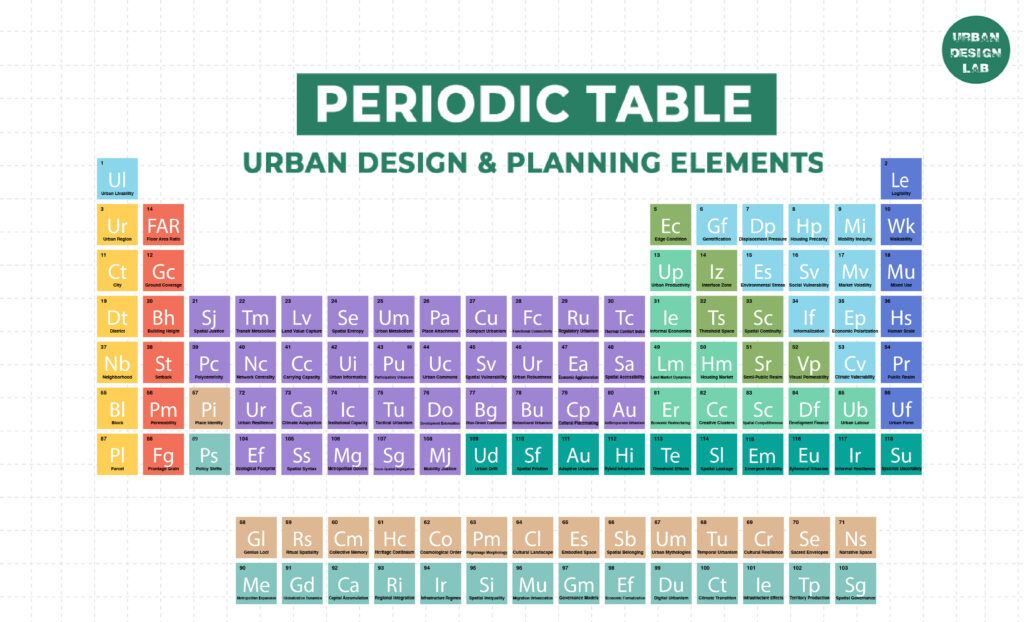

Periodic Table for Urban Design responds to a century of fragmented urban scholarship by offering a single, coherent framework for understanding cities as interconnected systems rather than isolated problems. Urban design, planning, economics, sociology, geography, engineering, and political science have long operated in silos, each describing only a piece of the urban puzzle. Yet cities function as multiscalar, relational ecologies in which form, culture, infrastructure, governance, and markets continually shape one another. This periodic table closes that gap by organizing key urban concepts into clear families—foundational, transitional, reactive, transformative, revealing their structural affinities and systemic interactions. More than a taxonomy, it becomes a cognitive scaffold: a concise, intuitive way to grasp the full complexity and interdependence of urban life.

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

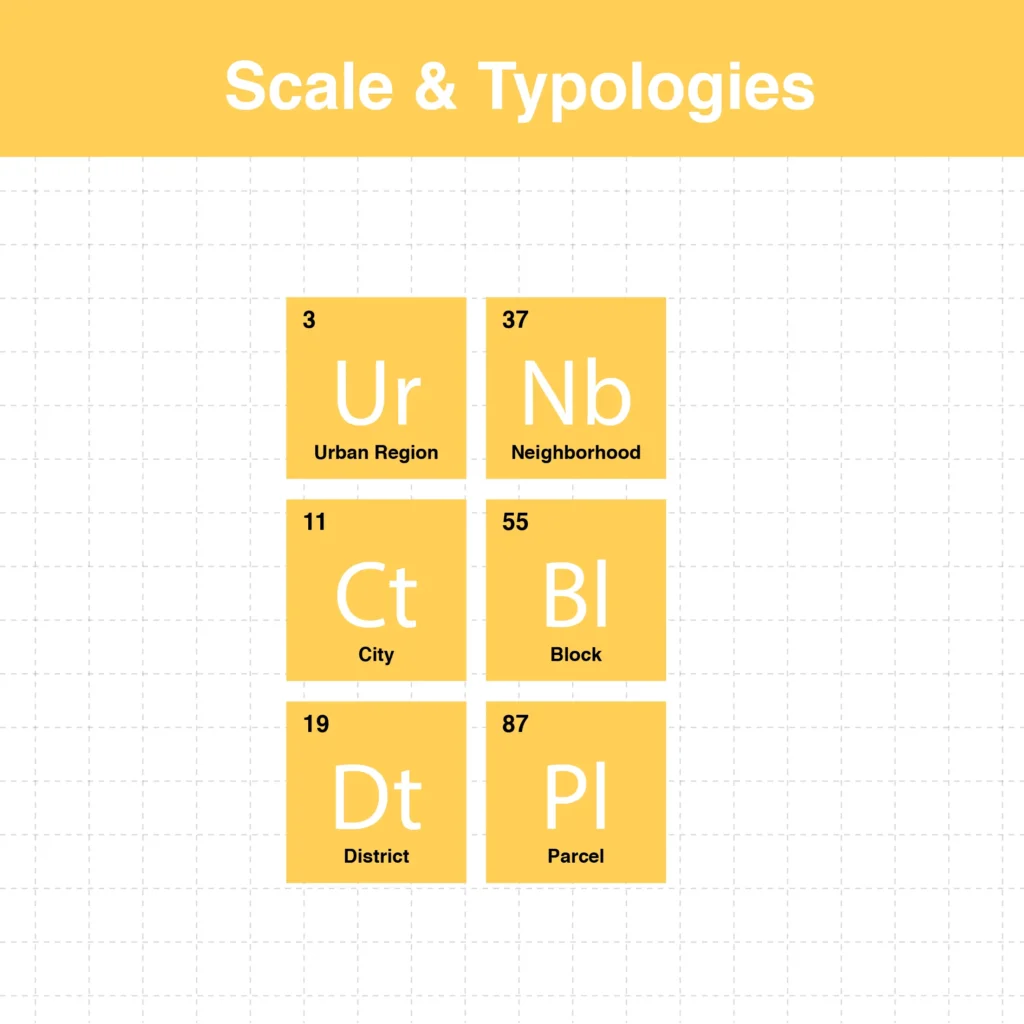

1. Scale & Typologies

If urbanism possesses a grammar, then scale constitutes its deep syntax, the structuring logic through which cities articulate form, function, and lived experience. The movement from region to parcel is not merely a shift in physical magnitude; it is a shift in epistemic register, revealing how governance structures, infrastructural systems, market behaviors, and social worlds are nested within one another. This group sits at the base of the Urban Periodic Table because it describes the fundamental geometries and scalar thresholds through which all urban processes materialize. At the metropolitan end, the Urban Region (UR) orchestrates polycentric labor markets and mobility networks, functioning as the true economic and spatial engine of contemporary urbanization. The City (CT) operates as the institutional anchor of planning authority, service delivery, and political identity. The District (DI) mediates land-use structure and infrastructural distribution at an intermediate scale, while the Neighborhood (NB) crystallizes social cohesion, everyday mobility, and walkable urbanism. At the micro-scale, the Block (BL) determines permeability, grain, and urban morphology, and the Parcel (PR)—the atomic unit of urban development—becomes the site where regulation collides with architectural intent and economic feasibility.

Taken together, these six elements build the hierarchical scaffolding that conditions every subsequent dimension of urban life. Density, transit access, ecological performance, affordability, and public space quality, all are contingent upon how these scalar units are configured and governed. Understanding this taxonomy of scales is therefore not a descriptive exercise but a disciplinary imperative: it allows us to interpret cities not as amorphous territories, but as layered spatial ecologies in which decisions at one level reverberate across all others. For the urban designer, this group is the epistemic starting point—the foundation upon which analytical clarity, design coherence, and systemic insight are constructed.

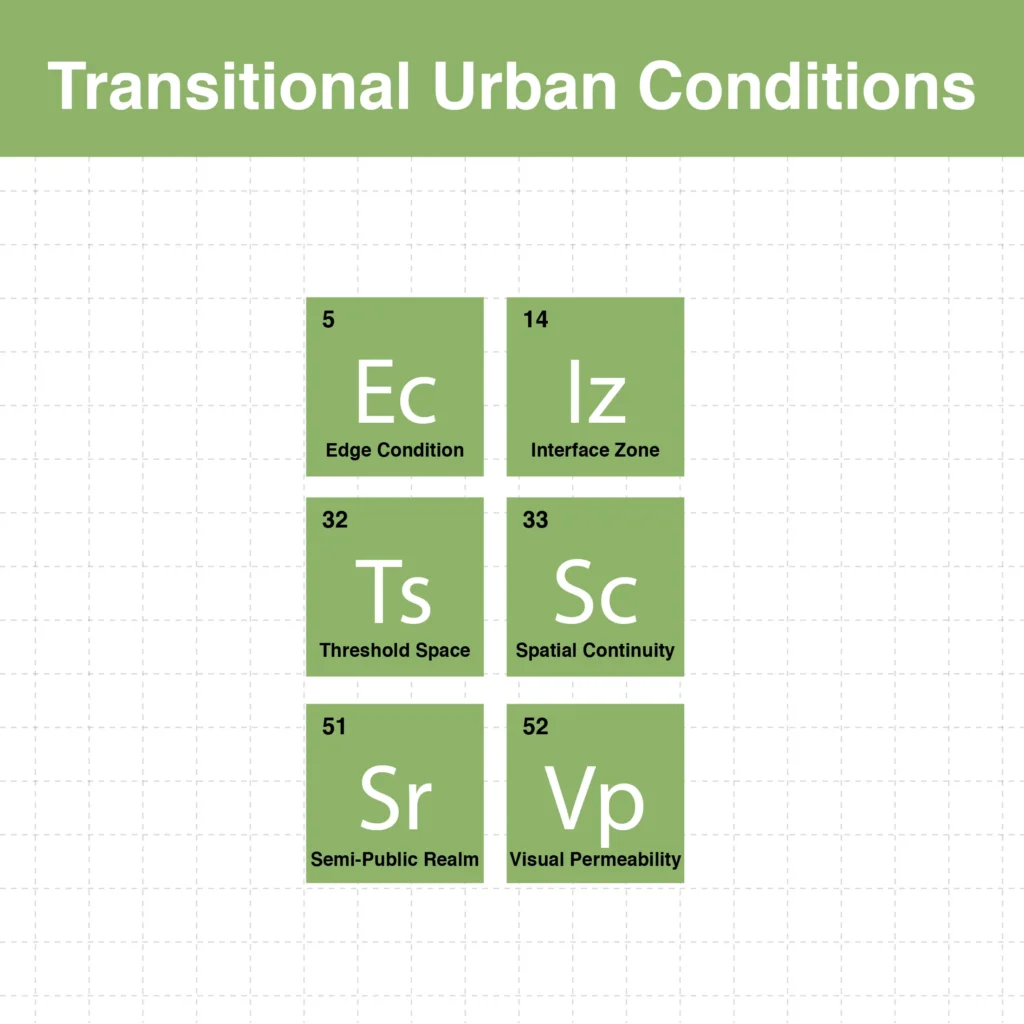

2. Transitional Urban Conditions

Transitional Urban Conditions represent the most sensitive and behaviour-shaping layer of the built environment, the micro-territories where public, semi-public, and private domains overlap, negotiate, and continuously redefine one another. Unlike large-scale morphologies or infrastructural systems, these are liminal geometries: the edge of a plinth, the permeability of a frontage, the depth of a threshold, the continuity of a façade line. They are the spatial instruments through which cities choreograph human behaviour—regulating encounter, social trust, safety, territoriality, and the psychological perception of openness or enclosure. Scholars from Gehl and Whyte to Madanipour and Hillier have demonstrated that these in-between zones are not marginal; they are generative. They determine how streets breathe, how communities interact, and how form acquires meaning in everyday use.

Edge Condition (Ec), Interface Zone (Iz), Threshold Space (Ts), Spatial Continuity (Sc), Semi-Public Realm (Sr), and Visual Permeability (Vp) together form a taxonomy of urban negotiation. They act as spatial membranes that calibrate sightlines, mediate access, and encode cultural expectations about privacy, hospitality, and publicness. A well-designed edge invites participation; a fractured interface produces social fragmentation. A continuous spatial rhythm strengthens urban legibility; a broken one erodes collective coherence. These elements are the scalar micro-physics of the street, where the city translates its form into human experience. In this group, urbanism becomes less about geometry and more about relational energy, how space governs behaviour, and how behaviour, in turn, reorganizes space.

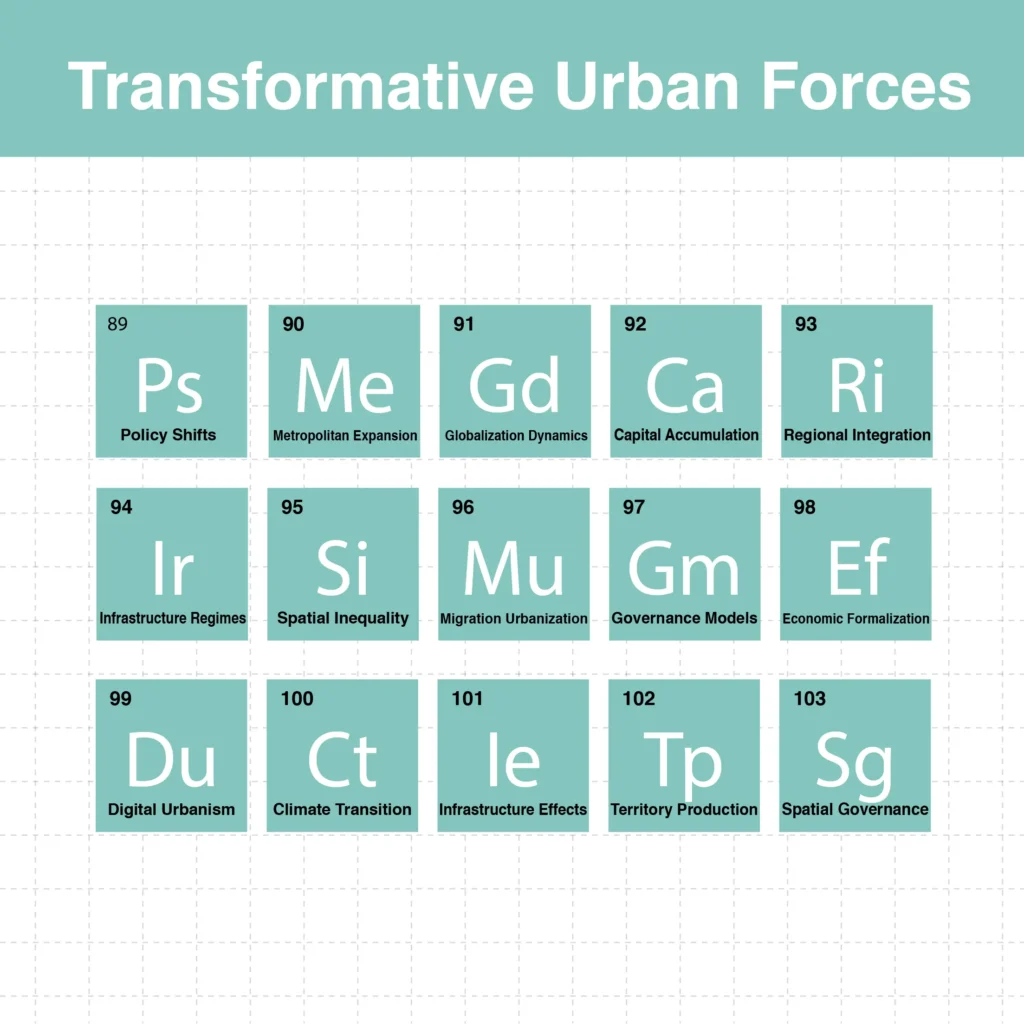

3. Transformative Urban Forces

Transformative Urban Forces represent the macro-scale drivers that fundamentally redirect the evolution of cities, often in ways that exceed the control of local planning. These are not incremental design adjustment, they are structural realignments that reconfigure entire metropolitan systems, territorial logics, and socio-economic landscapes. Metropolitan Expansion (Me), Globalization Dynamics (Gd), and Capital Accumulation (Ca) describe how economic flows, investment cycles, and geopolitical forces organize urban growth far beyond the scale of neighborhood or district. Regional Integration (Ri) and Spatial Governance (Sg) act as institutional architectures that bind cities into megaregions, while Infrastructure Regimes (Ir) and Infrastructure Effects (Ie) create long-term path dependencies: once infrastructure is laid down, it “locks in” spatial futures for decades.

These forces do not operate neutrally, they produce winners and losers. Spatial Inequality (Si), Migration Urbanization (Mu), and Economic Formalization (Ef) capture the socio-spatial restructuring that accompanies growth, often manifesting as uneven development, labor stratification, and contested territorial claims. Policy Shifts (Ps), Governance Models (Gm), and Digital Urbanism (Du) reshape how cities are managed, surveilled, financed, and planned in an era of data-driven decision-making. And Climate Transition (Ct), perhaps the most consequential of all, forces cities into an unprecedented recalibration of energy systems, ecological baselines, and risk geographies. Together, these 15 elements illustrate that contemporary urbanization is governed not by static master plans but by planetary-scale forces, fluid, powerful, and deeply entwined with capitalism, technology, and climate. Planners who ignore these forces design for the city they wish they had; planners who understand them design for the city that is inevitably emerging.

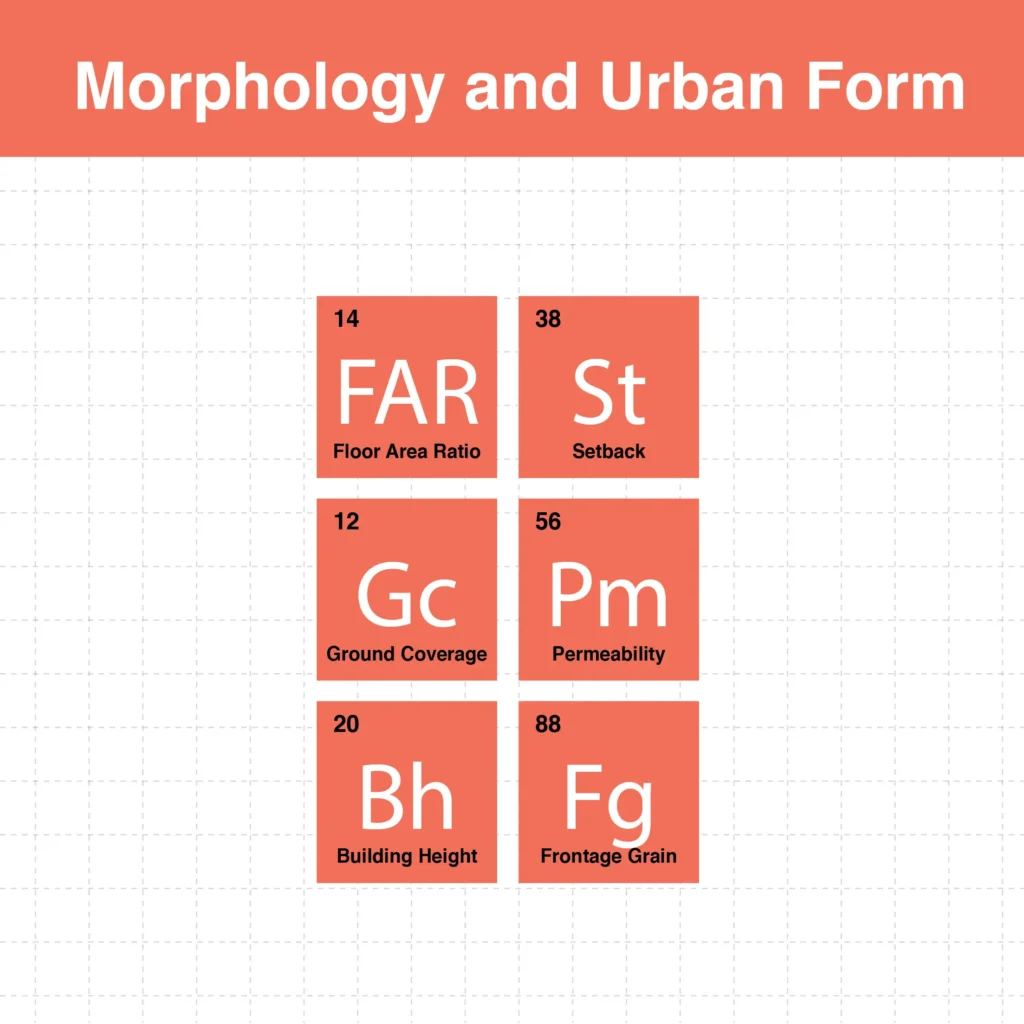

4. Morphology and Urban Form

Morphology and Urban Form concerns the deep structural and cultural logics that give cities their intelligibility, identity, and experiential richness, a far more profound reading of form than mere geometry or building massing. This group brings together the elements that shape how urban environments acquire meaning over time: Place Identity (Pi), Genius Loci (Gl), Ritual Spatiality (Rs), and Collective Memory (Cm) define how people emotionally and symbolically locate themselves within the city. Heritage Continuum (Hc), Cultural Landscape (Cl), and Sacred Envelopes (Se) reveal how cultural, spiritual, and ecological layers sediment into form, producing landscapes that are simultaneously material and metaphysical. Cosmological Order (Co) and Pilgrimage Morphology (Pm) speak to ancient urban grammars—alignments, processional routes, and cosmic orientations—that have structured cities for millennia. Meanwhile, Embodied Space (Es), Spatial Belonging (Sb), Narrative Space (Ns), and Urban Mythologies (Um) foreground the lived, phenomenological, and narrative dimensions of urban form. Together, these elements position morphology not as static physicality but as a cultural-phenomenological field in which memory, ritual, cosmology, and meaning continuously shape and reshape the built environment.

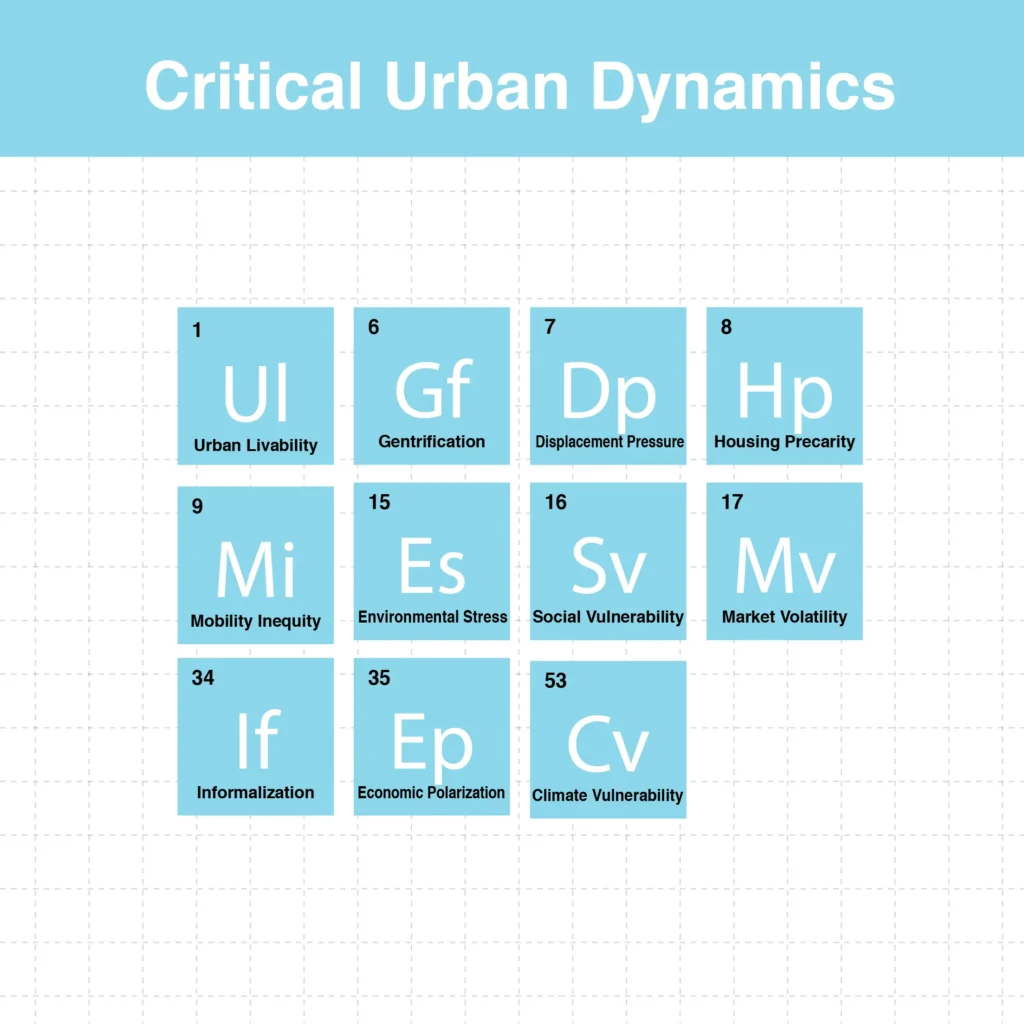

5. Critical Urban Dynamics

Critical Urban Dynamics encompass the high-pressure socio-environmental stresses that destabilize or accelerate urban change, often faster than institutions or physical systems can respond. These forces: Gentrification (Gf), Displacement Pressure (Dp), Housing Precarity (Hp), and Informalization (If)—reveal how economic and regulatory constraints reshape access, tenure, and belonging, producing uneven geographies of security and insecurity. At the same time, Mobility Inequity (Mi), Environmental Stress (Es), Social Vulnerability (Sv), and Climate Vulnerability (Cv) expose how infrastructure gaps, demographic risk, and ecological hazards disproportionately impact marginalized populations. Together, these elements expose the fault lines of the urban condition: the places where structural inequality, climate risk, and economic turbulence intersect.

What makes these dynamics “critical” is not only their severity but their reactivity—they trigger cascading effects across governance, land markets, public health, and ecological systems. Market Volatility (Mv) and Economic Polarization (Ep) amplify these cycles, generating boom-and-bust development patterns and spatial concentrations of privilege and deprivation. Urban Livability (Ul), placed at the center of this cluster, becomes both a diagnostic and an aspiration, capturing the cumulative impact of these pressures on daily life. In this group, the city reveals its most vulnerable, contested, and rapidly shifting terrains.

6. Emergent Urban Phenomena

Emergent Urban Phenomena represent the volatile, adaptive, and often unpredictable behaviours that surface when cities operate under conditions of complexity, technological disruption, and socio-environmental stress. These elements—Urban Drift (Ud), Spatial Friction (Sf), Adaptive Urbanism (Au), Hybrid Infrastructures (Hi), Threshold Effects (Te), Spatial Leakage (Sl), Emergent Mobility (Em), Ephemeral Urbanism (Eu), Informal Resilience (Ir), and Systemic Uncertainty (Su)—capture the ways in which urban systems subtly reorganize themselves beyond formal planning logics. They reveal a city that constantly experiments: shifting desire lines, improvised infrastructures, pop-up economies, mobility innovations, and reactive adaptations to climate shocks or governance gaps. In this group, the city behaves less like a planned artifact and more like a dynamic organism—one that evolves in real time, producing spatial patterns and social behaviours that challenge prediction and demand new forms of agile, anticipatory planning.

7. Urban Systems & Frameworks

Urban Systems & Frameworks constitute the deep operational architecture of the city—the interconnected infrastructural, regulatory, ecological, and mobility systems that make urban life possible and shape its long-term trajectories. This group brings together structural principles like Spatial Justice (Sj), Network Centrality (Nc), Carrying Capacity (Cc), and Urban Metabolism (Um), alongside governance and institutional mechanisms such as Regulatory Urbanism (Ru), Institutional Capacity (Ic), and Socio-Spatial Segregation (Sg). At the same time, elements like Transit Metabolism (Tm), Functional Connectivity (Fc), Mobility Justice (Mj), and Spatial Accessibility (Sa) reveal how movement systems organize opportunity, time, and social equity. Environmental frameworks—from Blue-Green Continuum (Bg) and Ecological Footprint (Ef) to Climate Adaptation (Ca) and Urban Robustness (Ur), highlight the metabolic and resilience logics upon which urban sustainability depends. Together, these elements form the systemic backbone of contemporary urbanism, demonstrating that cities do not simply exist as built form—they operate as complex, adaptive infrastructures whose performance emerges from the alignment (or misalignment) of policy, energy, ecology, technology, and social frameworks.

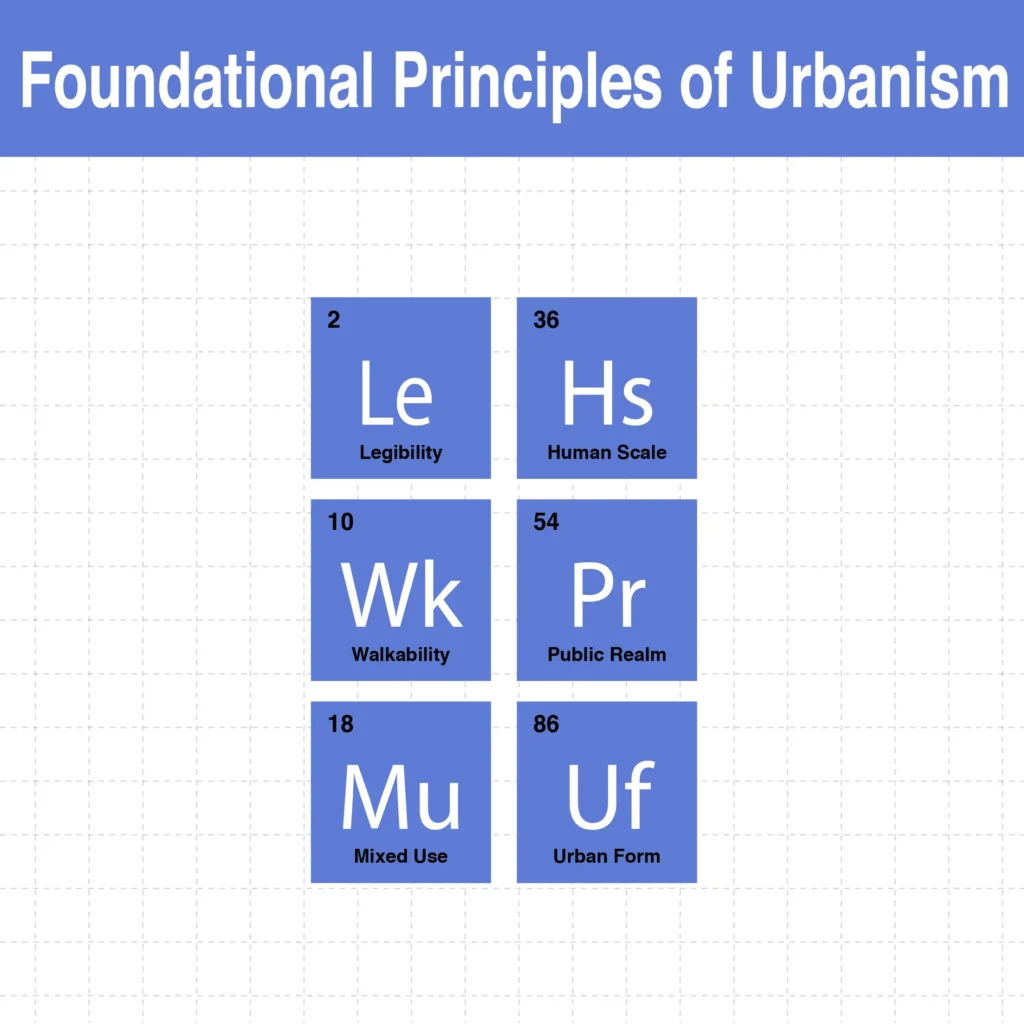

8. Foundational Principles of Urbanism

Foundational Principles of Urbanism articulate the timeless, cross-cultural doctrines that anchor human-centered city-making, forming the conceptual core from which all contemporary urban design practice has evolved. These principles: Legibility (Le), Human Scale (Hs), Walkability (Wk), Public Realm (Pr), Mixed Use (Mu), and Urban Form (Uf), represent the enduring insights of thinkers such as Kevin Lynch, Jane Jacobs, Jan Gehl, Christopher Alexander, and Allan Jacobs. Together they affirm that cities succeed not through monumental gestures or technological spectacle, but through clarity, accessibility, intimacy, and diversity. Legibility enables people to understand and navigate the city with confidence; Human Scale ensures that built form aligns with the physical, perceptual, and social capacities of the human body; and Walkability organizes urban life around proximity, encounter, and movement rather than automotive dominance. The Public Realm stands as the democratic stage of civic identity, while Mixed Use generates vitality, safety, and economic resilience through diversity of functions. Underpinning all is Urban Form, the structural grammar of blocks, streets, and edges that shape how the city is experienced and inhabited. These principles form the moral and spatial compass of urbanism: the essential criteria by which we evaluate whether a city truly serves the people who live in it.

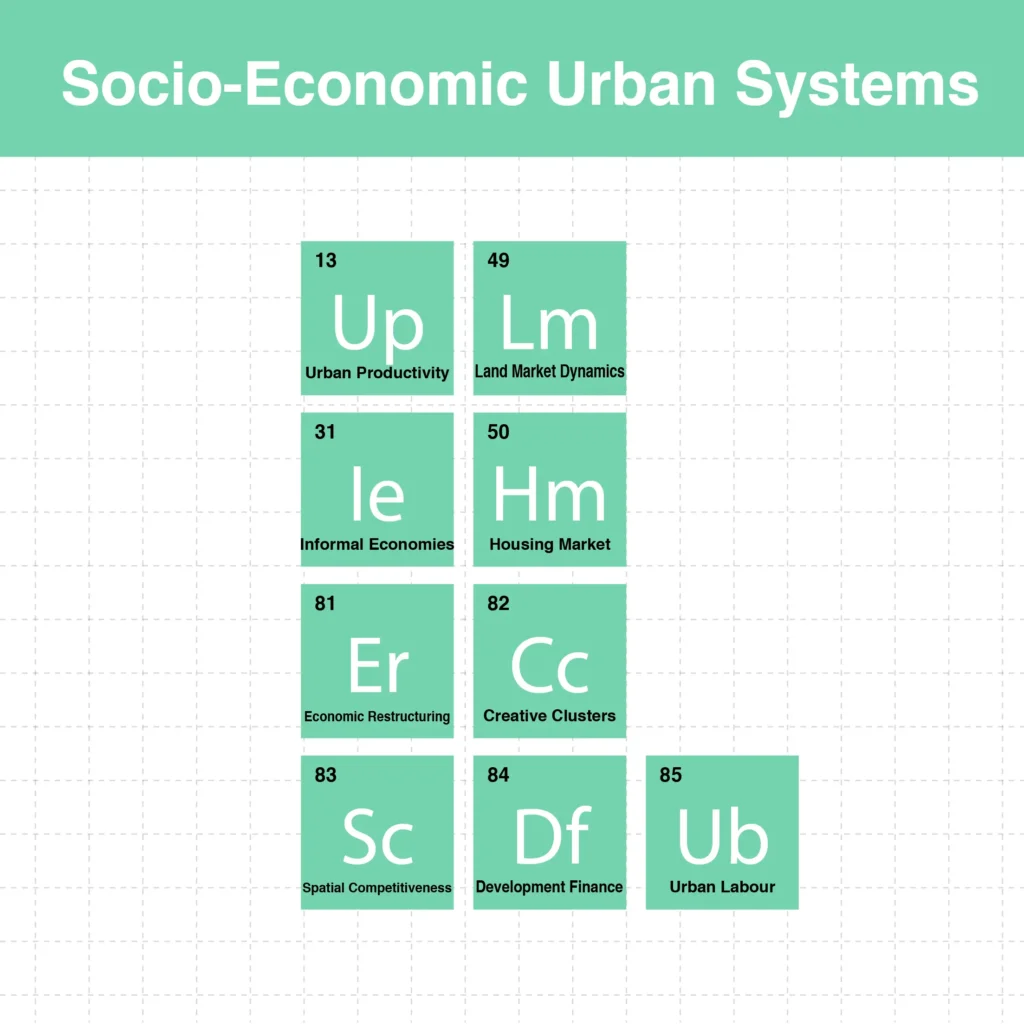

9. Socio-Economic Urban Systems

Socio-Economic Urban Systems capture the economic engines, labour dynamics, and market behaviours that underpin how cities function, grow, and distribute opportunity. These systems: Urban Productivity (Up), Land Market Dynamics (Lm), Informal Economies (Ie), and the Housing Market (Hm), form the structural core of urban livelihoods, determining how value is created, captured, and contested across space. Economic Restructuring (Er) and Creative Clusters (Cc) highlight how global shifts, technological change, and cultural industries reshape urban competitiveness and sectoral composition. Meanwhile, Spatial Competitiveness (Sc), Development Finance (Df), and Urban Labour (Ub) illuminate the mechanisms through which cities attract investment, mobilize capital, and organize their workforces.

10. Cultural–Spatial Foundations

Cultural–Spatial Foundations articulate the deepest stratum of urban meaning, the symbolic, ritualistic, and memory-laden structures through which places become more than geometry and infrastructure. This group brings together elements such as Place Identity (Pi), Genius Loci (Gl), Ritual Spatiality (Rs), and Collective Memory (Cm), which capture how people co-produce the emotional, spiritual, and symbolic resonance of urban environments across generations. Concepts like Heritage Continuum (Hc), Cultural Landscape (Cl), and Sacred Envelopes (Se) reveal how cultural practices, ecological rhythms, and spiritual cosmologies sediment into the built form, shaping not only architecture but entire urban morphologies. Meanwhile, Cosmological Order (Co), Pilgrimage Morphology (Pm), Embodied Space (Es), and Spatial Belonging (Sb) highlight the ways in which bodily movement, ritual performance, and cultural orientation systems structure lived spatial experience. Completing this constellation, Urban Mythologies (Um), Temporal Urbanism (Tu), Cultural Resilience (Cr), and Narrative Space (Ns) underscore how stories, rhythms, and collective memory continue to animate cities long after plans, regimes, or even buildings disappear. Together, these elements remind us that cities are not merely engineered—they are cultural organisms, repositories of meaning, and lived archives of human continuity.

Urban Design Lab

About the Author

This is the admin account of Urban Design Lab. This account publishes articles written by team members, contributions from guest writers, and other occasional submissions. Please feel free to contact us if you have any questions or comments.

Related articles

Remembering Frank O. Gehry: The Architect Who Redrew Skylines

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

History of Urban Planning in India

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

Top Urban Destinations for Architecture Tours Beyond the Usual Stops

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

6 Comments

For me, urban design in this way was amazing and new. Please send me the complete periodic table of urban design.

Thanks

You clearly know your stuff. Great job on this article.

What an engaging read! You kept me hooked from start to finish.

I enjoyed your perspective on this topic. Looking forward to more content.

I love how well-organized and detailed this post is.

Love the visual.