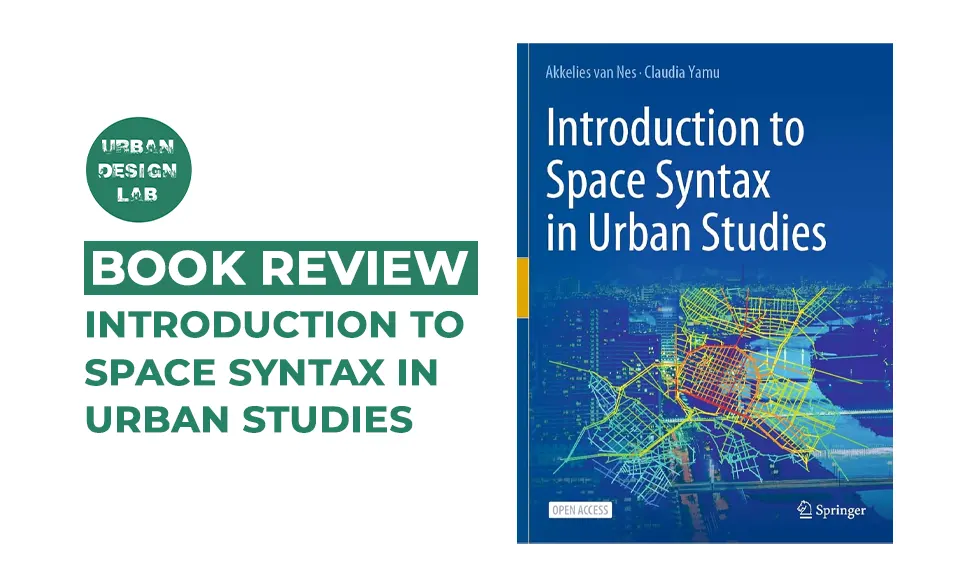

The Sustainable Urban Development Reader by Stephen Wheeler

This book comprises 36 hand-selected readings from the world’s most influential designers and activists on sustainability. The carefully curated readings are organised to create a thought-provoking journey for the readers whilst also directly catering to those who may be looking for more specific answers and ideas.

Introduction for academic book review

This book holds a collection of 36 readings from influential writers and designers with varied opinions on sustainable urban development. Many of these readings touch on their disappointment toward current cities due to suburban sprawl, pollution, overuse of automobiles, loss of natural landscapes, and inequalities. Stephen Wheeler put together this book to address the rising worldwide goal of sustainability at the beginning of the 21st century. He aimed to provoke a common question across the world: what will our cities look like in fifty years? Or better yet, what should our cities look like in fifty years? This book allows readers of all backgrounds and careers to think about how we, as a community, can develop more efficient cities that meet the long-term needs of humans and the environment.

Source: author

Overview of the book

The book is divided into seven parts, each part of which includes several relevant readings introduced by the editor. Part 1 starts with the contextual history labelled ‘Origins of the sustainability concept’, looking at what went wrong with existing cities. Part 2 discusses the broader topic of ‘Dimensions of urban sustainability’, where Wheeler provides a range of subjects involved in urban design, with the editors’ introduction directing readers to their particular interests. Part 3 is where solutions start with ‘Tools for sustainability planning’, which focuses on measuring and managing sustainability. Part 4 looks at similar urban sustainability issues worldwide while respecting the differences in ‘sustainable urban development internationally’. Part 5 is more light-hearted as it considers the possibilities for change in ‘visions of sustainable community’. Part 6 focuses on current examples on smaller and larger scales in ‘case studies of urban sustainability’. Finally, part 7 is more physical as Wheeler appreciates most people absorb more information by doing so; he finishes the book with ‘sustainability planning exercises’.

Source: author

The issues with dense urban developments

Sustainability is now crucial in design due to past design failures that led to environmental and social issues. Wheeler found that the term ‘sustainable development’ hadn’t been used until 1972 in the book Limits to Growth. It’s difficult to imagine something so fundamental in life to have not even been discussed merely 55 years ago, and that is where the problem lies. In part 1, Wheeler found abstracts of past designers aiming to deconcentrate populations of industrial cities and focus on countryside garden cities, but these activists were far too scarce. In 1891, Lord Rosebery stated he had ‘no thought of pride associated in my mind with the idea of London’ due to the dense population who had no regard for one another, let alone how much worse it got over the next century. Many advocates, including Ebeneezer Howard and Lewis Mumford, wrote some of the most potent urban development books about how overcrowded cities stunted human social and moral growth. Landscape architect McHarg wrote about his first-hand experience of returning to his hometown of Glasgow with a loss of nature and subsequent gain of poverty and grime.

Source: author

Summary of the first main argument

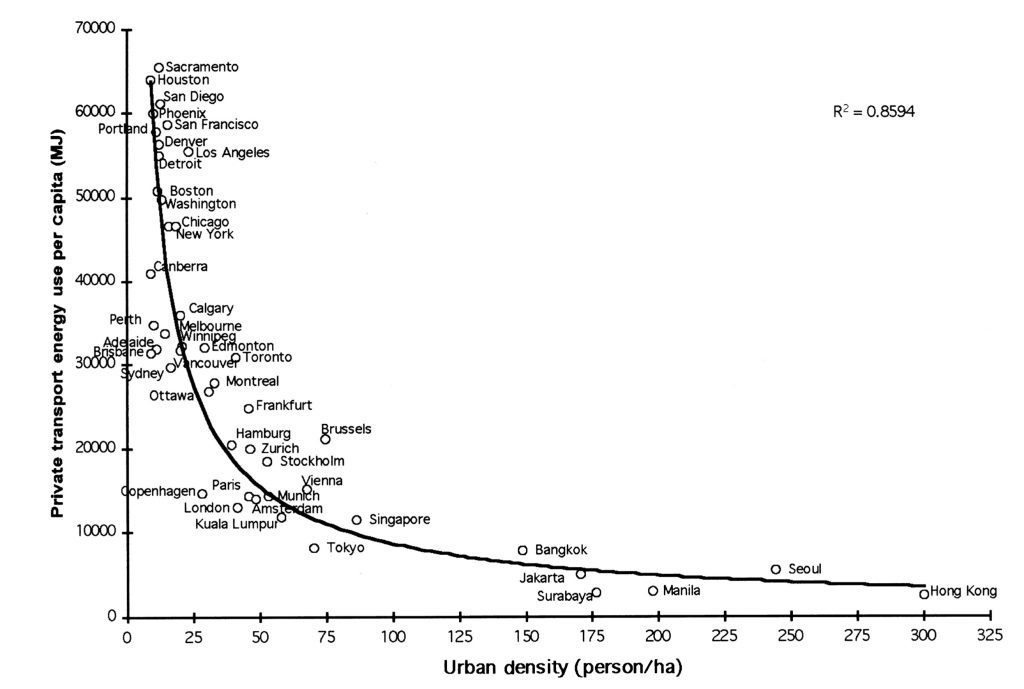

Across various parts of the book, Wheeler brings light to the individual areas of urban development, such as urban design, transportation architecture, environmental planning and economic development. When one of these aspects is pushed aside, the other areas tend to follow suit, as the readings have proved that urban development must work as a single organism. Wheeler discusses how these systems link together, and he uses a selection of readings from icons such as Jan Gehl and Robert Cervero to highlight research findings on how population and transport correlate or how outdoor spaces affect human behaviour. The readings show the importance of equity regarding race, gender and disability and how most urban developments let these people down. To begin thinking of controlling these areas, we must learn to measure their effects. The following section of the book, part 3, outlines several tools to analyse urban development and measure its sustainability. These tools include ecological footprint analysis from William Rees and Mathias Wackernagel, as well as simple first-hand observation and even constructive politics looking at long-term human and ecological needs.

Source: author

Relevance and intended audience

Many sustainability issues arise worldwide, but treating each country’s issue equally is unfair, as too many factors deviate from certain countries. To begin with, Wheeler shows how the population of developing countries grows far more rapidly than that of first-world countries, with fewer resources to accommodate it. One example given was the population of Lagos, Nigeria, which rose from 1 million in 1950 to 12.2 million in 2000, which we can now confirm reached 16 million in 2024. Part 4 of this book covers a range of readings of cities varying in wealth, climate, and population, focusing on how each of these cities dealt with sustainability issues. The information presented in this book reads that developing nations such as Brazil and its city of Curitiba have come up with more creative methods of sustainability due to their lack of resources and urgency. The innovative environment created in Curitiba is deemed much more long-lasting as it depends less on economic strength, making it all the more reliable than fortunate older European cities, which rely on many altering factors.

Source: author

Summary of second main argument

Stephen Wheeler devised a carefully calculated organisation of this book, which starts by evoking strong emotions of fear, disappointment, and maybe even anger. In part 5, he begins to lighten the book’s mood with talks of a long-term vision. This dreamy change in topic uses three fictional visions of more sustainable cities and their potential to do good in the world. This creative section induces readers to envision their own sustainable cities with limitless opportunities. Wheeler circles back to the very first reading from Ebeneezer Howard, but this time, Howard talks about his vision of the Town-Country Magnet, turning the negatives from the historical reading into this vision full of life. By carefully placing a list of current case studies from wealthy and less wealthy cities after this talk of vision, Wheeler creates a thought-provoking atmosphere for his readers to flourish with ideas when studying the various case studies. The mix of reality in part 6 and the lingering effects of visionary ideas in part 5 allows his readers to understand these urban developments’ hardships while also seeing the light and endless opportunities within them.

Source: author

Conclusion

To conclude the book, Wheeler has devised a well-planned selection of hands-on exercises that can be used in classrooms, small groups or individually. Wheeler developed the exercises in conjunction with classes taught at The University of California at Berkely. He claims these exercises are substantial enough for an entire graduate class to be structured around them. The ending of this book shows the genuine drive behind the writer himself, and his passion for sustainable urban development that he wishes to share and teach to the world. The book is structured using strong emotional readings in harmony with factual studies to keep the reader enticed. The use of the editors’ introduction of each part and each reading allows his readers to concisely carry out their research into the specific areas that concern them, all whilst catering to multiple layers of issues, tools and visions. This book recognises the differentiating hardships worldwide and across communities of different ethnicities, genders, ages and more. The inclusive nature of the book allows someone from any corner of the earth to learn valuable lessons in something that has become crucial to urban development: sustainability.

References

Wheeler, S.M., & Beatley, T. (2004).The sustainable urban development reader. Routledge.

Holly Franks

About the Author

Holly has adored architecture since childhood. Upon completing her undergraduate degree, she found that this passion stemmed from a desire to travel and explore the vast world of architecture. Since graduating from the University of East London, she has invested all her enthusiasm into starting her architecture blog and publishing online articles.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment

Senair Urban planner at Oromia Urban planning Institute