Wetlands as an infrastructure for wastewater management

Due to water-scarcity challenges around the world, it is essential to think about non-conventional water resources to address the increased demand for clean fresh water. Among the current treatment technologies applied in urban wastewater reuse for irrigation purposes, wetlands were concluded to be one of the most suitable in terms of pollutant removal and have advantages due to both low maintenance costs and required energy. Wetland behavior is integrally related to efficiency concerning wastewater treatment. Though this is rediscovered recently by scientists, this process has been present for a long time in indigenous waste management vernacular. The article will explore these examples and their typologies.

Introduction

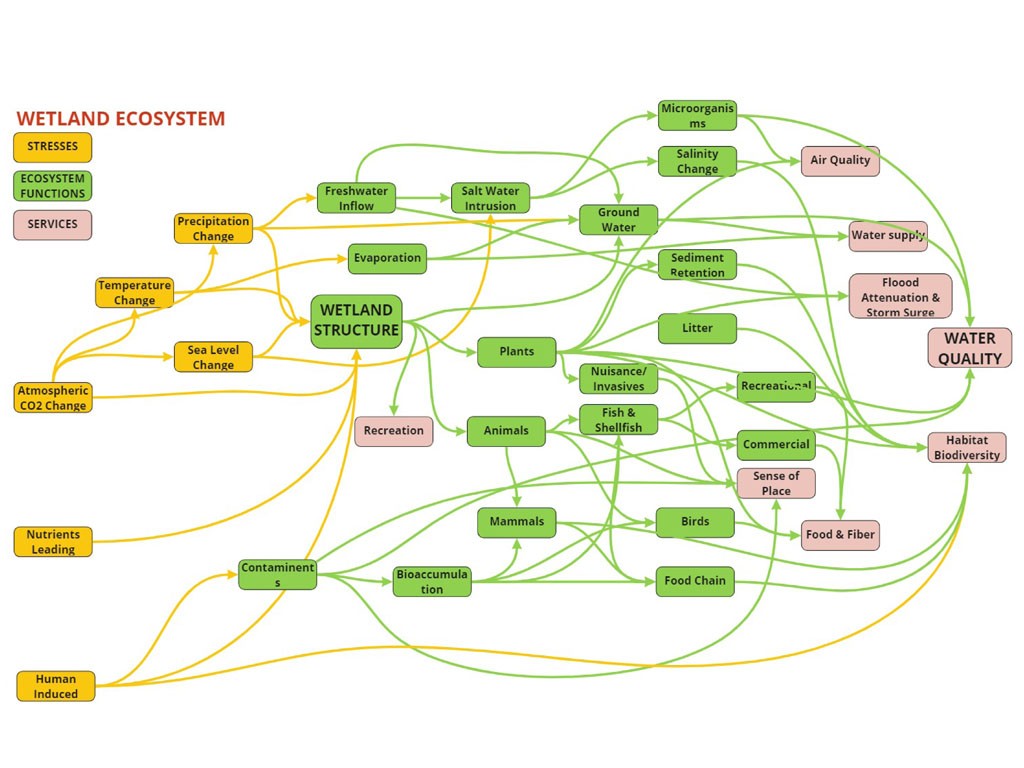

Wetlands are widely recognized as transitional areas between terrestrial and aquatic systems. They provide multifunctional benefits, most prominently relating to the ecosystem, the economy, and scenic quality. They are one of the maximum productive ecosystems that support various habitats and are known for their diverse goods and services ecosystem.

The capacity of wetlands to absorb a great number of water benefits developed areas, especially during periods of flooding. Wetland systems can also protect shorelines, recharge groundwater aquifers, and cleanse polluted waters. They have been described as “the kidneys of the landscape”, as they can affect the export of organic materials and serve as a sink for inorganic nutrients and atmospheric carbon.

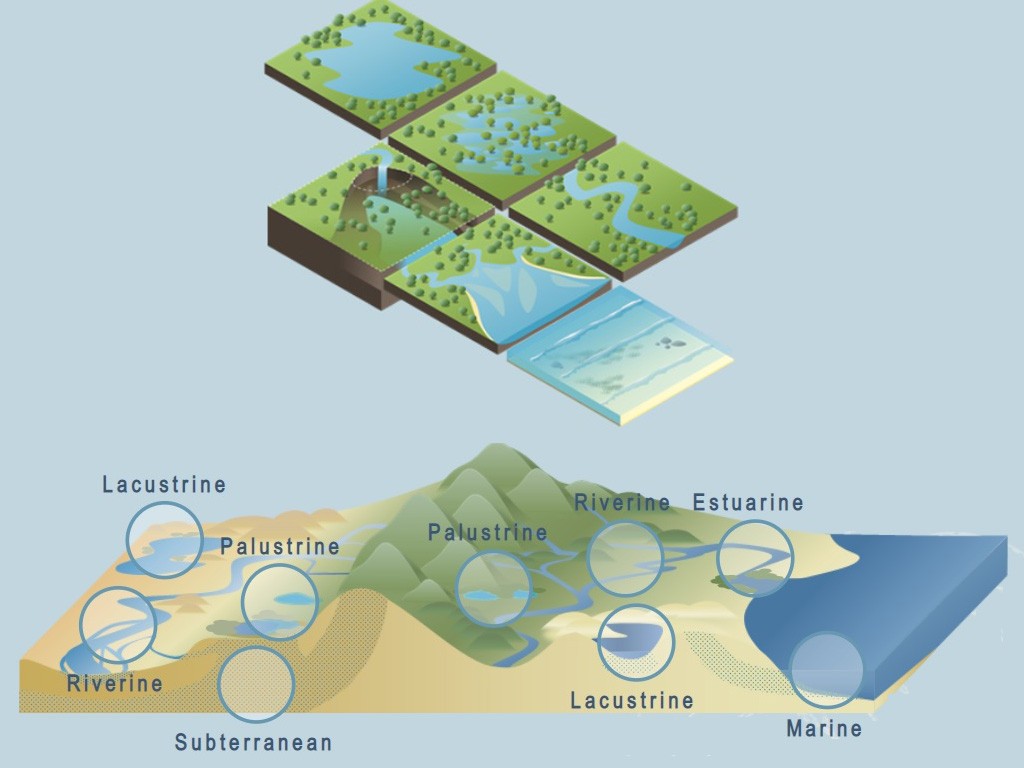

Relationship of different typologies of wetlands with cleaning make sewerage water clean?

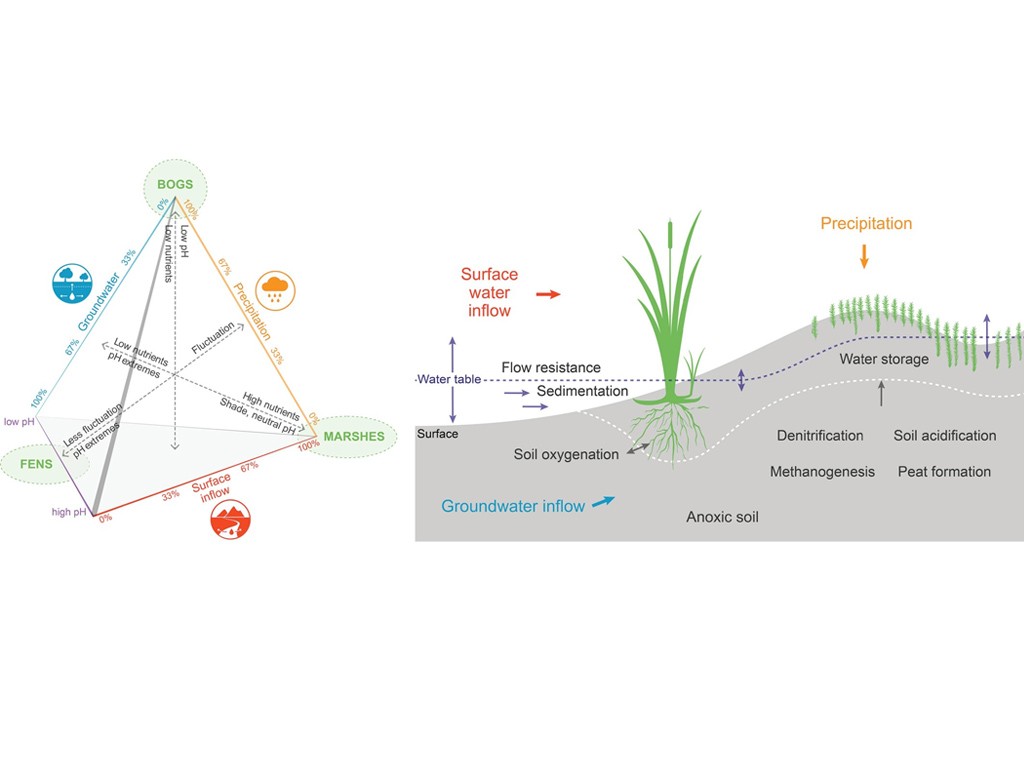

In wetlands, the most important driver is the source of water, which influences the water’s chemical composition and its depth, as well as the frequency and duration of flooding. These hydrological and chemical conditions are also the reasons that the dominant vegetation differs between wetland types. This determines the capacity of a wetland to treat wastewater of different intensities.

1) Natural:

Natural wetlands are characterized by their inherent properties (e.g. anoxia, highly diverse redox conditions, highly organic soils, sometimes extreme pH) and processes (e.g. denitrification, carbon sequestration in peat, methanogenesis) that are uncommon in terrestrial habitats, which makes them an ideal natural laboratory to examine and extend established trait-based theory.

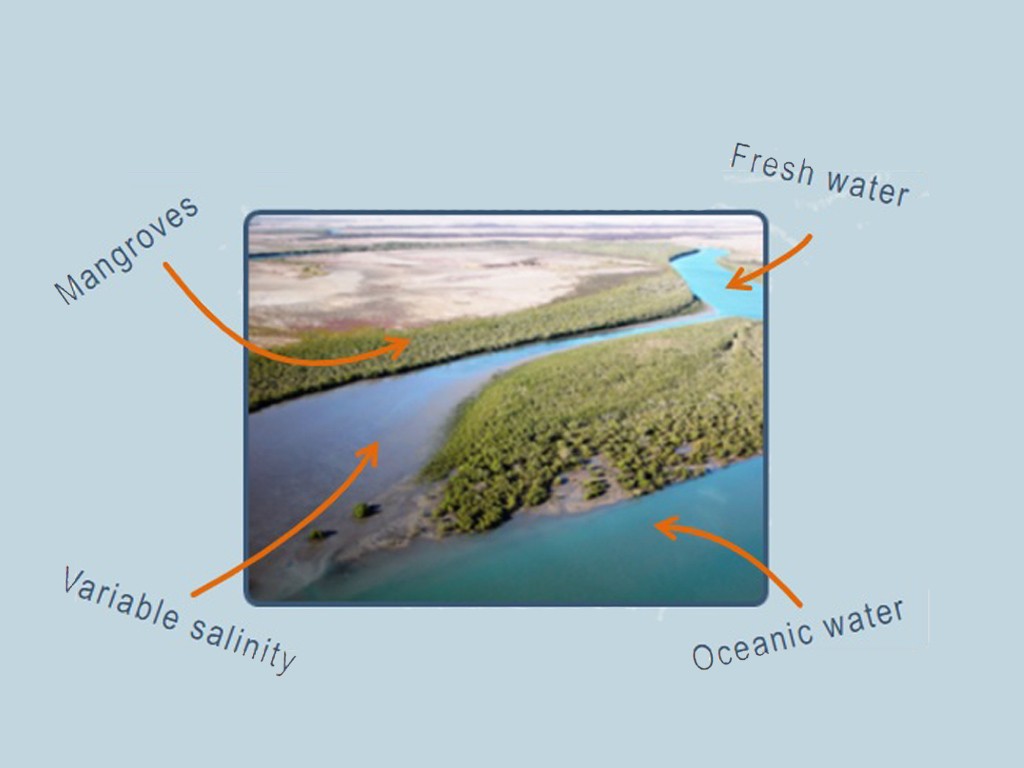

a) Estuarine wetlands (Coastal):

These are the tidal systems that are influenced both by oceanic water and freshwater run-off. These include mangroves and coastal flatlands with dense semi-marine vegetation which host a diverse biological ecosystem that helps in the heavy transfer of nutrients which allows high nitrogen to be broken down to make the water more suitable for groundwater use.

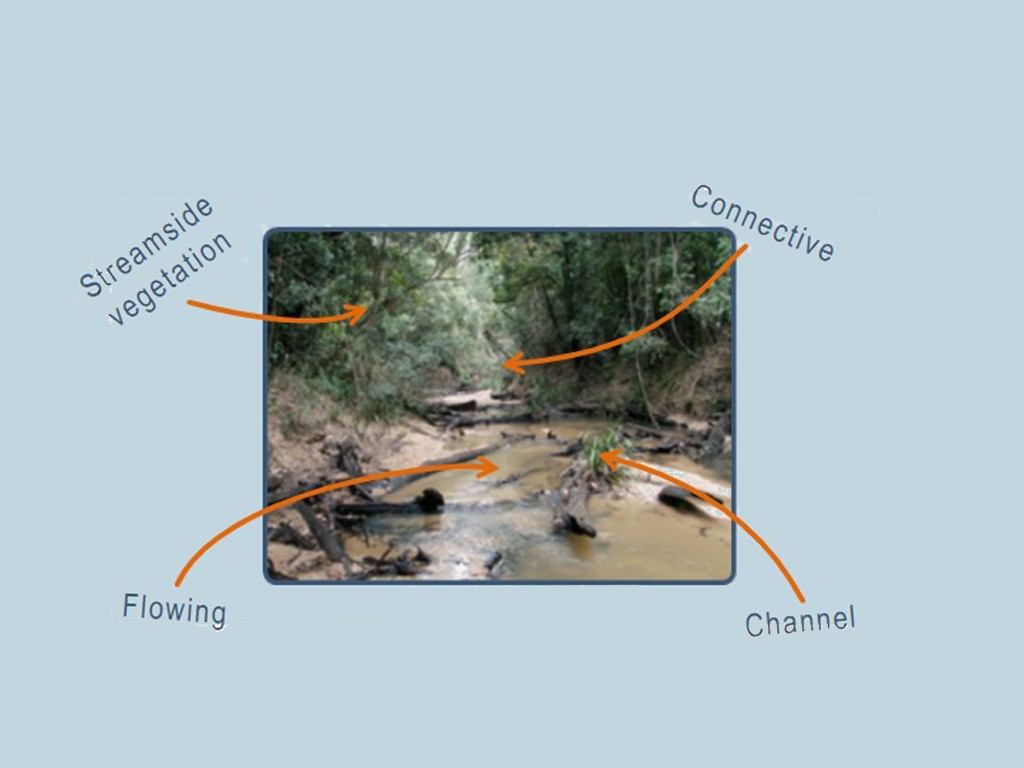

b) Riverine wetlands (Coastal/Inland):

These are the tidal systems of deeper water habitats within a channel moving in a certain direction flow. Here, the direction and the flow of the system determine the extent to which water can be purified. Studies show the presence of pollution attenuation by lowering quantities of nutrients and BOD in the polluted water to purify it to a degree of re-usability (Sileshi, Awoke, Beyene, Stiers, Triest, 2020).

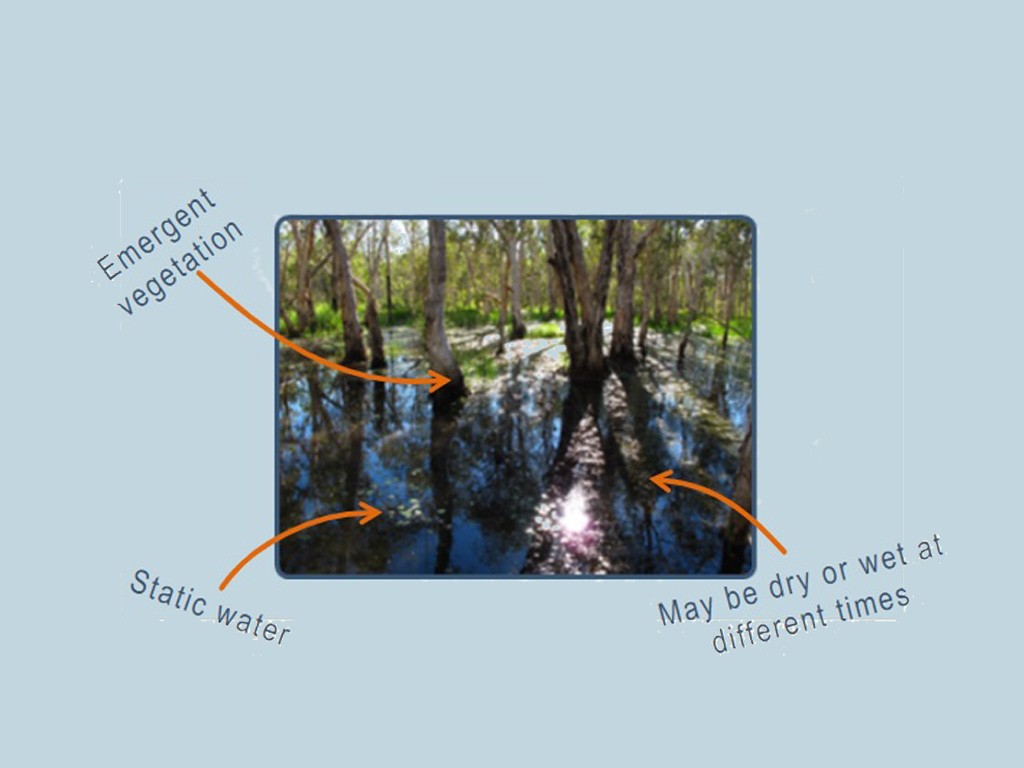

c) Palustrine/Lacustrine wetlands (Coastal/Inland):

These are the tidal systems that are influenced both by oceanic water and freshwater run-off. These include mangroves and coastal flatlands with dense semi-marine vegetations which host a diverse biological ecosystem that helps in the heavy transfer of nutrients which allows high nitrogen to be broken down to make the water more suitable for groundwater use.

d) Fens, Bogs & Marshes (Inland-Freshwater):

Inland freshwater wetlands with sparse or absent tree cover: bog, fen, and marsh are peatlands that offer the water flow regulation including water storage and flood attenuation; (ii) climate regulation in the form of energy exchange, carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions; and (iii) water quality regulation by biogeochemical transformations, retention or removal of excess nutrients from runoff

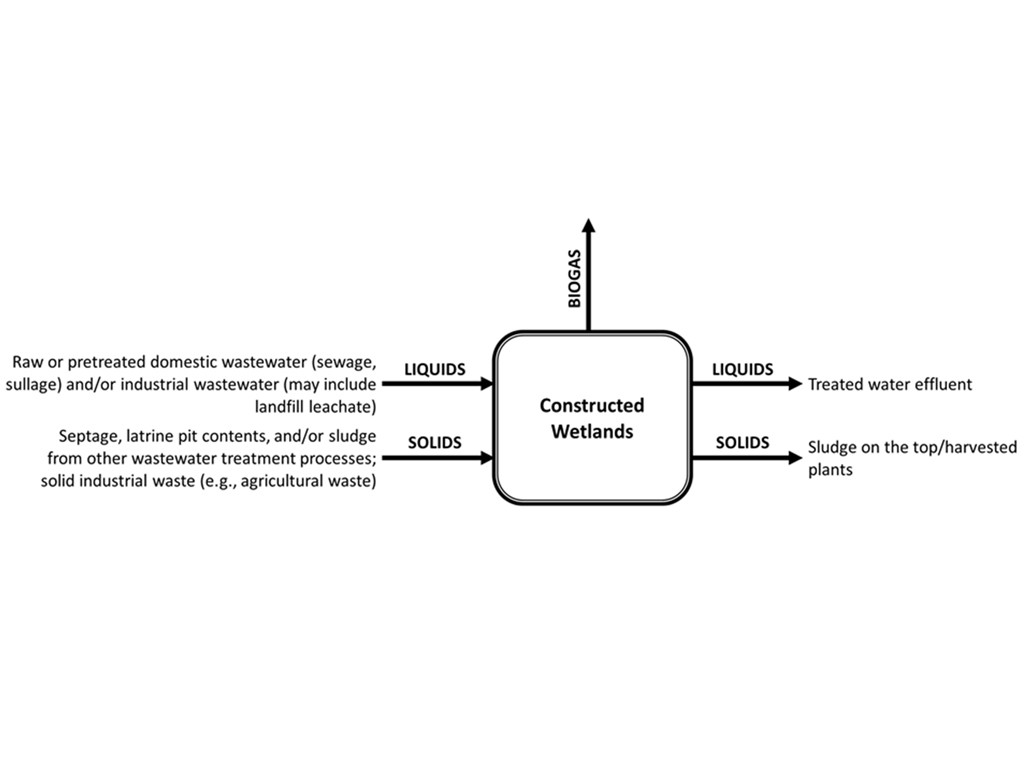

2) Constructed/Man Made:

A constructed wetland is an organic wastewater treatment system that mimics and improves the effectiveness of the processes that help to purify water similar to naturally occurring wetlands. The system uses water, aquatic plants (i.e.: reeds, duckweed), naturally occurring microorganisms and a filter bed (usually of sand, soils, and/or gravel). Constructed wetlands can be used for either secondary or tertiary wastewater treatment. (Centre for Science and Environment, 2022).

a) HYBRID-WETLANDS: Neknampur lake constructed floating treatment wetland:

The FTW is an ingenious bamboo raft with its sides made of thermocol blocks and plastic bottles which are chemically inert. A layer of gunny sacking stretches across the raft’s bottom to create a tray that holds a two-centimeter layer of gravel. Saplings have been planted in the soil with their roots reaching into the water. Another unique feature of the restoration process is the way water hyacinth is used to clean the lake. Water hyacinth is usually seen as a problem because it chokes water bodies and destroys other aquatic life. The lake is also using aerators to oxygenate the water.

b) FREE-WATER-SURFACE WETLAND: Clayton County constructed treatment wetland:

This sewage water management tool accommodates water reclamation, water production, and watershed management. The plan for this project also identifies improvements to be made over the next 20 years (long term), with a focus on the need for watershed protection and stormwater management. Using their innovative water recycling strategy, can reclaim up to 20 million gallons of used water per day. Reclaimed water is stored in reservoirs for eventual reuse as drinking water: the technique is an example of indirect potable reuse through Constructed Treatment Wetlands.

c) SUBSURFACE-BIOTIC WETLANDS: East Kolkata constructed treatment wetlands:

This sewerage water management tool accommodates water reclamation, water production, and watershed management. The plan also identified improvements to be made over the next 20 years, with a focus on the need for watershed protection and stormwater management. Using their innovative water recycling strategy, can reclaim up to 20 million gallons of used water per day. Reclaimed water is stored in reservoirs for eventual reuse as drinking water: the technique is an example of indirect potable reuse. Constructed Treatment Wetlands.

The social aspect of wetland’s relationship with wastewater?

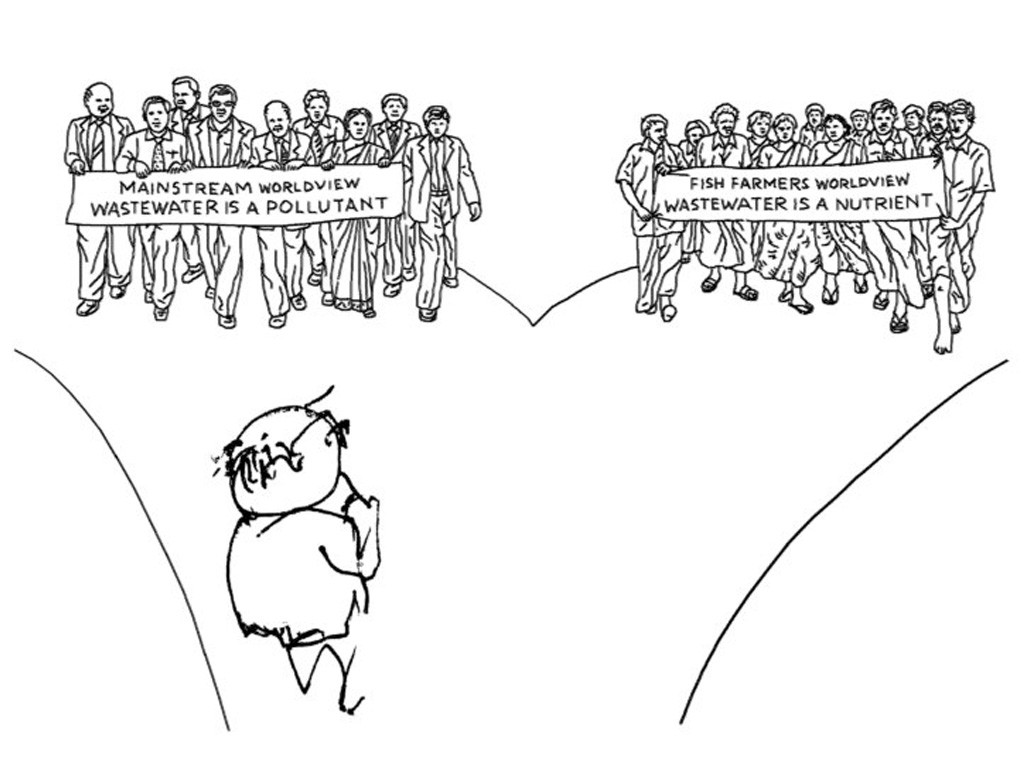

The 2012 Ramsar Convention lists ‘ecosystem services’ as part of the definition of ecological character, including provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural services. In the case of East Kolkata Wetland area, which is one of the few Ramsar sites in India, inhabitants’ lifestyles around it can be divided on the basis of three basic wetland practices: wastewater fisheries, effluent-irrigated paddy cultivation, and vegetable farming on garbage substrate.

The uniqueness of the people living in and around wetlands lie in their capacity to convert, through natural resource management, an ecologically disadvantageous situation into one that offers much better livelihood opportunities. City sewage water area is already successfully being used for farming freshwater fish. Subsequently, a second crop of paddy is grown using pond effluent, a practice that continues, reviving the fortunes of the poorer fish farmers for the next few generations. Thus saving the population from the need to migrate to alien pastures in renewed search for livelihood. The wetlands form a good example of productive commercial activities and support one of the largest clusters of livelihood opportunities for the poorer section of the community.

Wetland then, now what?

Most of the natural and constructed wetland biodiversity and its related ecosystem services in India are being threatened by aggressive urban encroachment. This is primarily because of the lack of sensitive management plans and clear demarcation which leads to a frenzy of building activity around the wetlands on land that was previously designated as “wetlands” but is no longer legally so and has since been taken over for development.

For now, there is hope!

The recent past has seen a lot of initiatives taken on the part of citizens and authorities to treat water in cost effective and natural ways, of which wetlands (both natural and constructed) are strong choices. With the help of diverse types of wetland plants and ingenious techniques (resembling Jugaad), the Indian cities in particular are treating the water in-situ. Drastically improving the quality of water going back to ground or even other purposes. Citizens and NGOs in particular have been on the front end of experimenting and creating new curriculums for study and practice around ‘treatment wetlands’.

About the Author

Anubhav Borgohain is an architect/urban designer working in the field of urban research, specializing in resilience urbanism. He has recently worked on the ‘Rising water, Safer Shores, the BReUCom project with the Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation- ITC University of Twente, focusing on dissemination of urban flooding preparedness through game development. He has recently presented at the International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies (conducted by I.C.O.M.O.S., Austria, Nov. 2021) and in the First International ONLINE conference on Pandemics and Urban Form, PUF2022, April 2022.

Related articles

Remembering Frank O. Gehry: The Architect Who Redrew Skylines

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “