Urban voids: A misunderstood resource of the contemporary city

The city building process is a highly complex phenomenon consisting of enormous numbers of collective efforts. These efforts can translate into successful or failed developmental projects, depending on the degree of motivation and robustness driving them. But there are some other cases where a successful project becomes outdated, invalid, or not in use anymore. These empty spaces in cities form vacuums or blindspots of some sort. In mainstream urban design theory, these spaces are termed “urban voids.” As a relatively new urban term, it is also a space which is addressed in an almost utopian manner and reimagined for the bourgeoisie of the city.

Discrepancies in the Definition

First talked about by Jane Jacobs in her book “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” in Chapter ‘Curse of Border Vacuums’, the book focuses mainly on the symptomatic phenomenon of land-uses forming borders of immense vacuums which suck out life from the urban elements of a city. If we look at other definitions given for the term “urban voids,” a number of urban design theories have exhaustively defined it. According to Abraham and Ariela (2010), these voids are spaces that are found outside of common urban peripheries or borders. While Narayanan (2012) defines urban voids as spaces without “permeability” and “public realm,” Jonas & Rahmann (2015) view urban voids as both gaps and leftover buffer zones in a city. They do not have any functions or boundaries. They are viewed as unsafe and are also home to illegal activities.

Often these explanations have been taken as absolute by practicing designers, planners and institutions, making it very hard to evolve into a nuanced topic. Major discrepancy comes when these theories are translated into the context of the Indian subcontinent. Here, things are much more complex as these urban voids which are termed as vacant land resources are not vacant in the real sense. They are thought to be occupied by illegal parking, waste disposal and in some cases criminal activities. But the urban poor also occupy them for a number of reasons, such as-

1) Taking shelter and refuge from the weather (rain, cold, heat etc).

2) Carrying out informal vending activities for sustenance of their livelihood.

3) In case of a mass urban catastrophe like in Covid, the informal workers are forced to stay out in the open.

The bourgeoisie approach

If we look at the history of social change in the last 60 to 70 years in the great big cities of the world, we can find the bourgeois leading the path of that social change. It is not necessary for these changes brought about by the bourgeoisie to be in favour of everyone in the city. Though the changes have brought issues regarding the inclusivity of the urban poor, Only in the last 30 years for the rest of the world and 10 to 20 years for India, has the topic of inclusivity been seriously looked upon. In practice, it is hard to say if there has been a truly inclusive approach towards city building today. This component of the city-building process (the Urban Void) has a similar history. As recently as in the latter part of last decade, this topic has come up in discussions around urban development. And this approach has also been led by the Indian bourgeoisie (upper middle class) of the metropolitan cities.

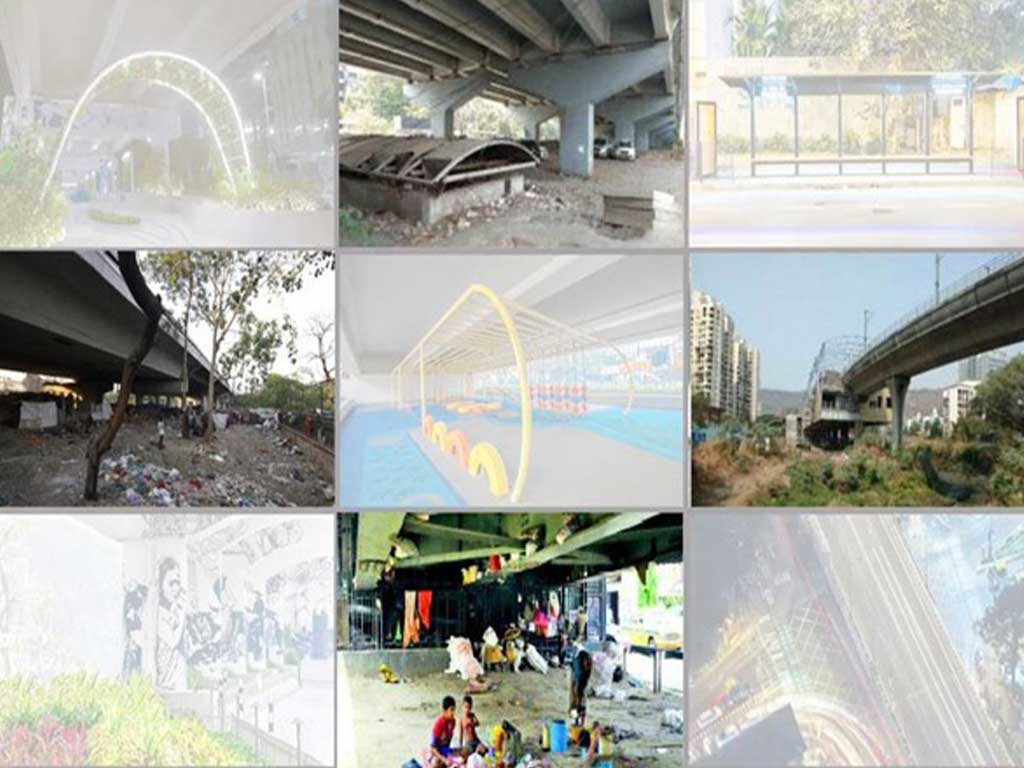

1) Mumbai, Matunga Tulpule Flyover

The Tulpule Flyover project starts with the issue of traffic management, threatening pedestrian safety, illegal parking, and the setting up of informal stalls. The residents nearby, who pride themselves on being the cleanest neighbourhoods in Matunga (Mumbai), initiated a bid to prevent encroachment by illegally parked cars and more so, “beggars”. Residents first approached the MCGM (Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai) and local police to barricade the area. After this, a design was submitted to MMRDA (Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority) clearly showing exactly where local residents want to set up programmes and reclaim their public realm. But how inclusive is this public realm?

2) Mumbai, Senapati Bapat Road Flyover- One Green Mile

This project sets up its need to be a haven for the space-starved locals who have long been fighting pandemic fatigue. The so-called gardens are designed to include a library, a children’s play zone, a green aisle, as well as exercise and recreational zones. The project claims to provide a pause of relief for over one lakh commuters who navigate the area amid heavy traffic, and the greenery provided is supposed to serve as a welcome sight for sore eyes. Not only does it follow in the footsteps of the Tulpule case, but it takes it a step ahead, becoming an economic instrument rather than an earnest step towards making a truly inclusive public space, as the project calls itself one of the pioneer PPPs (Public Private Partnerships) in the urban infrastructure realm, which will bring new investors to the city.

This project, which was inaugurated as recently as January 2022, shows us how the public realm is still dominated by the aspirations of the privileged and theoretical terms that were derived from the social sciences, such as spatial justice and spatial equity, which are still just in theory. The credit for this mostly goes to the designers, architects, and planners who have so righteously held on to these theoretical terms until a real opportunity for change comes along, and all that is focused then is the completion of the project and the economic benefits associated with it.

Can urban voids truly become inclusive and empathetic public spaces?

There are definitely efforts in this direction, in the form of proposals and projects initiated by a few municipalities, NGOs and academic institutions. These entities consider an array of activities to attract users from surrounding communities, more dynamic and interactive programs formulated to activate the public realm which consist of cafes, food stalls, small business enterprises of the communities, and occasional weekly activities. The activities aspire to be distinctively unique to the locality’s requirements. So, the area can be allowed to expand with some space for the urban poor to become a part of this exercise too, and create places with rich identity rather than homogeneous spaces of traditional planning.

1) Ahmedabad Vision- for design of spaces under flyovers

Here, the vision demonstrates how presently neglected spaces beneath flyovers can be utilized to augment inadequacies of the existing conditions and become vibrant community areas. The space between supporting pillars can be used for multiple activities during the day and night. Assuming that the present insufficient width of the roads alongside the over bridge will be revised to include designated cycle tracks and pedestrian pathways, helping to make the new community spaces more accessible and linking them with the nearby Dharnidhar BRT station. Communities around each flyover will be able to decide their own needs & priorities, so as to convert the areas below the flyovers for uses complimenting their collective aspirations.

2) Makeshift schools under Y.K. Jhuggi camp flyover, Yamuna Khadar area of east Delhi

The vision for these makeshift schools came out of the observed need of a young student, accompanied by 25 other enthusiastic volunteers to empower the children staying in Y.K. Jhuggi camp slums by providing them with education. Though the efforts may seem small in comparison to the expensively redesigned public spaces for the gated residential communities and the corporate workers, it has brought tiny social change within the laborer parents of the children to invest money to purchase stationery. Many people from the area have donated boards, chairs and books participating in the process of better infrastructure building for the learning environment.

Conclusion is long way ahead

The discussion around the tokenization of these kinds of infrastructural redevelopment projects is in its nascent stage. It is imperative to note that neither the hyper-capitastic way nor the social activism way to approach this problem is advised in this article. But a good look at both and creating new solutions, probably hybrid ones are necessary to be researched and developed in its justified urgency so we might invent what Jane Jacobs was striving for all along, i.e. a city with lesser vacuums and more social inclusivity.

References

1. Kasarabada, D. (2020). Urban Leftovers: Identifying and Harnessing their potential for the Agenda 2030 in Malmö, p. 26-31.

2. Bhaskaran, R. (2018). URBAN VOID- A ‘BYPASSED’ URBAN RESOURCE, p. 3-5.

3. Katkar, H. (2021). INFRASTRUCTURAL URBAN VOIDS AS AN INSTRUMENT FOR HOMOGENOUS URBAN FABRIC CASE OF KHARGHAR

4. ITDP. (2013). Visions of Ahmedabad

About the Author

Anubhav Borgohain is an architect/urban designer working in the field of urban research, specializing in resilience urbanism. He has recently worked on the ‘Rising water, Safer Shores, the BReUCom project with the Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation- ITC University of Twente , focusing on dissemination of urban flooding preparedness through game development. He has recently presented at the International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies (conducted by I.C.O.M.O.S., Austria, Nov. 2021) and in the First International ONLINE conference on Pandemics and Urban Form, PUF2022.

Related articles

Emerging Technologies Reshaping Urban Planning

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “