How are Gentrification and Displacement Changing our cities?

Background

The post-World War II era set into motion a series of urban developments that paved the way for our modern-day cities and whose effects, both constructive and detrimental, we continue to experience to this day. One of these developments relates to demographic flows in and out of the inner city – rooted in segregation, poverty, and the commodification of housing. This article will unpack the foundational, often enigmatic elements of gentrification and discuss our role, as urban dwellers, in determining the future of our cities.

What is Gentrification?

Gentrification is a phenomenon often understood as the in-migration of upwardly mobile, middle-class households into historically low-income, underprivileged and often racialized neighborhoods. If left on its own, this process can lead to the complete reshaping of neighborhoods, destroying not only the physical architecture but the long-standing social networks and cultural identity specific to the area. Over time, this puts our cities at risk of becoming exclusive, segregated, and homogenous – devoid of the diversity and dynamism our cities are most revered for.

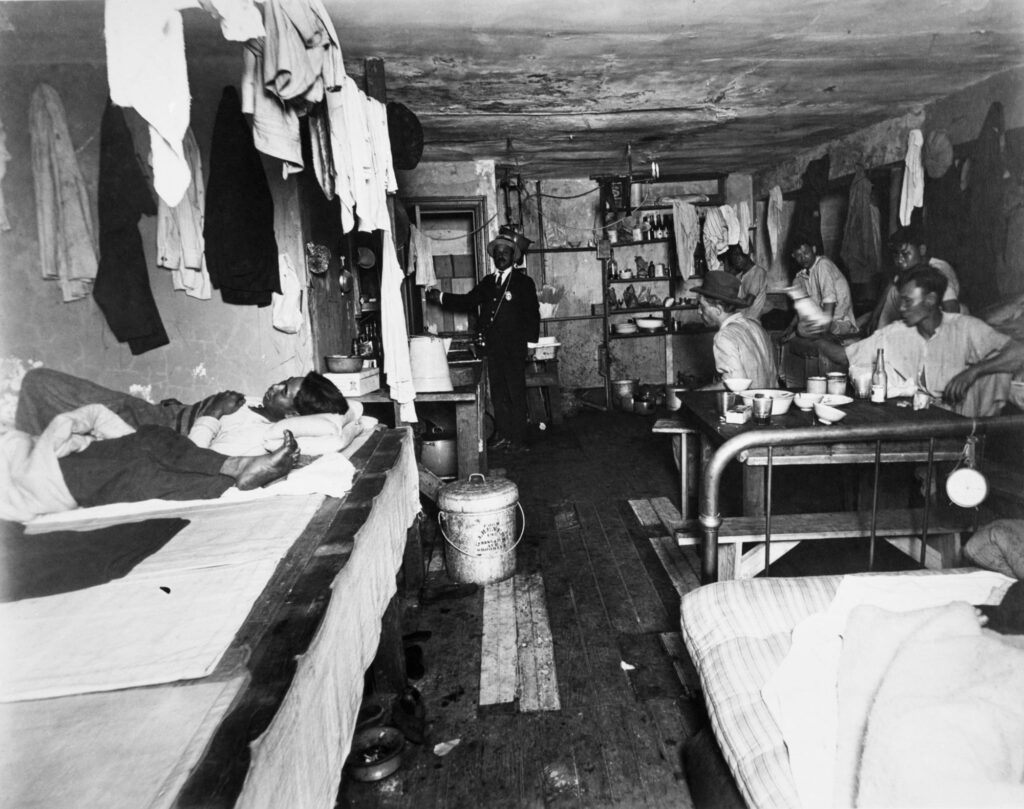

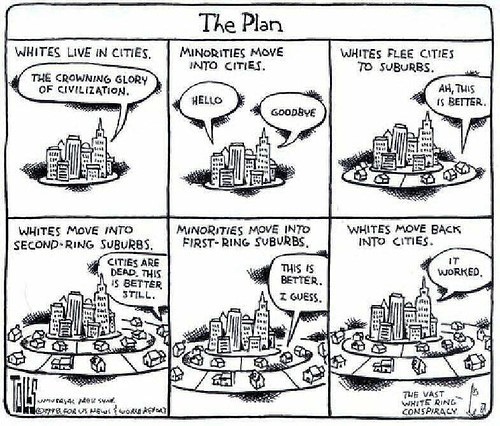

This process was first formalized in the 1950s, with countries mobilizing large scale infrastructure plans to support their post-war futures. With city centers unable to accommodate for the unprecedented population growth, they became plagued with over-crowdedness, sickness, and squalor – creating urban slums. The upwardly mobile households (who predominantly comprised of white, middle-income groups) fled to the suburban fringes, a process famously termed “white flight.” Working-class, racialized groups remained in the inner city in increasingly inhumane conditions.

As a response to these slums, the U.S. government mobilized the urban renewal (or slum clearance) program in the 1950s through the 1970s. The vision of the program was simple – to start from scratch. The government reclaimed and razed large swathes of these “slums” and replaced them with high-rise public housing projects, attracting private investment and funding. While many of these failed (read about it here), these were vital in establishing a precedent for the early model of gentrification – that a neighborhood presenting slum-like symptoms (as determined by decision-makers) could be “revitalized” through private investment, funding, and careful marketing.

Over time, cities would again attract people as centers of commerce, opportunity, and dynamism. But today, cities again are experiencing large scale migration flows. Only now it is working-class, low-income, racialized households that are being pressured towards the fringes. Due to increasing unaffordability, long-standing cultural enclaves are being disrupted by big-box retailers, coffee shops, and high-rise towers. In this structure, white flight and gentrification are parallels of each other. While inversed, the inherent structure remains: mostly white, middle-income households, supported by private investment and government programs, seize high-priority land, while low-income, mostly racialized households are displaced and left underserved.

Key Drivers of Gentrification

Gentrification is an enigmatic process and an outcome of many interrelated factors, including housing demand and price, employment patterns, government regulation and funding, class and racial dynamics, and local city-planning initiatives. While the factors that contribute towards gentrification are locality-specific – and thus must be addressed at the local and regional scales – there exists three key drivers that are universal considerations in framing the issue.

First, gentrification is partially driven by public preference (of the middle-class). There is a strong demand for housing in the inner city because it offers proximity to the economic capital, access to amenities and social infrastructure, and a dynamic, high-density urban experience. Housing demand means increased housing prices which ultimately excludes certain socio-economic groups from residing in these increasingly unaffordable areas. Filion (1991) explains that the process is designed to consolidate the gentrifiers’ class position and builds upon the needs, wants, and preferences of the gentry. It is worth noting that public preference is highly susceptible to marketing schemes, systemic flows, and government urban renewal programs that drive city planning futures in the region.

Second, gentrification is inherently temporal. Aside from the razing of neighborhoods within the U.S. urban renewal program, most instances of gentrification occur over a long period of time. Displacement and cultural loss do not happen overnight but are incremental processes triggered by several phases of government programs, private investment, demographic shifts, or a combination of the three. Hackworth & Smith (2000) highlight waves of gentrification in the U.S. (from the 1960s to the 2000s), where gentrification dwindles and resurges based on societal triggers. These waves, while provoked by independent events or patterns, are vastly interlinked and paint a consistent picture. While the process of gentrification happens over time, its reach is often exhaustive – displacing most if not all of the original occupiers. This temporality can be used as an asset in assessing the urgency of gentrifying neighborhoods and addressing the issue before it worsens. Gentrification continues to evolve and manifest in ways unforeseen.

Third, gentrification often occurs with governmental support, to varying degrees. In contrast to the U.S. urban renewal program, in which the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) took charge, Hackworth & Smith (2000) detail a shift of the state’s role in the modern era, namely as encourager of privatization. This partnership between the state and private investment mobilize gentrification at an unprecedented rate, reclaiming real estate towards more corporate developers and creating a concerted effort towards the financialization of housing stock (Hackworth & Smith, 2000). Brought about by the commodification of housing, the value of housing stock has since shifted from providing homes and sustaining communities to extracting wealth and revenue. Thus, governmental support is integral to mitigating the adverse effects of gentrification on communities.

The Effects of Gentrification

The long-term effects of gentrification are unclear and mired in controversy. Many believe that gentrification poses an overall benefit to the inner city. The National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) (2019) claims that gentrification provides social, economic, and cultural benefits including decreased crime rates, higher employment rates, higher rates of education, greater economic vitality, increased private investment, and an increase in access of neighborhood amenities. But these enhancements only benefit either residents who can remain, avoiding displacement, or the inflow of new residents. The NLIHC, thus classifies displacement, instead of development, as the greatest detriment of gentrification.

The displacement of low-income residents has widespread impacts on the growth and futures of inner cities. A mass exodus of racial, working-class households will bring about a subsequent exodus of culture, tradition, and long-standing networks, sterilizing previously culturally-rich neighborhoods. Over time, these create inner cities that are homogenous and lacking in cultural diversity. In search of more affordable places to live, these displaced households are pressured into the fringes of the city. These can create areas with high concentrations of low-income groups and further reinforces systemic wealth and class inequalities. While those displaced are often racialized households, gentrification can also further racial divides, promoting governmental distrust and social unrest.

The most vulnerable groups include private renters, low-income households, people of color, and people of low levels of education. According to AHURI (2011) and Morris (2017), displaced groups experience a great deal of anxiety and loss at the disruption of their established networks, traditions, and routines. Upon having their lives uprooted, these groups rarely receive the necessary governmental relocation support. Even upon settling in new homes, often far from their original neighborhoods, these feelings of loss persist. Morris (2017, p.158) documents the testimony of a displaced woman upon settling into a new home:

“But then I got here and I just went you know, I just got really depressed when I moved in here. I’m just starting to emerge from it now. I’ve been here 4 months…It’s been awful. I really felt completely traumatized…I think you go through a grieving process once you leave…It’s just really sad.”

It is important to understand that this process of displacement has very real impacts on people and their communities. The human cost of gentrification is dramatic and can sever long-standing social ties and traditions, creating feelings of deep isolation for displaced groups. And this human cost is being experienced all over the world. In an article in The Guardian written in 2016, author Francesca Perry compiles testimonies of groups facing the real effects of gentrification throughout the world (Perry, 2016). From mass evictions in Portugal and displacement in Argentina to loss of culture and diversity in France and the U.S., the impacts of gentrification are unequivocal and powerful.

How can we mitigate gentrification?

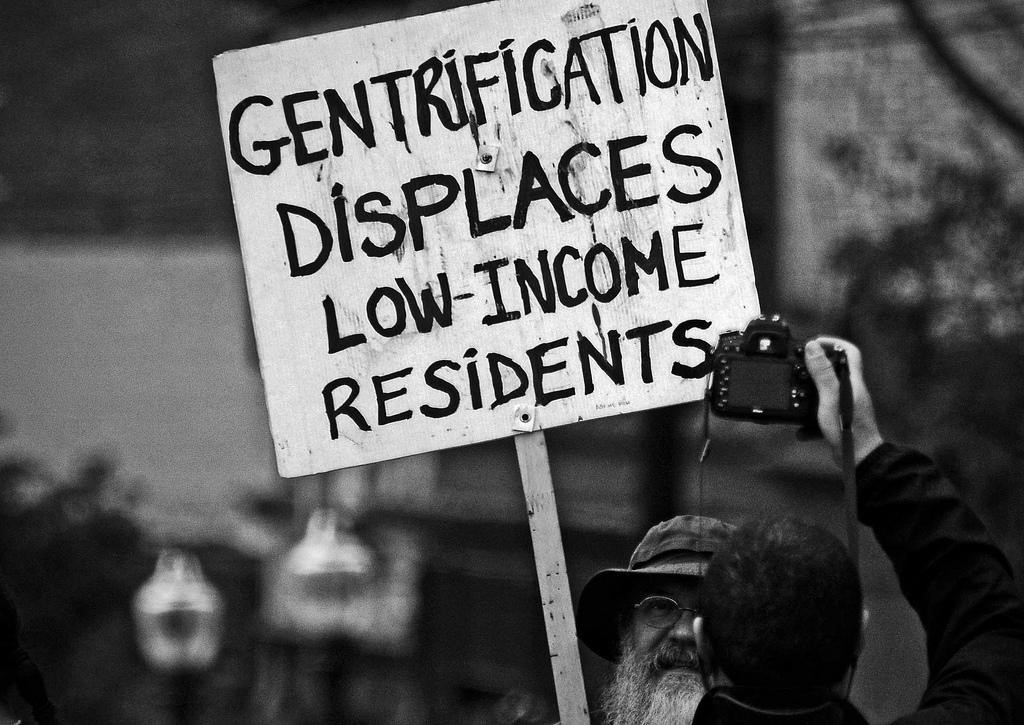

Communities around the world have expressed their concerns and disdain through public actions, including protests, squatting actions, online petitions, and local media blasts. The community opposition calls for the development of governmental programs that both support communities and more heavily regulate private investment. But as governments continue to take a pro-privatization stance, supporting the commodification of housing through deregulatory policy and incentives, Hackworth & Smith (2000) explain that these community efforts are being overwhelmed by institutional forces. At an alarming rate and with little to no oversight, corporate, transnational developers and real estate conglomerates purchase land as financial investments – leading to increased property values and mass displacement.

Governmental support is necessary in mitigating the adverse effects of gentrification. To combat the hyper-commodification of housing through privatization, governments must undergo a paradigm shift – to value the function of housing over its potential economic benefits. Development without displacement must be emphasized. While this shift is idealistic, there are three ways we can help support it.

First, developing an understanding of the issue will empower us to take part in important discourse. Educating ourselves on the impacts of gentrification and displacement in our local communities can create opportunities for us to show support in various ways (e.g. supporting local organizations, attending local info sessions or community workshops, participating in public actions and protests, carrying the conversation into our spheres of influence, etc.) This contributes to informed, robust community networks that can hold political sway. Second, to bolster these networks to pressure political decision-makers in recognizing and addressing the local realities of gentrification. While “make your vote count” can often lead to equally disappointing outcomes, it is important to elect government officials that are more likely to protect communities over the pockets of private investors. Find opportunities at public consultation events or workshops to make your voice heard.

Third, hard, statistical data and precedent analysis are effective ways in quantifying the effects of gentrification. This data, in the form of published works, peer-reviewed studies, and mapping analyses, can provide an empirical basis to gentrification that governments cannot ignore. These are vital in shedding light on the urgency of the issue and strong-arming governments into action.

As architects and urban designers, we have a responsibility to protect the vitality of our cities. This goes beyond the design of beautiful spaces but relates to preserving the cultural heart of our cities – and ensuring they are safe, inclusive, and equitable places to live.

References

This article provides a brief entry point to the enigmatic issue of gentrification and displacement. Below are few additional resources to delve into the subject:

- Francesca Perry. (2016). ‘We are building our way to hell’: tales of gentrification around the world.

- NLIHC. (2019). Gentrification and Neighborhood Revitalization: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

https://nlihc.org/resource/gentrification-and-neighborhood-revitalization-whats-difference

- Jason Hackworth & Neil Smith. (2000). The Changing State of Gentrification.

- Alan Morris. (2017). “It was like leaving your family”: Gentrification and the impacts of displacement on public housing tenants in inner-Sydney.

- AHURI. (2011). Gentrification and displacement: the household impacts of neighborhood change.

- Mapping analysis studies – https://www.urbandisplacement.org/

About the Author

Ivanne Cheng is currently a student at the University of Sydney pursuing a Masters in Urbanism specializing in Urban Design. He wants to help shape cities towards becoming more thoughtfully designed, environmentally sustainable, and reflective of the needs of their inhabitants. He enjoys hiking, playing Smash Bros., Jiu-Jitsu, and giving his two dachshund dogs the attention they deserve.

Conclusion

References

About the author

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

Gis Made Easy- Learn to Map, Analyse and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

15th-19th December 2025

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “