Planning Post-War Ukraine: Transforming Crisis into Urban Development Opportunities

Ukraine has been faced with numerous crises in the last few decades: Chernobyl, post-Soviet restructuring, corruption, and now the War with Russia. How can this collection of crises be dealt with effectively and where can pathways toward progress be made in the midst of such violence? Several options toward rebuilding and redevelopment of Ukraine in the future are available: field research, preservation, modernization, economic shifting, strengthening international relations, and rebuilding solid community foundations.

Overview of Political and War Crisis

Since 2022, global attention has been fixed on the crisis of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The country has taken the physical and social tolls of warfare, with infrastructure, architecture, and communities damaged or destroyed. Progress in the development of the ex-Soviet state has halted and in some cases reversed. Resources and funding have been diverted to fighting on the frontlines and maintaining the wellbeing of population centers. In a Europe often defined by crises, Ukraine seems to be taking center stage.

Despite the overwhelming challenges of ending warfare and corruption, Zelensky has offered great courage and hope to residents of the country. His usage of social media, ground work, and foreign policy have given much needed encouragement to a battered people. In line with this hope narrative, several organizations and civil leaders have begun efforts aimed at rebuilding Ukraine in the post-War future– whenever it may arrive.

Paths Toward Recreating Ukrainian Places

Groups like ro3kvit and Mariupol Reborn have started serious initiatives to reconstruct and establish major cities. The former is an organization funded by the Swedish Institute and has been offering courses on urban design and rebuilding aimed at supporting Ukraine’s future economic integration into the EU, such as its “Rapid Urban Re-Innovation” project [1]. The latter has teamed up with professors at MIT to offer civic leaders and architects lectures on the most up-to-date research and approaches to rebuilding the economy and engaging in the international market [2].

Many more such projects exist, and while this offers a refreshing and hopeful vision for the future, it also raises some concern. How will these different groups with sometimes contrasting goals cooperate in the future? How will Ukrainians know which steps to take and when? Planning research offers some basic guidelines for such concerns.

Source: Website Link

Step 1: Establishing Needs and Goals, For the Immediate and Future

According to a February 2025 United Nations report, the current problems Ukraine has begun paying for are “housing, education, health, social protection, energy, transport, water supply, demining, and civil protection.” This has already cost the country over €7 billion, and total reconstruction costs are estimated to reach past €500 billion [3]. As buildings are continually destroyed and infrastructure left unrepaired, Ukrainian officials are stuck in a dilemma: there is a need for large structural projects, but no clear source for funding. To add to this, the economic politics of Ukraine have historically involved much political corruption, raising an understandable amount of caution from those planning for the post-War period.

But, this era of crisis also opens opportunities for sober-minded reforms to take place. Better internal and external affairs should be part of this process, and would doubly aid in economic revitalization. Stronger government, organizational, and community relations must also be established. Thus, the main concerns moving forward for Ukrainian rebuilding are: infrastructure, economics, international relations, anticorruption efforts, and community empowerment.

Step 2: Gathering Data Through Research and Field Studies

As architects and planners begin to assess the damages done to neighborhoods and historic sites, researchers must review data to determine the best approaches to post-War reconstruction. Resulting academic works will be useful in determining next steps.

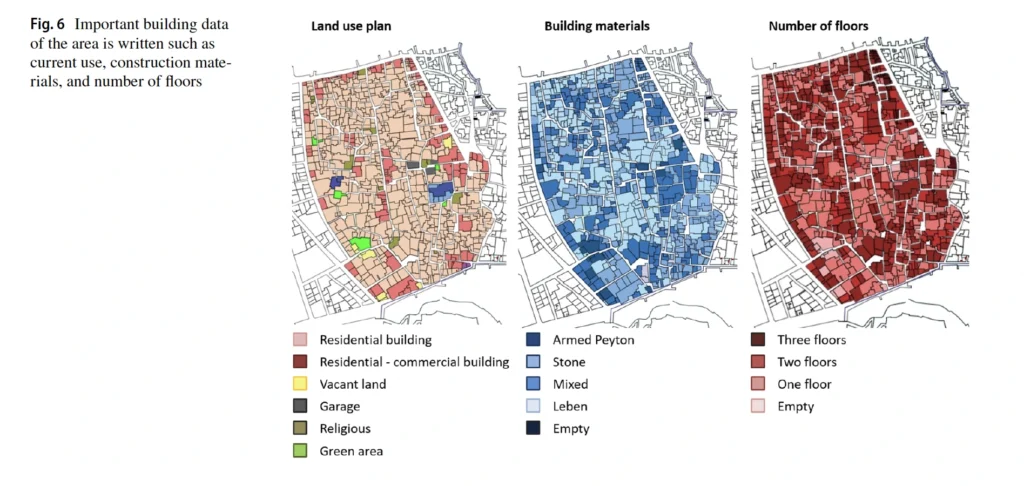

Data on urban areas will have to be gathered from a plethora of sources. Government records, academic papers, historic texts, and field research will all need to be applied. As rebuilding involves applying both the hard and soft science, a good mixture of quantitative and qualitative data will be utilized. Some specific approaches which would best suit architects, engineers, and designers would be field analyses of damaged sites; studies of traffic flow in recovering areas; and multilevel GIS mapping of integral sites, where the differing characteristics of separate areas are clearly labelled (based on building type, level of damages, density, etc.) [4].

As for planners, social workers, and community leaders, surveys should be taken on the best approach to rebuilding; maps of social networks could be compiled and used in community development efforts; efforts of grassroots organizations should be studied (and, when appropriate, supported); and research gathered on particularly relevant issues.

Step 3: Analysis of Data Through Different Approaches

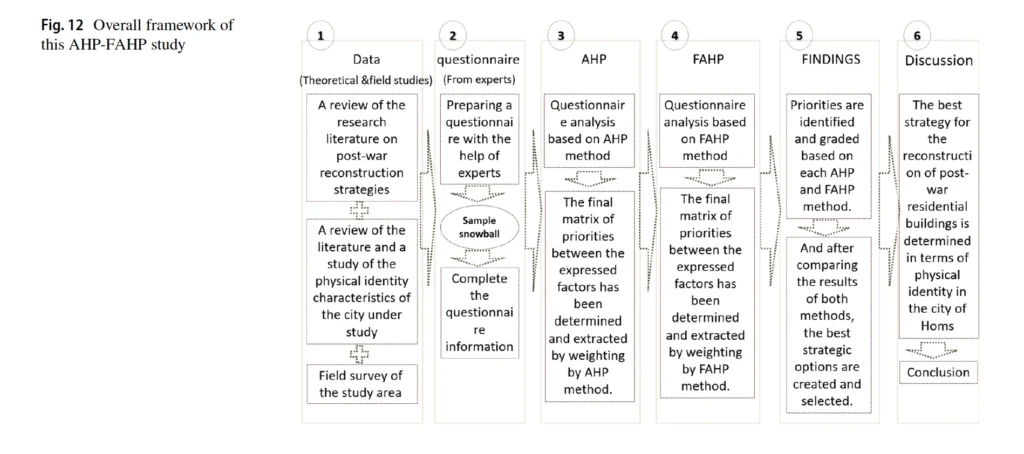

Once sufficient data has been gathered, several approaches may be used to synthesize, analyze, and use findings. One especially helpful approach was used by researchers during the rebuilding of Homs, Syria. This approach involved considering “approximate area, construction materials, age of the building, current condition, shape of the surface, number of floors and general notes” and then building a ranking system from which to judge the importance of the different issues discovered [4].

The researchers in this case used a Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process, which aided in appropriately synthesizing quantitative and qualitative data. The resulting hierarchy of desired outcomes from a rebuilding project were then analyzed for application; in the case of Homs, people primarily desired buildings in the area “to retain their historic status and rebuild them in the same style” [4]. In this example, architectural integrity was the focus, but the approach and models used are applicable to a wide variety of issues facing Ukraine, from infrastructure management to social services.

Step 4: Applying Different Types of Rebuilding

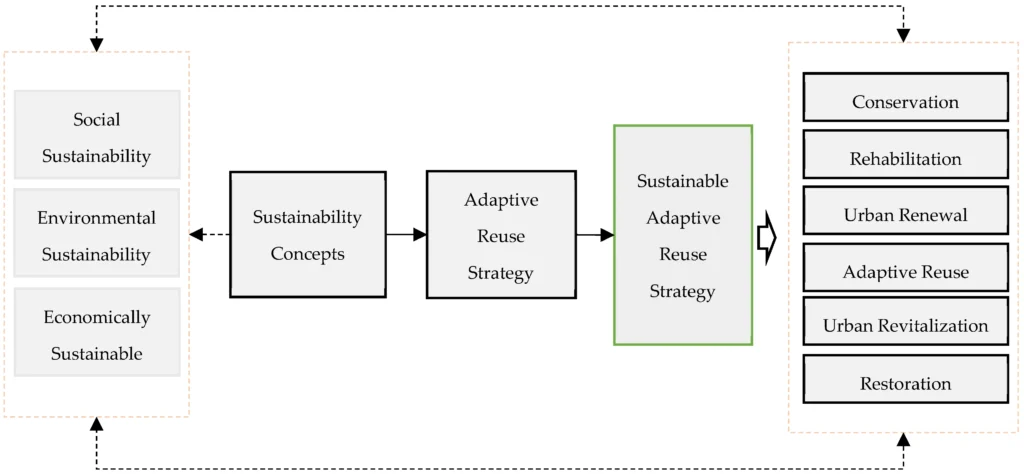

Three primary approaches to rebuilding are: Restoration, Renewal, and Regeneration. Through Restoration, projects are rebuilt as-they-were, with careful attention to historic context and value. This was the approach of some of the cities in the aftermath of the Second World War. As Ukraine holds many valuable cultural sites, the knowledge of artists, architects, and historians will play an important part for this approach[4].

Renewal projects aim to replace or update buildings with more modern materials or structures [4]. Preserving obsolete and overpriced architecture, or building out-of-context structures are both pitfalls to avoid. The need for quick and cheap buildings during such a crisis should not lead to cutting corners in design and materials, but to finding creative solutions which equitably benefit all Ukrainians.

Projects for Regeneration are ones (re)built with careful attention to context, but utilizing public participation with the goal of environmental (ecological, social, economic, etc.) improvement. Many projects in the foreseeable future will likely fall under this category. This approach is marked by a strong sense of rootedness by locals working on the developments in their own neighborhoods. The hope is to not just rebuild, but upgrade and reignite a neighborhood [4].

Step 5: Methods for Taking Action

As previously mentioned, social media has been a huge contributor to the hope narrative in Ukraine [5]. This form of face-to-screen-to-face interaction has allowed for immediate communication with mass amounts of Ukrainians. It allows citizens to feel at level with leaders during briefings or announcements. If rebuilding is going to come top-down and bottom-up simultaneously, this will be an integral tool to that end.

One organization called Re:Create UA offered architects the chance to redesign several buildings which had been damaged across Ukrainian cities. Winning renderings were supposed to be displayed, then reworked into real projects, but the project unfortunately seems to have gone defunct [6]. Some architects have also considered how cities like Warsaw rebuilt in efforts to plan for Ukraine. Survivors helped resettle and reconstruct after World War II, often using found materials in the process. One notable feature was the use of “rubble concrete” in construction [7]. Not only was this a very sustainable move, it helped people move on from the War while literally cementing past events into the structure of Warsaw. As Ukrainians seek a new future with the EU, they may consider similar actions.

Current Ukrainian Approaches to Urban Redevelopment

As mentioned, several rebuilding initiatives have already begun. The Handbook on Post-War Reconstruction and Development Economics of Ukraine (2024) offers several economic development pathways for Ukrainian cities to take. A few suggestions include: investing in railway station complexes (RSCs) which are combined business, commerce, and transit centers, popular across Europe; forming comprehensive cadastral map systems for recording detailed real estate and land data; investing in sustainable tourism campaigns; utilizing a “social organization and planning framework” for inclusive redevelopment; and making systemic revisions in both market and government [8].

Rebuilding as a Communal Process

Dyak (2023) suggests that continuity between the pre-War and post-War conditions of places is crucial for the healing process of cities and towns. She writes: “The work of making these connections, relating to both lost and emerging built environments, will be crucial in reassembling communities, in place or at a distance… Therefore, it feels important to create archives that will accommodate diverse, different, marginal and even dissonant experiences. Telling about the war will be a part of recovering, taking many years and many stories” [9]. Rebuilding is not just a physical, but a deeply cultural process, and will take much personal and communal processing.

Many in the architecture community have stepped up to offer solutions to the immediate problems– notably the housing crisis. Constructing Hope: Ukraine was a 2024 exhibition tour, showcasing the work of architects tackling the issues of sheltering and rehousing. Aspects of wartime life, such as taped windows, were integrated into designs. A “ready-to-assemble” bed for displaced peoples was also presented as a practical approach to meeting needs [10].

Conclusion

These present projects are valuable not only for efficiently providing resources, but also for fostering a sense of hope and resilience among Ukrainians. Such hope will be the driving force toward a better future for this part of Europe, in its aspirations to find peace, prosperity, and welcome to the European Union.

References

- https://ro3kvit.com/projects/rapid-urban-re-innovation

- https://news.mit.edu/2025/rebuilding-ukraine-0226

- https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/02/1160466

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41024-023-00268-4

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781394180844

- https://ukrainianpost.com/culture-entertaiment/297-creativity-that-restores-cities-visit-the-updated-site-re-create-ua

- https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=Architects+look+to+Warsaw+for+lessons+on+rebuilding+Ukraine+from+rubble&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8

- https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-48735-4

- https://journal.eahn.org/articles/10.16995/ah.9805/

- https://www.centerforarchitecture.org/exhibitions/constructing-hope-ukraine/

Patrick Melo

About the Author

Patrick Melo has a B.A. in Anthropology from Wheaton College (IL). He was a student leader in the International Students Program and is part of the Lambda Alpha National Anthropology Honor Society. He is CITI certified for human research and has conducted two undergraduate ethnographies.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Best Landscape Architecture Firms in Canada

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “