiose design, consumption, and relaxation. As a result of this shift in culture, several enormous walking gardens with ponds, islands, and artificial hills were created, which could be admired from a variety of viewpoints along a circular circuit. Many strolling gardens also featured aspects of simpler tea gardens, as well as the usage of huge boulders, which had been handed over from the Muromachi period. The regional feudal lords built strolling gardens in their hometowns as well as at their secondary homes in Edo (current day Tokyo). As a result, strolling gardens may now be found in old castle towns and around Tokyo.

During the Meiji Period, Japan experienced tremendous modernization and Westernization, and many western-style city parks were constructed. Many of the previously private strolling gardens were made public. Previously pushed by aristocratic, military elite, Buddhist monks, and feudal samurai lords, the creation of new gardens is today driven by politicians and industrialists.

New private strolling gardens with western gardening components like flower beds and large open lawns. Many of these gardens, such as the Kiyosumi Teien in Tokyo’s new capital, were established. The relationship between cities and Japanese gardens dates back to the Japanese garden’s inception. The center of Nara’s historic capital was inhabited by gardens that used Chinese landscaping skills to invent original Japanese elements in the eighth century. According to documents and excavational surveys, Kyoto had many gardens once the capital was relocated there during the Heian period (794-1185). In addition, some gardens from the Kamakura period (1185-1333) can still be found in Kyoto City today. It goes without saying that gardens and architecture are inextricably linked. Gardens, like architectural styles and towns, have evolved alongside them. While there have been numerous Japanese gardens established in cities, there have also been those built in Zen temples at the foot of mountains. Nonetheless, all Japanese gardens share a common essence.

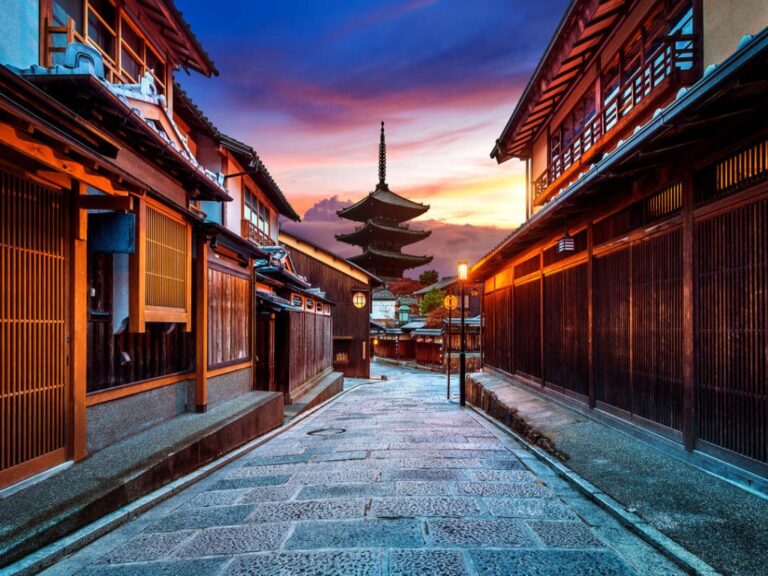

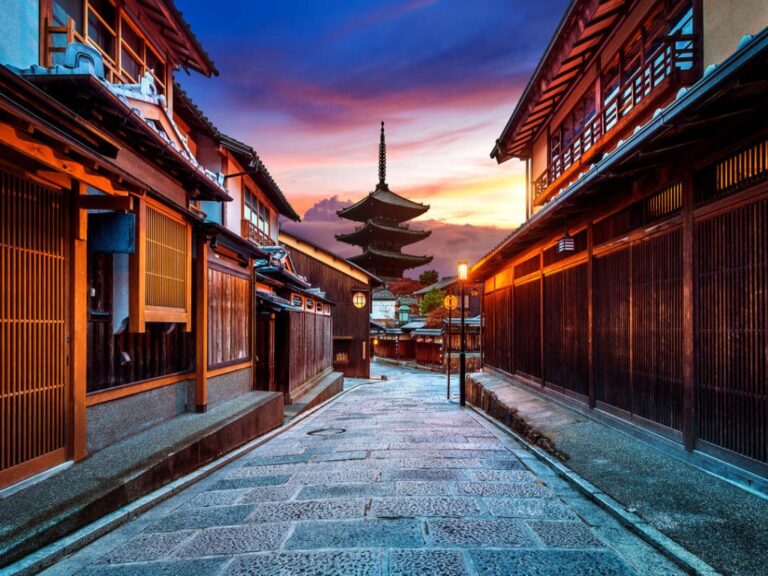

Kyoto, whose name is synonymous with the struggle against global warming, is experiencing the effects of climate change firsthand as the moss in its famed gardens dries off. The historic capital of western Japan hosted the 1997 negotiations that resulted in the Kyoto Protocol, a major United Nations convention that for the first time legally required reductions in carbon emissions blamed for global warming. But, long before the treaty, Kyoto was famed for another kind of greenery: a landscape dotted with hundreds of antique temples, shrines, and castles, the gardens of which are claimed to be in sync with the seasons.

Over the past 70 years, average temperatures in the city have risen by more than 2°C, while drizzling rain has been recorded only once or twice a year, compared to 70 days in the early 1960s, according to Oishi. Many temples in Kyoto, he claims, have imported moss from other regions.

“But that’s not the best solution,” he explained. “If we do not take great care of moss, we will lose an essential aspect of Japanese culture.” However, the cost would be more than symbolic. According to city officials, 48 million tourists, largely domestic, visit Kyoto each year, spending $637 billion (US$6 billion). Kyoto gave origin to several important features of Japanese culture, including the tea ceremony, flower arranging, kimonos, kabuki theatre, and geishas. “The scenery and wildlife in Kyoto are key assets for the Kyoto economy,” said Katsuhito Nakano, chief analyst at the Bank of Kyoto’s Kyoto Research Institute. Autumn colours, another beautiful attraction in Kyoto, have also been affected by climate change, with leaves turning bland rather than vivid red, according to studies.

Global warming frequently conjures us images of its most extreme and frightening consequences. Many of us, understandably, are concerned about lethal heatwaves and increasing sea levels. However, climate change produces additional consequences that are more subtle but still harmful. Agriculture and other businesses in Japan will be particularly hard hit. In some circumstances, this means that staple Japanese crops will be harmed. In other cases, it may imply a shift in the places that are most suited for producing specific crops. Regardless, climate change is presenting Japan with new difficulties to which it must learn to adapt.

The most serious challenges for agriculture are harm caused during production and a drop in product quality. Higher heat, for example, might cause fractured grains in rice, which break apart more easily during milling. In some places of Japan, the heat can also reduce yields. Hotter temperatures harm fruits in a variety of ways, including sunburn and dis-colouration. Climate change is also threatening animal goods, as it reduces the amount of viable cow’s milk, as well as beef, pork, and poultry.

The effects of climate change vary by region and can even differ within the same country. Japan is no exception. Rising temperatures also entail a shift in the locations suited for growing specific crops. Northern Honshu is well-known for its apple production, but a three-degree increase in temperature might make

The relationship between cities and Japanese gardens dates back to the Japanese garden’s inception. The center of Nara’s historic capital was inhabited by gardens that used Chinese landscaping skills to invent original Japanese elements in the eighth century. According to documents and excavational surveys, Kyoto had many gardens once the capital was relocated there during the Heian period (794-1185). In addition, some gardens from the Kamakura period (1185-1333) can still be found in Kyoto City today. It goes without saying that gardens and architecture are inextricably linked. Gardens, like architectural styles and towns, have evolved alongside them. While there have been numerous Japanese gardens established in cities, there have also been those built in Zen temples at the foot of mountains. Nonetheless, all Japanese gardens share a common essence.

Humans have an innate urge to interact with nature and be exposed to greenery. People who are exposed to more greenery are healthier, both physically and psychologically. However, in our globalizing world, green space for outdoor activities is dwindling, as is the amount of time individuals spend in it. Aside from health problems, a global “extinction of experience” has been observed, and studies have shown that those who spend less time in outdoors have less knowledge of or interest in nature. This is especially noticeable among children, who spend less time outside than earlier generations. Soga and colleagues worry that if the current tendency continues, more individuals will become biophobic, threatening future nature and environmental conservation.

Suksheetha Adulla is currently studying Architecture and Urban planning at Newcastle University, United Kingdom. She aspires to become an architectural designer with an intent to fuse her passion towards designing with affection towards environment and build a society in order to inspire, motivate and equip people on a greening journey with sophisticated civilization. She is a caffeine addict who loves playing basketball, reading books, and baking goodies.

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |