Urban Heritage of Tenochtitlan, Mexico

Introduction

Mexico City has its origins in the foundation of the Ancestral City of Tenochtitlan. Its history relates to the combination of the legends of the polytheistic religion of the indigenous culture. It is said that the Mexicas-in traditional historiography, called Aztecs- left Aztlan (the mythical homeland of Aztec culture, in northern Mexico) guided by their main deity, Huitzilopochtli, in search of “the sign”, an eagle perched on a cactus eating a snake (Embassy of Mexico, 2020). When they saw this exact scene on an island (located in what was once Lake Texcoco), it was interpreted by the Aztecs as a sign from their god, founding the City of Tenochtitlan on that island.

The foundation of Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City, was a historical event that led this culture during its splendor days, to be one of the largest cities in the world. Besides the head of the empire that ruled much of Mesoamerica, developed in parts of Mexico and Central America prior to Spanish exploration and conquest in the 16th century (Cartwright, 2014).

Mexico-Tenochtitlan

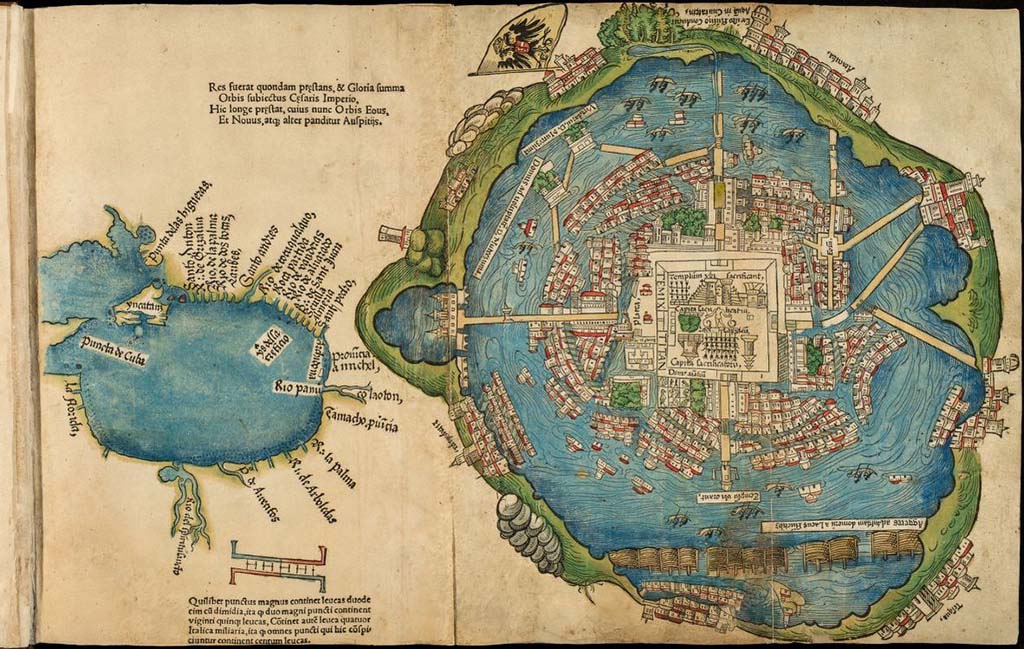

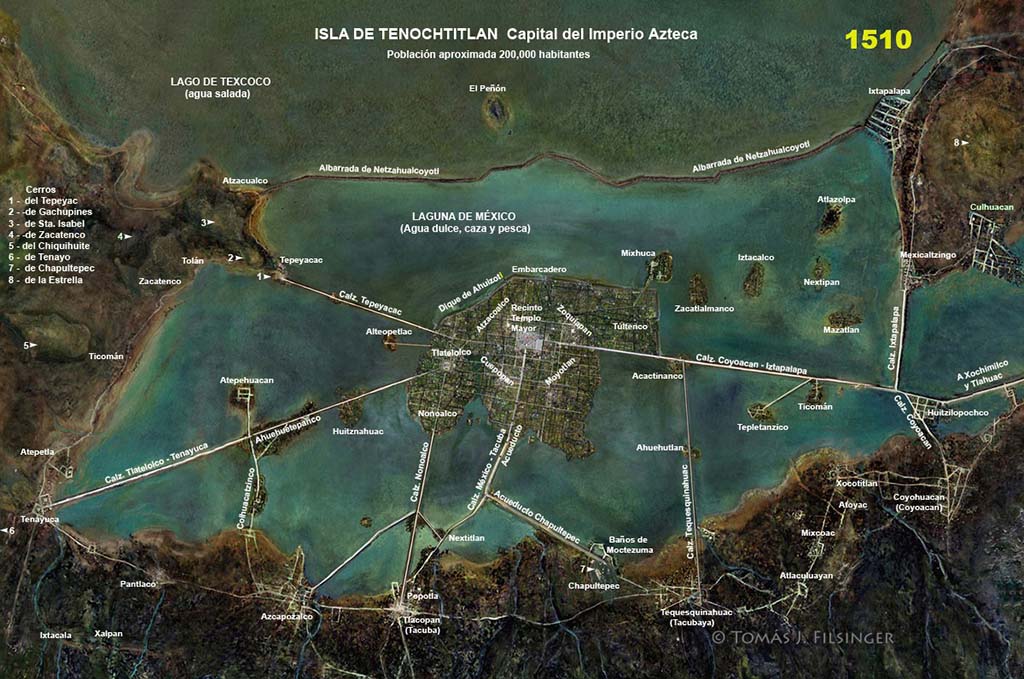

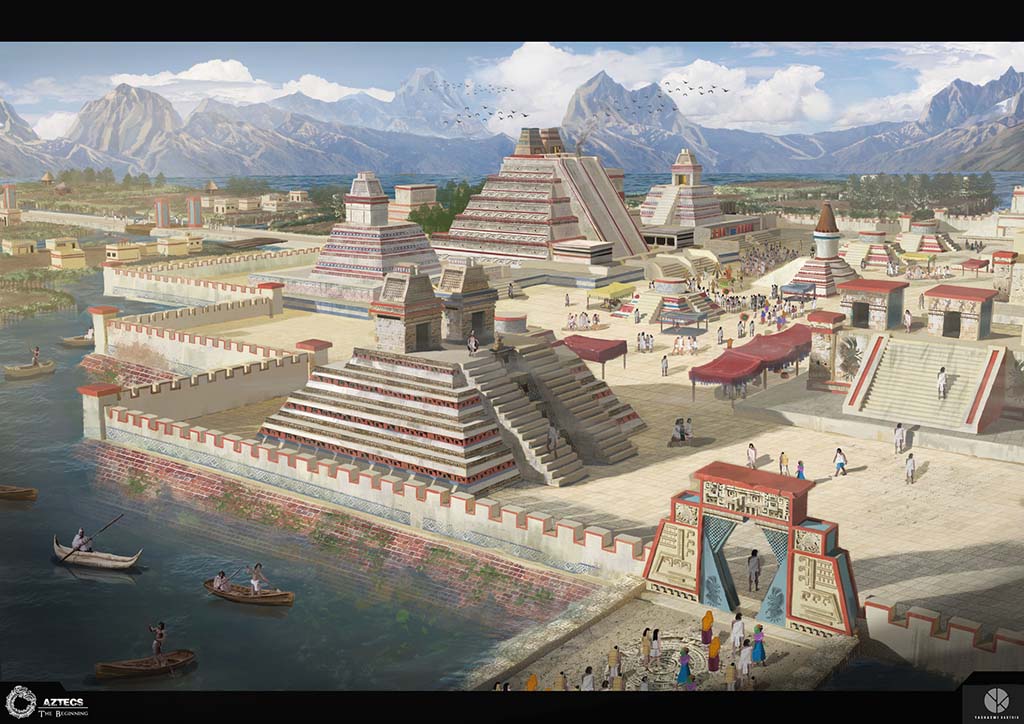

The megalopolis that we know today still preserves the original layout of Mexico-Tenochtitlan (see image below), its roads, and the towns that surrounded the lakes of Texcoco, Zumpango, and Xaltocan (D. Montecristo, 2013). Even though the conquerors wanted to bury the memory of the ancient city, its original outline continues to mark the entire flow of life in Mexico City.

Through its constructions, Tenochtitlan represented its importance as an enclave of power, along with the entrenched religious world of the Aztecs and its symbolism. In addition to these peculiarities that build it, its architecture and constructive solutions were a great lesson. Here are recover some of these innovations that the Aztecs inherited to us.

Some of the urban wonders of Tenochtitlan are the lessons that we would have to retrieve again. Since some of them are associated with the current urban avant-garde (such as the practice of urban agriculture, e.g., Image below). From the use of materials to the idea of monumentality, the heritage of the Aztec empire’s capital gives important lessons in construction and urban planning to the world.

The city on a lake

The city of Tenochtitlan was built on a lake by the ‘sign’ of the Aztec god, according to Aztec legend, and was respected even though it represented a great challenge for this culture. Therefore, the difficulty of the terrain forced the Aztecs to solve foundation problems, especially for large buildings, in an ingenious and effective way. The proposed system was through stakes of five meters buried in the ground, covered by a layer of Tezontle -the stone that became popular for its ease of carving and its lightness- as a cement.

Saving the difficulties that the subsoil offered, this magnificent work that we still have traces, it remained stable although with settlements as large as 6.5 m, until it was razed by the conquerors to build various colonial constructions on them. Precisely when the government buildings and the religious temples of the colonial conquest were developed, many of them over the very ruins of the Aztec constructions (see image below). Besides, created a complex history of loading and unloading as well as pre-compressed zones generated in the subsoil. These mentioned before, resulted in the induced variation of the mechanical properties of the subsoil, and consequently the appearance of differential settlements in those and in the current constructions of the Historic Center of Mexico City (Mendoza Lopez, 2007).

1. Hydraulic technology

Concerning supplying the city with drinking water, a transportation system was created from the existing springs (Chapultepec, see Image below) which gave way to the construction of an aqueduct. Similarly, the Aztecs designed canals to irrigate the fields and created a dam that protected the city from flooding during the rainy season (Tavares, 2011).

The Aztecs built two large aqueducts (each had two channels). While one of the channels remained in operation, the other received maintenance. Therefore, the water from these aqueducts was vital to perform daily activities since it was used mainly for the thorough and daily cleaning of the Aztecs.

2. Water for the inhabitants

Although few know it, Texcoco was made of salt water, which is why the Aztecs had to supply themselves with pure water. Subsequently, to accomplish the supply, they built dams that concentrated the water of the rivers that fed the great lake.

3. Artificial cultivation system.

One of the greatest ancient heritages of Tenochtitlan was the Chinampas, a kind of artificial islands – world agricultural heritage by the FAO – that were used to cultivate, but with the possibility of obtaining a double production given the constant presence of land and water. For its construction, a framework of trunks and rods was made from dirt and deposited with various biodegradable materials.

4. Urban Agriculture

Crops were made, both on land and in the famous Chinampas – which were floating crops. The chinampas were supported by piles; They were thick layers of earth irrigated with ditches that reached where they were placed. Other irrigation systems they devised were dams (made of wood, stone, or mud), dikes, and rainwater reservoirs. It was a city that practiced fabulous urban agriculture; the city itself supplied its inhabitants (Redaccion, 2017).

Urban Planning

It should be noted that under the same logic of the urban grid layout of Teotihuacan, the Aztec city was joined by four main roads, oriented by the cardinal points, and the Chapultepec aqueduct. In addition, a series of canals crossed each other to make right angles to divide the city into four quadrants.

1. Urban Planner

The structure of the Aztec Government demonstrated to be meticulous and cautious of the urban design and planning of their city. Due to the importance of maintaining the structure of the city, and conservation of open spaces, the existence of a crucial authority called Calmimilocatl was required. Belonging to that character the jurisdiction of preventing invasions in streets and canals for public use. Because of the disorderly practices of the current street vendors, his constant supervision of the constructions prevented them from invading the streets and canals. Thus, there was a constant review to prevent the city from losing its symmetry.

2. Transit through the city

The streets (tlaxilacalli) were effective for the transit of the city. These were built on rammed earth and used mostly for human transit. Also in some adjacent streets, a canal was made where canoes traveled.

Undoubtedly, the importance of bonding with organizations and institutions is based on showing the willingness to find common concerns and goals of contributing to society. According to the Sen Sos Habitat team, some of the Mexican government secretariats have been allies, serving as a medium between the needs of the population and the government due to the similar objectives of upholding and facilitating the interventions in many cases.

In so far as their methodology, it is important to mention, the significant task of creating collectives so that actions do not remain in individuals. Since the transmission of ideas through the community, it is wider it has a willingness the connection with society and makes it accessible to the understanding of the public.

3. The neighborhoods

The city was first divided into altepetl – a sovereign sociopolitical unit – and then into the famous calpullis, which means “big house” (neighborhoods). There were 4 main calpullis: Cuepopan (to the northwest), Aztacalco (to the northeast), Moyotla (to the southwest), and Zoquiapan (to the southeast), and to the north the great Tlatelolco (certain archaeological remains suggest that it was even older than Tenochtitlan).

These units were internally stratified and under the authority of a noble chief. The organization was established by a chief, a community leader whose main function was the administration of the land and the registration of the crops, while he made decisions on other issues, with the help of a council of seniors.

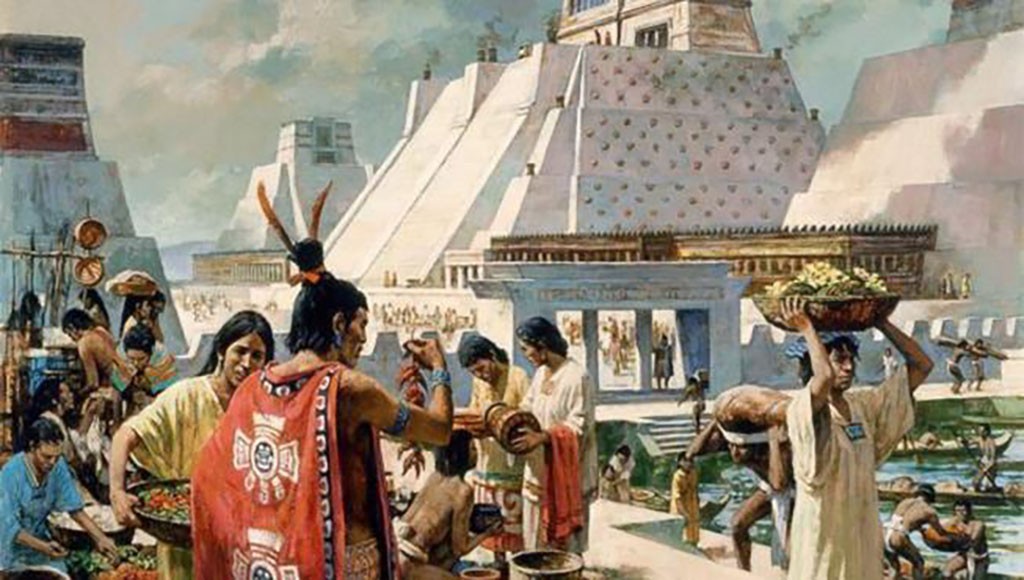

Each calpulli had its area of arable land (communal land) where everyone shared the crops and the work, it was also a way of generating social cohesion among the neighbors, as shown in Image 9. Each calpulli also had a school and an open-air market Bazar (tianguis). Although the largest and busiest was Tlatelolco, with up to 40,000 attendees on holidays and 20,000 on a usual day, according to reports by Bernardino de Sahagun.

Pyramids: World view

To the Aztec culture, using a square platform structure was transcendental since they were linked to their worldview and religious practices. The shape of the buildings referred to the mountains, source of water and fertility, and abode of ancient spirits. Most of them followed a general pattern with a platform, a long double staircase, and balustrades on the sides of the steps. What’s more, carved stone blocks and skulls (see Image below of Sanctuary), were used on the platform and at the end of the balustrades. The parts had plateaus on which a temple or the sacrificial stone of a temple was built.

1. The heart of the Empire.

The most important enclosure, called Templo Mayor, was considered the Aztec universe and was the most important religious building. It was the heart of the city and was believed to be the link between the heavenly world, the earthly world, and the infra world.

As well as its pyramidal structure, which was designed under mystical-religious beliefs, it was raised on a rectangular base on which a base of four bodies rested. The base was decorated with carved figures. The performance of sacrifices involved a series of elements found on the main altar of the Great Temple. In the middle part, two stairways led to the shrine of the god Tlaloc (supreme god of rain), and Huitzilopochtli (Aztec god of the sun and war). As well as other temples in Mesoamerica, the four sides were enlarged at least seven times, during the different governments, to show the contribution of each ruler – tlatoani -, thus the buildings were built one on top of the other (King, 2004).

2. Temples

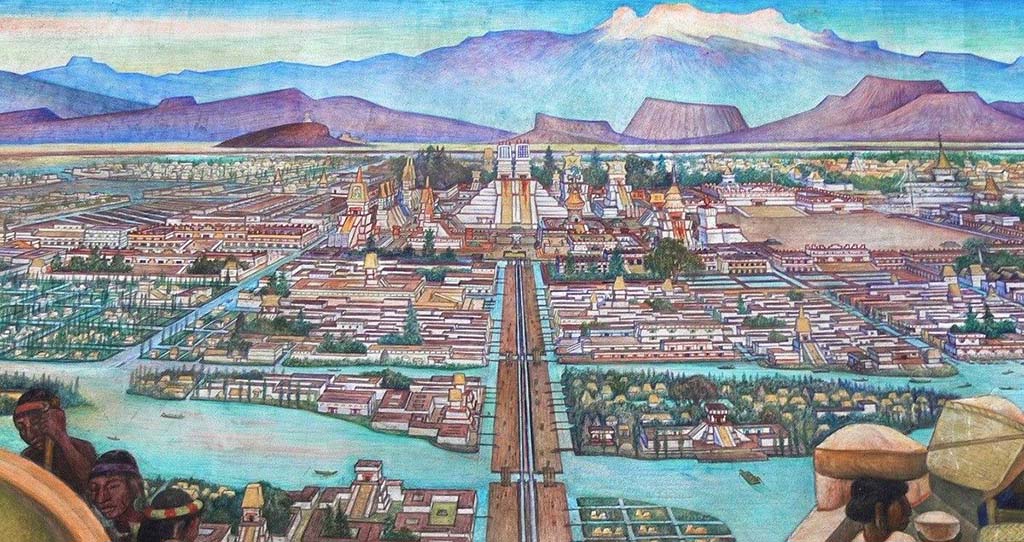

The Aztecs built 25 pyramid-shaped temples. With the intention of reproducing the silhouette of the mountains and emulating in their temples the rite of ascension to heaven. They also made pyramidal objects for home use, transferring their rituals to the private sphere as well. A Pictographic recreation of the aerial view of the great Aztec city and its splendid lakes is shown in the image below.

The benchmarks are:

- Ceremonial Center, Templo Mayor

- Commercial and ceremonial center of Tlatelolco

- Road to Tlacopan and Tacuba

- Causeway to Tepeyacac

- Causeway to Iztapalapa and Xochimilco

- Cerro del Peñon partially submerged

- Albarrada of Netzahualcoyotl

- Lake Texcoco

- Lake Mexico

- City of Texcoco

3. Spotless City

There were up to a thousand people in charge of cleaning the streets that were swept and cleaned daily. There were also macehuales– an aboriginal group that was part of Aztec society and occupied the third step in the social structure-, dedicated to collecting excrements to later sell them as natural fertilizer or they were deposited in private or public latrines. The garbage, meanwhile, was incinerated in huge bonfires that served to illuminate the streets at night.

The great Metropolis heritage.

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in 1521, the city of Tenochtitlan had 60,000 active canoes, and 50 large buildings that stood out from the one-story houses, the calpulli neighborhoods had their own communal land, markets, and the education of the schools was free for all children. It is estimated that approximately 200,000 inhabitants lived there. Positioning Tenochtitlan as a powerful metropolis, and larger than any other European city.

The life of the city was perfectly organized and had engineering solutions that continue to surprise scholars to this day. Especially if we consider that most of the city was built and flourished on an islet surrounded by brackish water.

Along with the environmental contributions, the traditions and culture, and hydraulic engineering solutions, today this ancient city is worthy of a heritage that should be reviewed as a sustainable option to affront challenges that our society faces in the 21st century. As well as the magisterial inheritance in the urban agriculture contributions, hierarchical and social structures, respect and attachment to nature and active participatory community in the activities of the city. Today most of these contributions have been lost, but the heritage is documented and the evidence in the archaeological sites shows us what life was like in the city of Tenochtitlan.

However, during the three centuries of the Colony after the Spanish conquest, the flooded areas were systematically dried out, losing groundwater until the ditches were eliminated. Thereby, many of them today become avenues through which modern transport systems circulate. Only those canals with trajineras, at Xochimilco, remain iconic places that preserve activities related to the heritage of this millenary culture.

References

Embassy of Mexico. (2020, September). Symbols of Mexico. Embamex. Retrieved June 24, 2022, from https://embamex.sre.gob.mx/reinounido/images/stories/PDF/Meet_Mexico/2_meetmexico-symbolsofmexico.pdf

Cartwright, M. (2014, February 26). Aztec civilization. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 24, 2022, from https://www.worldhistory.org/Aztec_Civilization/

Mendoza Lopez, M. J. (2007, September 20). Comportamiento Y Diseño De Cimentaciones Profundas En La Ciudad De México. Mexico; https://www.construccionenacero.com/sites/construccionenacero.com/files/u11/ci_34_34183_comportamiento_y_diseno_de_cimentaciones_profundas_en_ciudad_de_mexico.pdf.

Redacción, R. (2017, July 13). El sistema de chinampas es reconocido Como Patrimonio Agrícola Mundial Por La Fao. Más de México. Retrieved June 24, 2022, from https://masdemx.com/2017/07/chinampas-mexico-patrimonio-agricola-mundial-reconocidas-fao/

King, H. (2004, October). Tenochtitlan: Templo Mayor. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–Retrieved June 24, 2022, from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/teno_2/hd_teno_2.htm

Mexican researcher that holds a Bachelor’s in Architecture from the Veracruzana University, and aspiring Urban Planner at the Spitzer School of Architecture, New York. Enthusiastic about solutions based on nature, and organic transitions between the natural and the urban realm. She is passionate about art, the natural environment, and its effect on the human psyche.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

2 Comments