Crowd-sourcing the Public Participation | Planning Projects

Public Participation and Crowd-sourcing

Public participation is a major concern for urban planners. Planners are facing a challenge on how to implement strategies, involving the public in decision making processes. This article defines a crowd-sourcing model as a successful web-based, problem-solving tool for business, arguing that crowd-sourcing is an important tool to enable community participation in planning projects. This article begins by exploring some of the public participation challenges in urban planning projects while in the decision making processes. Later the article explains the theories of collective intelligence and crowd wisdom by highlighting that the web as a medium is an important technological tool to tackle areas earlier used to be far-reaching.

The Challenge

We live in a world where planners are responsible for the implementation of various strategies, approaches, and policies with regard to the world’s challenges. Brabham (2006) argued that involving the community in planning projects seems to be the best option for problem solving in democratic societies. The urban disciplines together with urban planning have adopted participation and collaboration in participatory democracy. However, urban planners are failing to enlarge the participation process and give them an opportunity to share their opinion in designing solutions for urban problems. In practice, there are challenges of encouraging public participation and drawing creative solutions in public planning meetings (Campbell & Marshall, 2000).

There is a need to consider technological tools such as Web-based which enables to tackle collective intellect among the population in a way that it would be impossible in face to face meeting. The Web has proven itself as a collaborative tool for the design of real spaces and planning the built environment. I therefore argue that the crowd-sourcing model is an appropriate tool for enabling the citizen participation process in public planning projects. My arguments will be broken down as follows: exploration of the public participating challenges in urban planning projects when it comes to decision making processes. Followed by the theories of collective intelligence and crowd wisdom, and lastly will be recommending crowd-sourcing models to be applied in practice to facilitate the public participation process.

Public participation, creative solutions and democracy

A debate body of planning literature has admitted the positive impacts of public participation in planning projects. Public participation can be seen as a logical extension of the democratic process in various ways (Pimbert & Wakeford, 2001). Giving citizens an opportunity to share their opinions in decision making processes ensures sustainable development (Burby, 2003). Between 1970 and 1980 Crewe (2001) discovered in his analysis of community participation in the Boston Southwest Corridor project that the more designers value citizens’ views and opinions, the more their designs will be. Fiskaa (2005) added by saying that the main aim of involving the public in matters that affect them is to obtain better plans.

Non-expert knowledge

The other positive impacts of public participation is the valuing of non-expert knowledge brought into the decision making process of planning projects. Participation is defined as the act sharing views and opinions in the decision making process (Hanna, 2000). Van Herzele (2004) found that including non-expert opinions and knowledge has a positive impact on the planning process, since the perspectives of individuals outside the urban planning profession can bring about creative solutions to the problems faced by the local community.

Furthermore, Lakhani & Jeppesen, 2007; Lakhani & Panetta, 2007; Lakhani et al 2007) have found great success in planning projects where the citizens were given an opportunity to participate, with solutions that are superior and more cost-effective than traditional research and development programs. Corburn (2003) argues that planners should never ignore local knowledge that seeks to improve the quality of lives of communities, particularly the poverty-stricken ones.

It is immodest to think that only professional planners can formulate planning solutions, and perhaps more so to think that experts can identify precisely which and how many non-experts would be of value to the project. Citizens’ knowledge adds the perspective of the future user of a designed space and the insights about the environment and place that the planning discipline might never have thought of (Burby, 2003).

Cautioning against public participation

A body of literature has emerged with challenges of involving the public in planning projects based on specific cases and long-range studies. Abram & Cowell (2004) argued that success in public participation may be culture specific. Different cultures have different levels of transparency with regards to public participation in government processes (Alfasi, 2003). Nace & Ortolano (2007) argue that success in public participation may be project specific, noting that public participation in a Brazilian urban sanitation plan had mixed results relating to performance of the plan.

Brody (2003) argues that there is no solid absence with regards to success in public participation. He added that involving citizens in planning projects may result in conflicts and debates at the negotiating table, which will then slow down the decision making process.to be specific, the manner in which planners conduct meetings have both the positive and negative impacts on material outcomes (Carp, 2004). The presence of special interest groups in the decision making process who show up to planning meetings representing the interests of some facet of the public, may intimidate the average citizen with elaborate charts, maps, and solid evidence, thus discouraging future involvement by the community members (Hibbard & Lurie, 2000).

The recent studies by Hou & Kinoshita (2007) and Innes et al. (2007) found that the lack of formality during the public participation process had an impact on the public’s contribution to the development of the plan as they viewed themselves as important stakeholders in decision making processes. Forester (2006) argues that it is easy to preach, but difficult to apply it in practice. Effective public participation in planning requires transparency and sensitivity. In the past years traditional public participation methods have played an important role, so it should not be underestimated.

Network democracy

The purpose of this article is to bring into action a practical, technology driven alternative to the traditional public participation process. With regards to involving the public in urban planning, either by law or voluntarily, in theory and in practice, the discipline of planning has embraced the notion of a more deliberative form of democracy. In deliberative democracy, equality, identity between governing and governed, and popular sovereignty are the key principles of government and all competing parties are all seen as in productive conflict with each other (Mouffe, 2000).

Collective intelligence and the Web

If the reason behind valuing citizen’s knowledge is the fact that they may bring new ideas that planners would have never thought of, then the question is how best to maximize the citizen’s contribution. The expectations of scaling up the public participation process and the efforts to engage non-experts into the planning projects would do the trick.However, such actions are costly and labor-intensive. On the Web, though the undefined, non-expert talet is out there accessible through the seemingly infinite scaled-up platform of the internet.

Collective intelligence

According to Levy (1995) collective intelligence is defined as a form of universally distributed intelligence, which is constantly enhanced, coordinated in real time, and resulting in the effective mobilization of skills. His logical choice to tackle this was through the Web. using collective intelligence and networks for problem solving can be scaled to address global concerns (Ignatius, 2001). There are currently various modes of technology (internet-based) which encourage global communication and problem solving (Masum & Tovey, 2006).

The medium of the web

The importance of the Web is that it enables a type of networked, creative thinking, encouraging the mind to wander down winding paths to unknown mental explorations. In addition, the Web enables the precise form of aggregation Surowiecki stipulates for a successful crowd. As it is mentioned earlier that collaboration and communication between stakeholders may lead to conflicts, an alternative is to allow individuals to give their perspective and put them for a review among their peers in the crowd. The crowd can then examine the bad ideas to find the good ones, and this can be done through a simple online voting scale.

Another aspect that makes the web an ideal medium for facilitating creative participation includes its speed, reach, asynchrony, anonymity, interactivity, and its ability to carry every other form of mediated content. Through the Web, messages and the exchange of ideas travel so fast along its channels that the medium works in effect to reduce the issue of time. Furthemore, the Web has more or less global reach, which simply means that communication can take place between people in different places.

The Web is asynchronous mode, that is the online bulley=tin board systems and similar which enables users to share their ideas to virtual location at one point in time, and other users can engage those thoughts at much later points in time. The Web can foster a sense of an ongoing dialogue between members of the community without those members having to be present at the same time (Ostwald, 1997). Some of the urban planning projects have already considered the Web. This is done by posting podcasts and meeting minutes on panning project Web sites.

Planning decisions are not only about the will of the simple majority. They are about the ways in which communities are given an opportunity to share their perspective on matters that affect them and their needs and expectations to ensure sustainable development. The Web is an anonymous medium, which allows users to develop their own online identities in their own terms, or choose to remain anonymous. People are free to share their ideas in a platform where they are anonymous without the fear of non-verbal politics.

The Web is a technological tool and site of convergence where all other forms of media can be utilized. It would seem that public participation programs folded into urban planning processes try to achieve this meeting in the middle of ideas. It can therefore be concluded that Web users are potentially problem solvers, and bring about creative solutions. There is a need to shift to the Web to transform the public participation process in planning projects, and to enlarge our narrow perspective on how citizens actually participate in democracy today (Mack, 2004).

What is crowd-sourcing ?

Crowdsourcing is defined as a mechanism for leveraging the collective intelligence of online users towards productive ends. Jeff Howe (2006) created the word crowdsourcing in an issue of Wired magazine. The term describes a new-based business model that tackles the creative solutions of a distributed network of individuals through what amounts to an open call for proposals (Brabham, 2008). He added saying that it is only crowdsourcing once a company takesthat design, fabricates it in mass quantity and sells it, which simply means that a company will post a problem on their online web. People participate by sharing their ideas, and the winning ideas are awarded a reward. The company then uses those ideas for its own gain (Brabham, 2008). Brabham (2008) and Howe (2008) outlines some of the notable cases of crowdsourcing, all of which are for profit business cases. In a community, users can do things such as designing, voting, shopping, and chatting in the user forum.

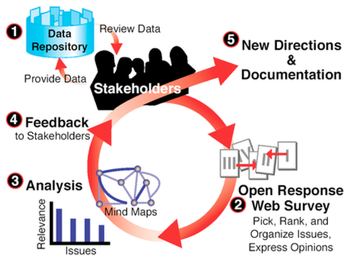

How to crowdsource public participation in planning projects?

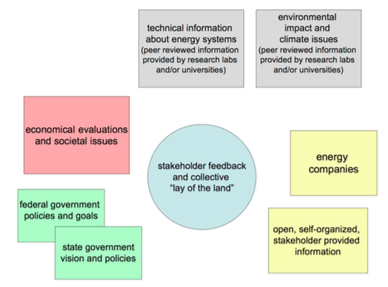

To argue the necessity of crowdsourcing models for public participation in planning projects, I will illustrate the model in a hypothetical planning case. In order to begin crowdsourcing the public participation process, the city would have to first analyze its problem, such as what is the time table? How many more residents might it bring to the city?. Such questions would form the basic elements of crowdsourcing. In addition, having a detailed scope of the proposed project, the city would have to take into account the available data, and resources available for development as part of coordinating the work of all three spheres of government in a coherent manner to improve the quality of life of people living in that region.

This would mean any and all maps, and location of parks will be used as evidence for the call. In addition, technical data such as dimensions of roadways, environmental and municipal laws and codes, traffic flows data, the crowd’s ability to handle complex data should be taken into consideration (Schlosberg & Shuford, 2005). The call for solution, together with the available data will be posted on the city’s online Web site. The winning solutions will be rewarded by the city in the form of cash and free utilities for a few years. For Example, if the city wants to know where the community wants various parks, or how they desire the shapes of streets, a template will be offered. The template will consist of shapes designating various buildings and spaces. Users will then be able to move the shapes around within a geographical boundary proposed for the project.

The city’s residents proposal would be available online in the form of a gallery, where citizens are able to contain an online bulletin board and vote on the best designs. At the end, it will be the city’s willingness whether to implement the winning solutions in the crowdsourcing contest, and use the top vote-getting designs and use them as an advisory tool in the design of the actual plan through traditional public participation methods. In addition, the city could choose to combine data from two or more top plans for an overall creative solution.

In the end, the city’s hypothetical crowdsourcing experiment will achieve a lot, such that citizens would be given authority to participate. Any citizen granted access to internet-connected computers, would have access to the online participation process. This process does not only accommodate those excluded from the participation altogether, but also accommodate those who are typically involved, but drowned out by polar arguments and the influence of experts. Furthermore, citizens would have an opportunity to participate in a manner that meets their needs and expectations (Maier, 2001).

Another benefit of crowdsourcing the public participation process is that it gives rise to new and creative ideas that a panel of planners would have never thought of, or would have suggested otherwise. Local knowledge carried out from the daily experience of citizens adds insights into the decision making process. Some of these local proposals might be su[erios solutions because the ideas might consider the unique needs of diverse constituencies (Brabham, 2007).

Challenges for crowdsourcing

The challenges of crowdsourcing models is an obvious limitation in the digital divide, between those who have access to computers, computer skills, and internet access and those who do not have at all. The challenges of having access to technology is an important one. Any democratic model becomes problematic if it is based on access to something that not everyone has access to. Lower income households lack access to computing technology. In the US, technology has become the most affordable tool. In order to maximize an online user-generated content, high-speed internet connections are required.

Hence, the faster the connection, the more able one is to participate in a crowdsourcing application. As a result, it is important that organizations consider the division between those with high speed connections and those within dial up connections. This can be done by setting up community technological centers, or the expansion of technology centers in public libraries. Ball-Rokeach (2007) argues for the maintenance of community technology centers on civic, democratic participation, and community empowerment grounds.

Another challenges of crowdsourcing is the development of the Web interface and the sustaining of an online community, such as accessibility, usability, cost, and issues surrounding the sustaining of an online community which include: timing, promotion, inc;usion, and dealing with crowd resistance. Web usability principles should be usable to maximize user experience, deliver appropriate information, and maximize kick-outs. The community becomes more vibrant through the use of a great Web. A crowdsourcing challenge requires an aggressive marketing and public relation plan in any planning project. A final challenge of crowdsourcing is knowing when to include or exclude individuals in the process, and how to deal with crowds that are resistant to crowdsourced tasks.

Conclusion

There is a need for new citizen participation methods in public planning. The use of technology will assist to enable deeper levels of engagement between residents and the governments, through the use of the medium of the Web. The crowdsourcing model is a method of tackling collective intellect and creative solutions from networks of citizens in organized ways that serve the needs of planners. There is a need to embrace the crowdsourcing model and of the Web in general by the planning profession. Planning professionals and policymakers need to take risks with innovative models such as crowdsourcing in the public involvement process of planning efforts.

References

Abram, S. and Cowell, R. (2004). Learning Policy: The Contextual Curtain and Conceptual Barriers: European Planning Studies 12(2): 209–28.

Alfasi, N. (2003). Is Public Participation Making Urban Planning More Democratic? The Israeli Experience’, Planning Theory & Practice 4(2): 185–202

Brody, S.D. (2003). Measuring the Effects of Stakeholder Participation on the Quality of Local Plans Based on the Principles of Collaborative Ecosystem Management. Journal of Planning Education and Research 22(4): 407–19.

Brabham, D.C. (2006). Noticing Design/Recognizing Failure in the Wake of Hurricane Katrina: Space and Culture 9(1): 28–30.

Brabham, D.C. (2007). Speakers’ Corner: Diversity in the Crowd. Crowdsourcing: Tracking the Rise of the Amateur, Weblog, 6 April, available online at: [http://crowdsourcing.typepad.com/cs/2007/04/speakers_corner.html], accessed 10 June 2022.

Brabham, D.C. (2008b). Crowdsourcing as a Model for Problem Solving: An Introduction and Cases. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14(1): 75–90.

Burby, R.J. (2003). Making Plans that Matter: Citizen Involvement and Government Action. Journal of the American Planning Association 69(1): 33–49.

Carp, J. (2004). Wit, Style, and Substance: How Planners Shape Public Participation. ,Journal of Planning Education and Research 23(3): 242–54.

Campbell, H. and Marshall, R. (2000). Public Involvement and Planning: Looking Beyond the One to the Many. International Planning Studies 5(3): 321–44.

Crewe, K. (2001). The Quality of Participatory Design: The Effects of Citizen Input on the Design of the Boston Southwest Corridor: Journal of the American Planning Association 67(4): 437–55.

Corburn, J. (2003). Bringing Local Knowledge into Environmental Decision Making: Improving Urban Planning for Communities at Risk: Journal of Planning Education and Research 22(4): 420–33.

Fiskaa, H. (2005). Past and Future for Public Participation in Norwegian Physical Planning: European Planning Studies 13(1): 157–74.

Forester, J. (2006). Making Participation Work when Interests Conflict: Moving from Facilitating Dialogue and Moderating Debate to Mediating Negotiations. Journal of the American Planning Association 72(4): 447–56.

Hanna, K.S. (2000). The Paradox of Participation and the Hidden Role of Information: A Case Study. Journal of the American Planning Association 66(4): 398–410.

Hibbard, M. and Lurie, S. (2000). Saving Land but Losing Ground: Challenges to Community Planning in the Era of Participation. Journal of Planning Education and Research 20(2): 187–95.

Howe, J. (2008). Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the Crowd is Driving the Future of Business. New York: Crown Business.

Hou, J. and Kinoshita, I. (2007). Bridging Community Differences through Informal Processes: Reexamining Participatory Planning in Seattle and Matsudo. Journal of Planning Education and Research 26(3): 301–14.

Ignatius, D. (2001). Try a Network Approach to Global Problem-solving. International Herald Tribune, 29 January, available online at: [http://www.iht.com/articles/2001/01/29/edignatius.2.t_1.php?page=1], accessed 11 June 2022.

Innes, J.E., Connick, S. and Booher, D. (2007). Informality as a Planning Strategy: Collaborative Water Management in the CALFED Bay-Delta Program’, Journal of the American Planning Association 73(2): 195–210.

Lakhani, K.R. and Jeppesen, L.B. (2007). Getting Unusual Suspects to Solve R&D Puzzles. Harvard Business Review 85(5): 30–2.

Lakhani, K.R. and Panetta, J.A. (2007) ‘The Principles of Distributed Innovation’,innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 2(3): 97–112.

Lakhani, K.R., Jeppesen, L.B., Lohse, P.A. and Panetta, J.A. (2007).The Value of Openness in Scientific Problem Solving Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 07–050, available online at: [http://www.hbs.edu/research/pdf/07–050.pdf], accessed 17 December 2008.

Maier, K. (2001). Citizen Participation in Planning: Climbing a Ladder? European Planning Studies 9(6): 707–19.

Mack, T.C. (2004). Internet Communities: The Future of Politics? Futures Research Quarterly 20(1): 61–77.

Masum, H. and Tovey, M. (2006). Given Enough Minds . . .: Bridging the Ingenuity Gap’, First Monday 11(7), available online at: [http://www.uic.edu/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1370/1289], accessed 11 June 2022.

Mouffe, C. (2000) The Democratic Paradox. London: Verso.

Ostwald, M. (2000). Virtual Urban Futures in D. Bell and B.M. Kennedy (eds) The Cybercultures Reader, pp. 658–75. New York: Routledge. (Original work published 1997.)

Pimbert, M. and Wakeford, T. (2001). Overview: Deliberative Democracy and Citizen Empowerment, PLA Notes 40: 23–8.

Van Herzele, A. (2004). Local Knowledge in Action: Valuing Non Professional Reasoning in the Planning Process. Journal of Planning Education and Research 24(2): 197–212.

Ripfumelo Meldah graduated from the University of Johannesburg with a Bachelor’s Degree in Urban and Regional Planning. She is currently pursuing her Honors. One of her skills is teamwork, and she has also allowed herself to interact spontaneously with diverse communities and people of all ages. She believes that architecture journalism is all about making a difference, not just in the field but also in the country as a whole.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “